Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Mood Disorders: Bipolar (Manic–Depressive) Disorders

Bipolar (Manic–Depressive) Disorders: Somatotherapy

Somatotherapy

Efficacious Agents for Various Phases of Manic–Depressive Disorder

Over the past 10 years medications have proliferated for the treat-ment

of various phases of the disorder. The clinician must pick through an array of

scientific data and marketing claims in order to choose the appropriate

treatment. Two conceptual approaches help in this task. First, available

scientific data can be reviewed and evaluated according to the techniques of

“evidence-based medicine”.

The second conceptual approach that we have found useful is to propose

an explicit definition for the term “mood stabilizer” and evaluate the role of

various medications against this defini-tion. The US Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) does not for-mally define the term, but it stands to

reason that an agent would be optimally useful for treatment of

manic–depressive disorder if it had efficacy in four roles: 1) treatment of

acute manic symp-toms; 2) treatment of acute depressive symptoms; 3)

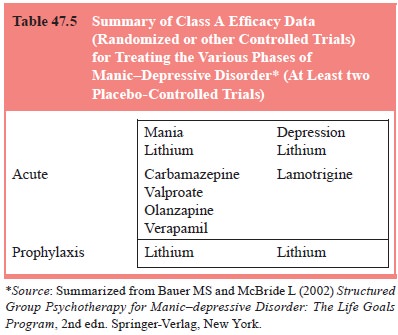

prophylaxis of manic symptoms; and 4) prophylaxis of depressive symptoms Table

47.5 summarizes the findings of this approach.

There are additional Class A controlled trials (nonpla-cebo-controlled)

that support efficacy for multiple older, typi-cal neuroleptics as well as the

benzodiazepines, lorazepam and clonazepam.

In contrast to evidence regarding acute mania, evidence is scarce

concerning efficacy of specific agents for acute

depressive episodes. Most treatment is undertaken primarily by extension

from treatment experience in unipolar depression. In reviewing studies of

agents for the prophylaxis of manic or depressive symptoms, most studies report

recurrence rates without distinguishing between manic and depressive symptoms.

For instance, some studies reported such statistics as time-to-first-episode

without specifying whether the first episode was manic or depressed. Other

studies reported summary statistics for affective symptoms without separating

manic or depressive symptoms. Far and away, the most placebo-controlled support

for any prophylactic agent comes from studies of lithium including studies of

relapse prevention for depression, with support from controlled trials that are

not placebo-controlled for carbamazepine and lamotrigine. The one prophylaxis

study of valproate (Bowden et al.,

2000) showed no difference from placebo (lithium was also found to be no different from placebo in this study, although the

study was under-powered to make definitive conclusions about this comparison).

It may be surprising that, given the paucity of data on treat-ment of

acute depression and prophylaxis of manic–depressive disorder, frequently many

other medications are used chroni-cally in this illness, sometimes as

first-time agents, for instance, valproate or carbamazepine. Although

neuroleptics have acute anti-manic evidence, despite the fact that there is

little evidence for prophylactic efficacy, they are often used chronically. This

is because these agents are typically started during the course of an acute

manic episode and clinicians are reluctant to stop them and switch to a

different agent such as lithium. In addition, many individuals have failed or

have been intolerant of treatment with lithium and they are therefore treated

using the “next best thing”. This is not necessarily suboptimal treatment.

However, it is important that the clinician recognize that data on long-term

prophylactic efficacy is quite scanty for these agents, as it is for many other

agents used in psychiatric practice.

Several additional issues in prophylaxis of manic–depres-sive disorder

deserve comment. First, when is lifetime, or at least long-term, prophylaxis

warranted? After one manic episode? One hypomanic episode? One depressive

episode with a strong fam-ily history of manic–depressive disorder? There is

insufficient empirical evidence with which to make strong recommendations. In

clinical practice without clear guidelines, such decisions need to take into

account the capability of the patient and family inreporting symptoms, rapidity

of onset of episodes, episode se-verity and associated morbidity. Clearly, the

risks of a wait-and-see strategy would be different in a person who had a

psychotic manic episode than in a person who had mild hypomania.

