Chapter: The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution, and Ecology: Fishes as social animals: aggregation, aggression, and cooperation

Territoriality - Agonistic interactions of Fishes

Territoriality

Territoriality implies a defended space, either the personal space around an individual (=individual distance) or a bounded area around some resource (e.g., Grant 1997). A territory may encompass several resources, as in male pomacentrid damselfishes in which the territory provides food (algae), a spawning site and the eggs spawned there, and refuge holes from predators where the territory holder also rests at night. Territories are often subunits of the larger home range occupied by an individual (see next section).

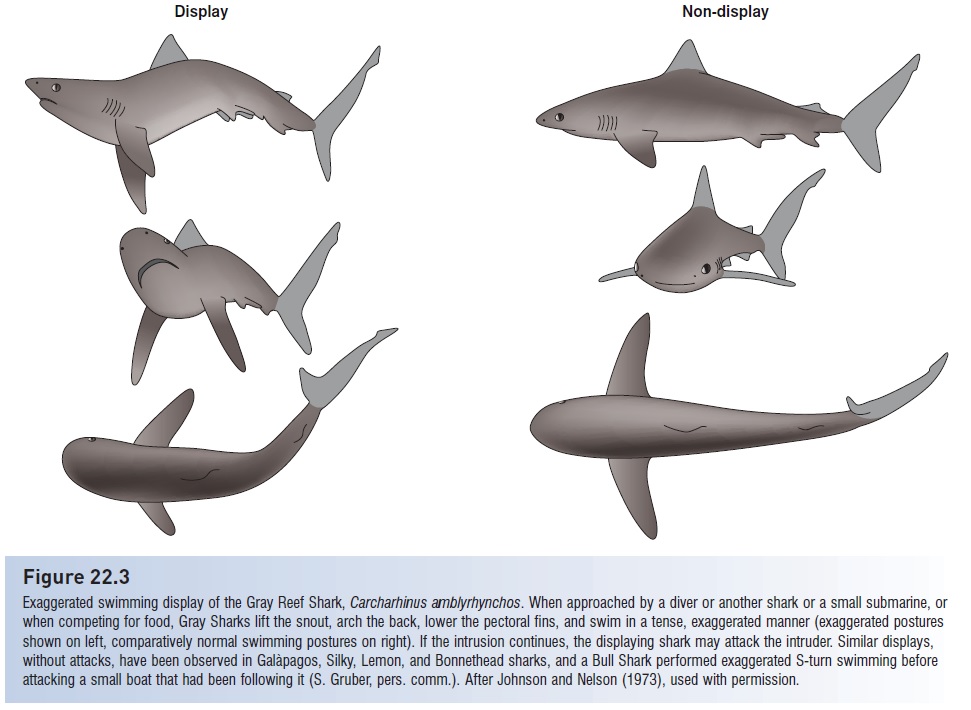

Territoriality is widespread in fishes, occurring in such diverse groups as anguillid eels, cyprinids, ictalurid catfishes, gymnotid knifefishes, salmonids (affecting stocking programs and the effects of introduced species), frogfishes, sticklebacks, pupfishes, rockfishes, sculpins, sunfishes and black basses, butterfl yfishes, cichlids, damselfishes, wrasses barracuda, blennies, gobies, surgeonfishes, and anabantids. Territoriality has not been observed in agnathans or elasmobranchs, although the threat responses of Gray Reef Sharks (see Fig. 22.3) may represent defense of personal space. Territorial defense often involves displays such as fin and gill spreading, lateral displays and exaggerated swimming in place, vocalizations, chasing, and finally biting. Prolonged exchanges of displays frequently occur at territorial boundaries. When territories are being established or contested (as opposed to temporary trespassing), priority of ownership, previous experience, and individual size usually determine the outcome of a dispute. Again, territory holders win over intruders, previous winners defeat previous losers, and large fish win over small fish. Territories near one another can create “territorial mosaics” of several contiguous territories (e.g., salmonids, pomacentrids, mudskippers, blennies; Keenleyside 1979).

The costs of territorial defense – energy and time expended, exposure to predators, resource loss to competitors while defending distant portions of a territory – increase with increasing territory size. Food production affects territory size because a territorial animal must often meet its daily energy requirements from the resources available within its territory. As would be expected, increased food density leads to a decrease in territory size (e.g., in Rainbow Trout; rockfishes, Scorpaenidae; surfperch, Embiotocidae; several damselfishes; Hixon 1980a, 1980b). Interestingly, in Beau Gregory Damselfish, males decrease territory size with increasing food but females respond by increasing territory size. Larger females can produce more eggs and hence increased energy intake apparently overcomes the costs of defending a larger territory (Ebersole 1980).

Territoriality is often flexible. Territorial boundaries and intensity of defense can vary as a function of the relative impacts of different intruders. Herbivorous damselfishes defend a larger space against large competitors such as parrotfishes and surgeonfishes than against small damselfishes; damselfishes also tolerate large competitors for shorter times inside the territory, attacking them more aggressively. The strongest attacks are directed at potential egg predators, which have the greatest relative impact on the reproductive success of the damselfish. Juvenile Coho Salmon also defend a larger territory against larger conspecific intruders. Butterfl yfishes chase species with which they overlap in diet but tolerate the presence of non-competitors (Myrberg & Thresher 1974; Reese 1975; Ebersole 1977; Dill 1978).

Territoriality may also vary over time at several levels. Juvenile grunts (Haemulidae) form daytime resting shoals over coral heads. Individuals stake out small territories of about 0.04 m2 within the shoal; the territories often contain refuge sites from predators. These territories are defended vigorously with open mouth displays, chases, and biting. In the evening, the shoal becomes a polarized school that moves from the reef to adjacent grassbeds to feed. No agonism is seen during the migratory period, as such behavior would negate the antipredator function of the school when moving across the dangerous reef edge. Once in the grassbeds, the shoals break up and the fish occur as widely spaced, foraging individuals, implying space-enforcing behaviors (McFarland & Hillis 1982). Territoriality changes with age in many species. Young Atlantic Salmon are territorial in streams. As they grow and their food requirements shift to larger prey, they move into deeper water and join foraging groups that have dominance hierarchies rather than territories (Wankowski & Thorpe 1979). In some species, agonistic interactions occur during the breeding season, with fish aggregating peaceably at other times (e.g., codfishes).

Related Topics