by Jules Verne | Supplementary/Story - A day in 2889 of an American Journalist | 10th English: UNIT 5 : Supplementary/Story: A day in 2889 of an American Journalist

Chapter: 10th English: UNIT 5 : Supplementary/Story: A day in 2889 of an American Journalist

A day in 2889 of an American Journalist

Supplementary

A day in 2889 of an American Journalist

Jules Verne

This story speaks about the people of the twenty-ninth century

who live in fairyland. Surfeited as they are with marvels, they are indifferent

to the presence of each new marvel. To them all seem natural.

The year is 2889, the date 25th July and the place is the office

block of the Managing Editor of the Earth Herald, the world’s largest

newspaper.

In this futuristic story written in 1889, the writer describes how

he visualizes the world a thousand years later – a world of technological

advancements where newspapers are not printed but ‘spoken’.

Read the following excerpt for a glimpse of this future world.

That morning Francis Bennett awoke in rather a bad temper. This

was eight days since his wife had been in France and he was feeling a little

lonely. As soon as he awoke, Francis Bennett switched on his phonotelephote whose wires led to the house he owned in the Champs-Elysees.

The telephone, completed by the telephote, is another of our

time’s conquests! Though the transmission of speech by the electric current was

already very old, it was only since yesterday that vision could also be

transmitted. A valuable discovery, and Francis Bennett was by no means the only

one to bless its inventor when, in spite of the enormous distance between them,

he saw his wife appear in the telephotic mirror. ‘Francis … dear Francis!...’

His name, spoken by that sweet voice, gave a happier turn to

Francis Bennett’s mood. He quickly jumped out of bed and went into his

mechanized dressing room. Two minutes later, without needing the help of a valet, the machine deposited

him, washed, shaved, shod, dressed and buttoned from top to toe, on the

threshold of his office. The day’s work was going to begin.

Francis Bennett went on into the reporters’ room. His fifteen

hundred reporters, placed before an equal number of telephones, were passing on

to subscribers the news which had come in during the night from the four

quarters of the earth. In addition to his telephone, each reporter has in front

of him a series of commutators, which allow him to get into communication with this or that

telephotic line.

Thus the subscribers have not only the story but the sight of

these events.

Francis Bennett questioned one of the ten astronomical reporters –

a service which was growing because of the recent discoveries in the stellar

world.

‘Well, Cash, what have you got?’

‘Phototelegrams from Mercury, Venus and Mars, Sir.’

‘Interesting! And Jupiter?’

‘Nothing so far! We haven’t been able to understand the signals

the Jovians make. Perhaps ours haven’t reached them? ….’

‘Aren’t you getting some result from the moon, at any rate?’

‘Not yet, Mr Bennett.’

‘Well, this time, you can’t blame optical science! The moon is six

hundred times nearer than Mars, and yet our correspondence service is in

regular operation with Mars. It can’t be telescopes we need…’

‘No, it’s the inhabitants,’ Corley replied.

‘You dare tell me that the moon is uninhabited?’

‘On the face it turns towards us, at any rate, Mr Bennett. Who

knows whether on the other side…’

‘Well, there’s a very simple method of finding out.’

‘And that is?’

‘To turn the moon round!’

And that very day, the scientists of the Bennett factory started

working out some mechanical means of turning our satellite right round.

On the whole, Francis Bennett had reason to be satisfied. One of

the Earth Herald’s astronomers had just determined the elements of the new

planet Gandini. It is at a distance of 12,841,348,284,623 metres and 7

decimetres that this planet describes its orbit round the sun in 572 years, 194

days, 12 hours, 43 minutes, 9.8 seconds. Francis Bennett was delighted with

such precision.

‘Good!’ he exclaimed. ‘Hurry up and tell the reportage service

about it. You know what a passion the public has for these astronomical

questions. I’m anxious for the news to appear in today’s issue!’

The next room, a broad gallery about a quarter of a mile long, was

devoted to publicity, and it well may be imagined what the publicity for such a

journal as the Earth Herald had to be. It brought in a daily average of three

million dollars. They are gigantic signs reflected on the clouds, so large that

they can be seen all over a whole country. From that gallery a thousand

projectors were unceasingly employed in sending to the clouds, on which they

were reproduced in colour, these inordinate advertisements.

At that moment the clock struck twelve. The director of the Earth

Herald left the hall and sat down in a rolling armchair. In a few minutes he

had reached his dining room half a mile away, at the far end of the office.

The table was laid and he took his place at it. Within reach of

his hand was placed a series of taps and before him was the curved surface of a

phonotelephote, on which appeared the dining room of his home in Paris. Mr and

Mrs Bennett had arranged to have lunch at the same time – nothing could be more

pleasant than to be face to face in spite of the distance, to see one another

and talk by means of the phonotelephotic apparatus.