Secondly, can lithium ever be discontinued? Again, there are no solid

data on which to base this decision. However, if lith-ium discontinuation is

contemplated, there is evidence that rapid discontinuation (in less than 2

weeks) is more likely to result in relapse than slow taper (2–4 weeks), with

relapse rates higher in type I than in type II patients. In type I patients,

relapse rates for rapid discontinuation versus slow taper were, respectively,

96 and 73%, whereas in type II patients they were 91 and 33% (Faedda et al., 1993).

Thirdly, a set sequence of treatment for refractory manic– depressive

disorder has yet to be established. In particular, persons with rapid cycling

represent a treatment dilemma. Although anti-depressants may induce rapid

cycling, they often leave the person in a protracted, severe depression.

Switching from one antimanic agent to another often results in resumption of

cycling. Complex treatment strategies may be required, such as anticonvulsants

plus lithium, combinations of anticonvulsants, or adjuvant treat-ment with high

doses of the thyroid hormone thyroxine.

A Simple Treatment Algorithm for Manic–Depressive Disorder

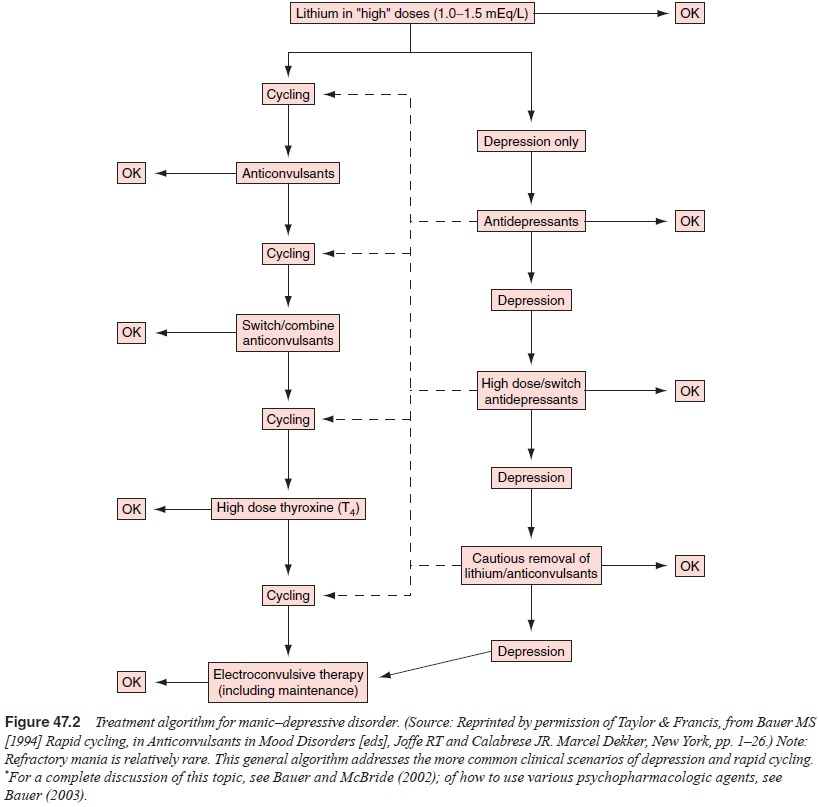

A treatment algorithm for refractory manic–depressive disor-der,

including strategies to deal with rapid cycling is found in Figure 47.2. It is

derived from clinical practice guidelines from the US Veterans Administration

and, by design, primarily speci-fies drug classes rather than individual

agents. The entry point for this algorithm is the occurrence of any major mood

episode (depression, hypomania, mania, or mixed episode) in an unmedi-cated

patient. Patients with recurrence on medications may enter the algorithm at the

appropriate point along the flow diagram. For simplicity of presentation, only

depressive and cycling outcomes are illustrated. This is because depressive

episodes are more common than manic or hypomanic episodes, and all but the most

refractory of the latter episodes are relatively easily treated by the addition

(or resumption) of lithium or anticonvulsants or the use of neuroleptics, as

summarized above.

