Chapter: Essential Microbiology: Microbial Diversity

A few words about Microbial Classification

Microbial Diversity

A few words about classification

In this section, we examine the wide diversity of microbial life. We shall discuss major structural and functional characteristics, and outline the main taxonomic divisions within each group. We shall also consider some specific examples, particularly with respect to their effect on humans. By way of introduction, however, we need to say something on the subject of the classification of microorganisms.

In any discussion on biological classification, it is impossible to avoid mentioning Lin-naeus, the Swedish botanist who attempted to bring order to the naming of living things by giving each type a Latin name. He even gave himself one – his real name was Carl von Linne!´ It was Linnaeus who was responsible for introducing the binomialsystem of nomenclature, by which each organism was assigned a genus and a species. To give a few familiar examples, you and I are Homo sapiens, the fruit fly that has contributed so much to our understanding of genetics is Drosophila melanogaster, and, in the mi-crobial world, the bacterium responsible for causing anthrax is Bacillus anthracis. Note the following conventions, which apply to the naming of all living things (the naming of viruses is something of a special case):

· the generic (genus) name is always given a capital letter

· the specific (species) name is given a small letter

· the generic and specific name are italicised, or, if this isn’t possible, underlined

The science of taxonomy involves not just naming or-ganisms, but grouping them with other organisms that share common properties. In the early days, classifica-tion appeared relatively straightforward, with all living things apparently fitting into one of two kingdoms. To oversimplify the matter, if it ran around, it was an an-imal, if it was green and didn’t, it was a plant! As our awareness of the microbial world developed, however, itwas clear that such a scheme was not satisfactory to accommodate all life forms, and in the mid-19th century, Ernst Haeckel proposed a third kingdom, the Protista, to include the bacteria, fungi, protozoans and algae.

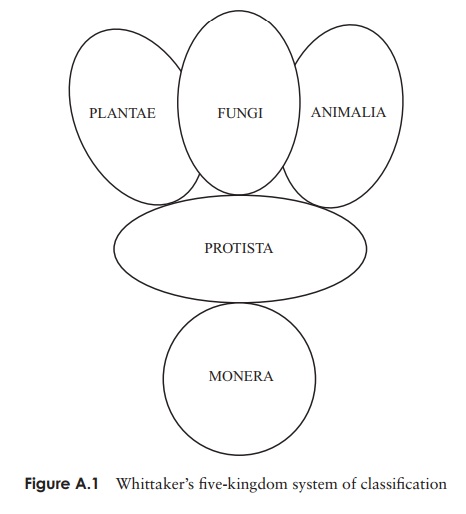

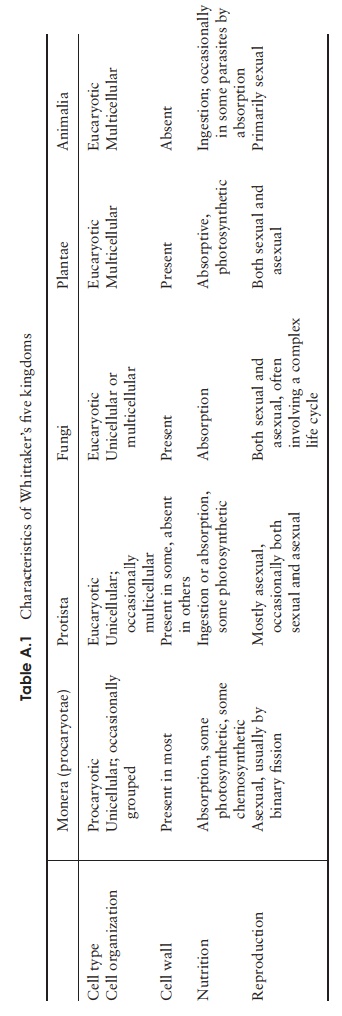

In the 20th century, an increased focus on the cellular and molecular similarities and dissimilarities between organisms led to proposals for further refinements to the three-kingdom system. One of the most widely accepted of these has been the five-kingdom system proposed by Robert Whittaker in 1969 (Figure A1). Like some of itspredecessors, this took into account the fundamental difference in cell structure between procaryotes and eucaryotes, and so placed procaryotes (bacteria) in their own kingdom, the Monera, separate from single-celled eucaryotes. Another feature of Whittaker’s scheme was to assign the Fungi to their own kingdom, largely on account of their distinctive mode of nutrition. Table A1 shows some of the characteristic features of each kingdom.

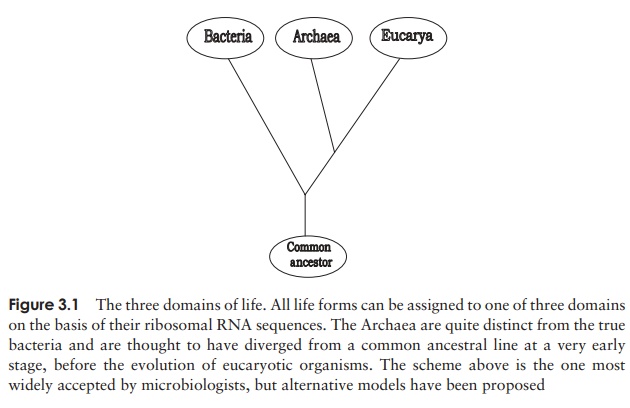

Molecular studies in the 1970s revealed that the Archaea differed from all other bac-teria in their 16S rRNA sequences, as well as in their cell wall structure, membrane lipids

and aspects of protein synthesis. These differences were seen as sufficiently important for the recognition of a third basic cell type to add to the procaryotes and eucaryotes. This led to the proposal of a three-domain scheme of classification, in which procary-otes are divided into the Archaea and the Bacteria (Figure 3.1). The third domain, the Eucarya represents all eucaryotic organisms. The domains thus represent a level of clas-sification that goes even higher than the kingdoms. Although the Archaea (the word means ‘ancient’) represent a more primitive bacterial form than the Bacteria, they are in certain respects more closely related to the eucaryotes, causing biologists to revise their ideas about the evolution of the eucaryotic state.

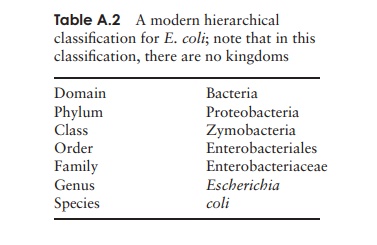

In hierarchical systems of classification, related species are grouped together in the same genus, genera sharing common features are placed in the same family, and so on. Table A2 shows a modern classification scheme for the gut bacterium Escherichia coli.

The boundaries between long-standing divisions such as algae and protozoa have become considerably blurred in recent years, and alternative classifications based on molecular data have been proposed. This is very much a developing field, and no defini-tive alternative classification has yet gained universal acceptance.

We shall broadly follow the five-kingdom scheme, although of course the plant and animal kingdoms, having no microbial members, do not concern us.

It retains the traditional distinction between protozoans, algae and other protists (water moulds and slime moulds), but also offers an alternative, ‘molecular’ scheme, showing the putative phylogenetic relationship between the various groups of organisms. Microbiology has traditionally embraced anomalies such as the giant seaweeds, as it has encompassed all organisms that fall outside of the plant and animal kingdoms. This book offers only a brief consideration of such macroscopic forms, and for the most part confines itself to the truly microbial world.

Related Topics