Like everybody else in easy circumstances nowadays, Francis

Bennett, having abandoned domestic cooking, is one of the subscribers to the

Society for Supplying Food to the Home, which distributes dishes of a thousand

types through a network of pneumatic tubes. This system is expensive, no doubt,

but the cooking is better. So, not without some regret, Francis Bennett was

lunching in solitude. He was finishing his coffee when Mrs Bennett, having got

back home, appeared in the telephote screen.

When he had finished his lunch, he went across to the window,

where his aero-car was waiting.

‘Where are we going, Sir?’ asked the aero-coachman. ‘Let’s see.

I’ve got time…’ Francis Bennett replied. ‘Take me to my accumulator works at

Niagara.’

The aero-car shot across space at a speed of about four hundred

miles an hour. Below him were spread out the towns with their moving pavements

which carry the wayfarers along the streets, and the countryside, covered, as

though by an immense spider’s web, by the network of electric wires.

Within half an hour, Francis Bennett had reached his works at

Niagara, where, after using the force of the cataracts to produce energy, he

sold or hired it out to the consumers. Then he returned, by way of

Philadelphia, Boston and New York, to Centropolis, where his aero-car put him

down about five o’clock.

The waiting-room of the Earth Herald was crowded. A careful

lookout was being kept for Francis Bennett to return for the daily audience he

gave to his petitioners. Among their different proposals he had to make a

choice, reject the bad ones, look into the doubtful ones, and welcome the good

ones.

He soon got rid of those who had only useless or impracticable

schemes. A few of the others received a better welcome, and foremost among them

was a young man whose broad brow indicated a high degree of intelligence.

‘Sir’, he began, ‘though the number of elements used to be

estimated at seventy-five, it has now been reduced to three, as no doubt you

are aware?’

‘Perfectly,’ Francis Bennett replied.

‘Well, Sir, I’m on the point of reducing the three to one. If I

don’t run out of money I’ll have succeeded in three weeks.’

‘And then?’

‘Then, Sir, I shall really have discovered the absolute’.

‘And the results of that discovery?’

‘It will be to make the creation of all forms of matter easy –

stone, wood, metal, fibrin ….’

‘Are you saying you’re going to be able to construct a human

being?’

‘Complete… The only thing missing will be the soul!’

Francis Bennett assigned the young fellow to the scientific

editorial department of his journal.

A second inventor, using as a basis some old experiments that

dated from the 19th century, had the idea of moving a whole city in a single

block. He suggested, as a demonstration, the town of Saaf, situated fifteen

miles from the sea; after conveying it on rails down to the shore, he would

transform it into a seaside resort. Francis Bennett, attracted by this project,

agreed to take a half-share in it.

The proposals heard and dealt with, Francis Bennett went to

stretch himself out in an easy-chair in the audition-room. Then, pressing a

button, he was put into communication with the Central Concert. After so busy a

day, what charm he found in the works of our greatest masters, based on a

series of delicious harmonico-algebraic formulae! During his meal, phonotelephotic

communication had been set up with Paris.

‘When do you expect to get back to Centropolis, dear Edith?’ asked

Francis Bennett.

‘I’m going to start this moment’.

‘By tube or aero-train?’

‘By tube’.

‘Then you’ll be here?’

‘At eleven fifty-nine this evening’.

‘Paris time?’

‘No, no! … Centropolis time’.

‘Goodbye then, and above all don’t miss the tube!’

These submarine tubes, by which one travels from Paris in two

hundred and ninety-five minutes, are certainly much preferable to the

aero-trains, which only manage six hundred miles an hour.

Francis Bennett, very tired after so very full a day, decided to

take a bath before going to bed. There was always a bath already in the office.

He touched the button. A rumbling sound began, got louder, increased … Then one

of the doors opened and the bath appeared, gliding along on its rails …

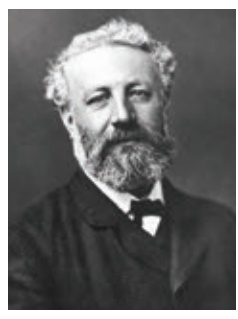

About the author

Jules Verne (1828–1905) was a French poet, playwright and novelist but he earns his place on this list of great

writers because of his futuristic

adventure novels. He has been called the father of science fiction and

has had an incalculable influence on the phototelegrams (n): a telegraphic

development of science fiction writing. More interesting, perhaps, is his place

as a prophet or predictor of technology which wasn’t to be invented until long

after his death. He put a man on the moon, including its launch from a Florida

launchpad to its splashdown in the Pacific; in 1863 he predicted the internet:

Paris in the 20th Century (1863) depicts the details of modern life:

skyscrapers, television, Maglev trains, computers, and a culture preoccupied

with the Internet.

Related Topics