Balancing Beneficial and Unwanted Effects of Medications

All psychotropic medications have side effects. Some are actu-ally

desirable (e.g., sedation with some antidepressants in per-sons with prominent

insomnia), and specific medications are often chosen on the basis of desired

side effects. However, side effects usually represent factors that decrease a

patient’s quality of life and compromise compliance. Reviews of side effects of

antidepressants and neuroleptics can be found on depression and schizophrenia,

respectively. It should be recalled in regard to antidepressants, however, that

all can cause rapid cycling and mixed states in persons with manic–depressive

dis-order. These effects are not uncommonly encountered in clinical practice

and should be watched for, even in persons taking mood-stabilizing agents.

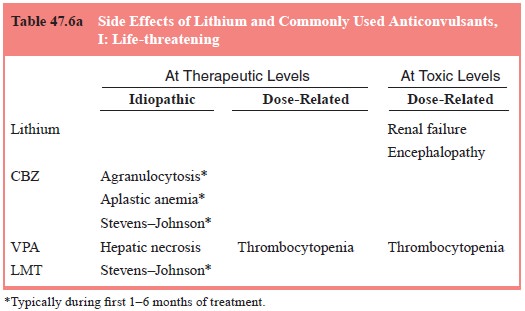

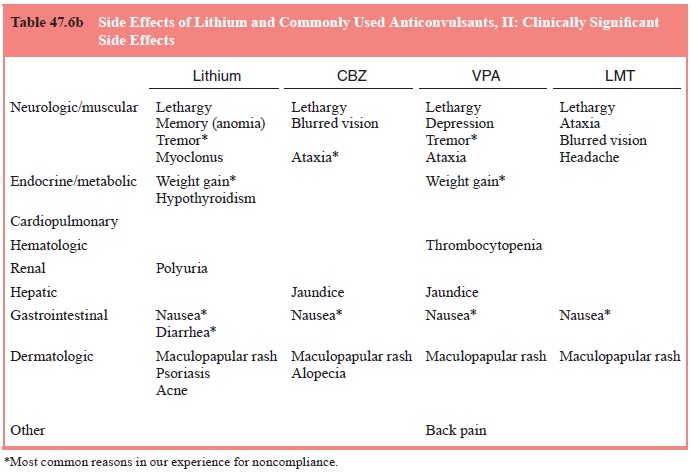

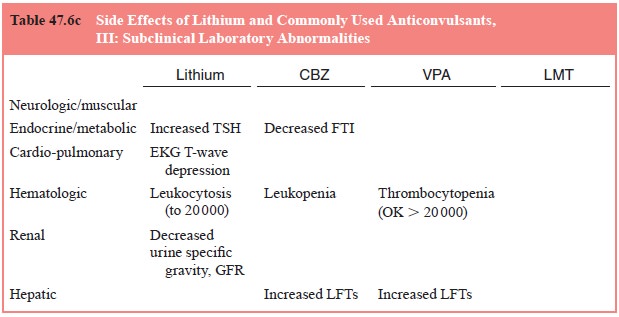

A brief overview of the most frequent or important side effects of

lithium, carbamazepine and valproic acid can be found in Table 47.6a–c. Note

that some side effects may be encountered at any serum level of the drug, even

within the therapeutic range. Some side effects may be dose-related even within

that range and

may respond to dosage reduction. Others are more idiosyncratic and may

need other management, as detailed in a subsequent sec-tion. Note that not all

laboratory findings represent pathological processes that are associated with

or presage morbidity for the patient; that is, not all are clinically

significant.

Note also that the concept of the “therapeutic level” is not

straightforward. The lower limit is usually established by the lowest level

necessary for therapeutic effect, whereas the up-per limit is set by the lowest

level associated with regular, sig-nificant toxicity. This range is never

established with complete precision. For some medications such as lithium, the therapeutic

window is actually quite narrow, with toxic effects developing with some

regularity after the upper limit of the therapeutic range is surpassed and with

serious toxicity developing at only mod-estly higher serum levels. As a further

complication, for many persons the minimum level of lithium for good response

may be substantially above the 0.5 to 0.8 mEq/L that is usually set as the

lower therapeutic limit, but this is reached only at the cost of increased

incidence of side effects. On the other hand, experi-ence with valproic acid,

the upper limit of the therapeutic range for mood stabilization may actually be

125 mg/dL rather than the listed range of 100 mg/dL usually accepted for

antiepileptic effect, and this level may be reached without undue side effects.

Thus, established therapeutic levels should be used as important guidelines,

and therapeutic levels should only be exceeded with careful monitoring.

However, one must not be falsely reassured that reaching the lower level of a

therapeutic range is equally ef-fective for all patients, while taking with a

grain of salt the upper limits of the therapeutic range in drugs with a wider

therapeutic window.

Another important issue to consider is drug–drug interac-tions, which

may lead to side effects. Such interactions are often associated with increases

in serum levels of the drug of interest. For example, addition of thiazide

diuretics, or nonsteroidal an-tiinflammatory agents, the latter available over

the counter, is a common reason for increase in lithium level and development

of toxicity. However, at other times the drug–drug interactions may not be

reflected in an increased serum level if the main interac-tion is displacement

of protein-bound drug. Because free drug concentrations are usually 1 to 10% of

total serum drug, a dis-placement of even 50% of bound drug may be associated

with negligible if any changes in total serum level. However, since both

therapeutic and toxic effects are due to free, not bound, drug, unwanted side

effects may develop despite total drug levels measured in the therapeutic

range.

Guiding Principles of Managing Side Effects

Although some side effects may be desirable, in many cases they are

impediments to treatment, frequently of sufficient importance to lead to noncompliance.

Clinicians might reframe the noncom-pliance issue more appropriately as

“insufficient provider–patient cost–benefit analysis”. Stressing compliance

when a person suf-fers from significant side effects is usually much less

effective than working to set appropriate expectations of the patient and to

find a regimen of minimal toxicity. Managing side effects is as much

psychotherapeutic as medical.

There are several strategies available to improve patients’ tolerance of

medications. First, dose reduction may be achieved without compromising

efficacy in some patients. Some side ef-fects, such as lithium-induced nausea,

usually respond well to this, whereas others, such as lithium-induced memory

loss, im-prove less reliably. Secondly, simple changes in preparation may be

helpful, such as using enteric-coated lithium. Uncoated valp-roic acid causes

nausea so frequently that only the coated forms are routinely used; however,

the pediatric “sprinkle” preparation may be of some benefit in persons with nausea

even with enteric-coated valproic acid. Thirdly, changing the administration

sched-ule may ameliorate side effects. Commonsense strategies such as taking

nausea-inducing medications after a meal should not be overlooked. Single daily

dosing of lithium, carbamazepine, or valproic acid may decrease daytime

sedation without compro-mising efficacy. For more obscure reasons, single daily

dosing of lithium appears to decrease polyuria quite effectively.

Fourthly, addition of medications to counteract side effects can

sometimes be the only way to continue treatment. Addition of beta-blockers can

reduce lithium- or valproic acid-induced tremors. Judicious use of thiazide

diuretics, often in conjunction with potassium-sparing diuretics or potassium

supplements, can reduce lithium-induced polyuria. Finally, change to another

drug may be the only alternative. This is clearly indicated in the case of

serious allergic reactions. Polypharmacy should be avoided wherever possible.

Psychotherapies

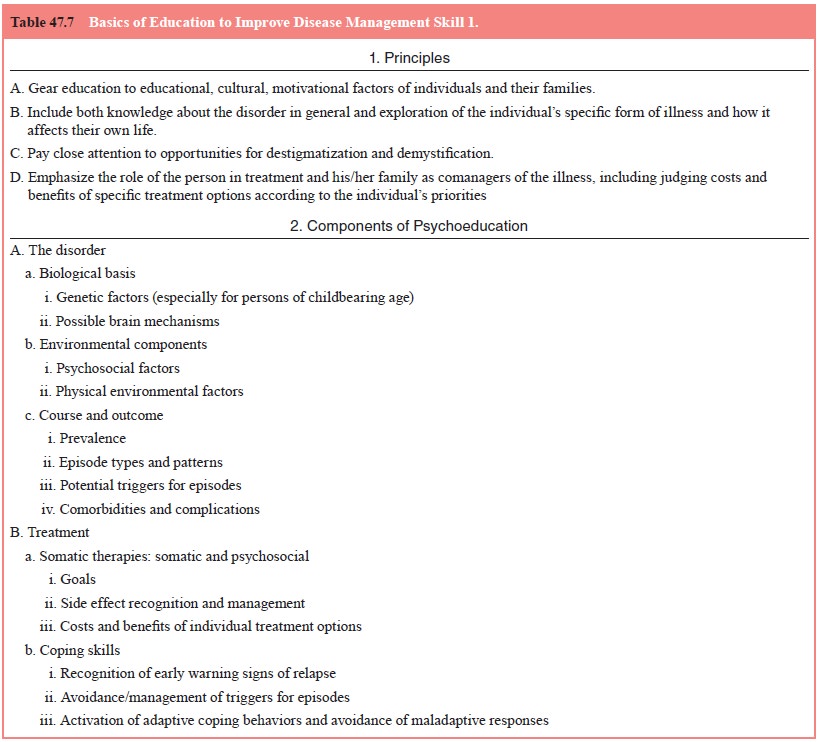

It is important to note that psychotherapy has been studied almost

exclusively in the context of ongoing medication management, rather than as a

substitute for, or alternative to, medication treat-ment. Rather, psychotherapy

has been utilized as an adjuvanttreatment to optimize outcome in the illness.

Psychotherapy has been viewed as having one or more of several roles in the

man-agement of the disorder.

Recall that both somatic therapies and psychotherapies to date have been

predominantly oriented toward improving clinical outcome. Under this

conceptualization psychotherapy has been thought directly to address symptoms,

such as cognitive therapy for depressive symptoms. Less frequently has

psychotherapy been developed with an explicit component geared toward

addressing the functional deficits in manic–depressive disorder. However,

functional outcome has often been measured in formal trials of various types of

psychotherapy. A third conceptualization has been to use psychotherapy as a

predominantly educative method to assist patients in participating more

effectively in treatment. In this latter regard, treatment is geared toward

improving “host factors”, that is, those factors not directly due to the

disease but that have an impact on its course or treatment, through education,

support and problem solving. Such host factors include illness management

skills, which may be improved through psychoedu-cation and attention to

building the therapeutic alliance. Basics of education are summarized in Table

47.7.

An evidence-based review similar to that for somatother-apy has recently

been carried out for psychotherapeutic inter-ventions. Bauer and McBride (2002)

identified five main types of psychotherapy that have been studied in

manic–depressive disorder: couples–partners, group interpersonal or

psychoeduca-tive, cognitive–behavioral, family, and interpersonal and

social-rhythms. Couples–partners, cognitive–behavioral and family methods all

have some Class A data supporting a role in improv-ing clinical outcome or

functional outcome or the intermediate outcome variable of improving illness

management skills. An ad-ditional finding in this review is the degree of

convergent validity across interventions regarding agenda for disease

management information and skills to be imparted. Specifically, imparting

education, focusing on early warning symptoms and triggers of episodes, and

developing detailed and patient-specific action plans are found across most of

the other interventions as well. For instance, this core agenda is also an important

part of such diverse approaches as the cognitive–behavioral interventions of

Palmer and Williams (1995) and Lam and coworkers (2000); the psychoeducational

interventions of Bauer and coworkers (1998), Perry and coworkers (1999) and

Weiss and coworkers (2000); the interpersonal and social rhythms therapy

(IPSRT) intervention of Frank and coworkers (1999); and the family intervention

of Miklowitz and coworkers (1999). Thus, given the positive results most of

these interventions with explicit disease management components (i.e., patient

education, collaborative management strategies with the patient, inclusion of

as wide a social support system as is available) have produced, it is likely

that this basic approach will be critical. It will perhaps be more critical

even than the specific type of intervention in which these disease man-agement

components are embedded

Related Topics