Chapter: SHORT STORIES FOR CHILDREN kids

The Apricot Tree

The Apricot

Tree

M.S. Mahadevan

I have

lived in the

camp for close

to a year

now. When I remember

my old home,

somehow I love

it more than I

ever did. It was spring when we left.

And the barren,

grey mountains were slowly

turning green. The

apricot tree which my

grandfather had planted

as a young

man was heavy with

ripening fruit.

Abba and

Usman were making last minute

arrangements before taking our flock to

the high pastures. I begged

to go along with

them. "Not this

year," Abba had

said firmly.

In a

kinder voice he

had added, "Maybe

next summer."

Usman was

fifteen. I was

eleven. It seemed

like I would have

to wait forever

to be as

old as him. Meanwhile, there was

school to attend,

and Ammi and

Habiba to look

after.

"They are

your responsibility," Abba

had said proudly.

Usman, securing bags of barley flour, salt and dried meat, put them

onto a mule's

back, had given

me a sympathetic smile. I

envied him the

days of adventure

and freedom that lay

ahead. While I

would be in

school, cramming useless stuff like

tables and grammar,

he would be

out in the mountains,

fishing in the

streams, sleeping under

the dust in the distance and the

barking of dogs, an

echo in my head.

dust in

the distance and

the barking of dogs,

an echo in my

head.

Four days

later, the first

shell landed on

our village.

It came

across the ridge

and shattered the police

chowki.

The

third period had just begun. Our teacher Sadiq Ali was at the blackboard when there was

a loud, dull BOOM!

The walls shook. The

blackboard toppled off

its stand. Sadiq Ali's

spectacles fell off

his nose. The

rest of us

looked at each other

in astonishment. Before

Sadiq Ali could

stop us, we ran

out of the school

and up the

road to the

village square. We had

barely crossed the

grocery shop when another

shell landed on

it. When the

dust settled we saw that

one wall had

a big hole.

Through it we

could see the owner

cowering behind a

sack. He was

covered from head to toe with its contents-flour.

The

bombardment continued for another

hour. Six shells hit our

village. Several more

fell on the highway

and the river beyond.

A giant spray

of water splashed every

time a shell landed

in the river.

In the

late afternoon, a jeep

roared up into the

village square. A man

got up on

top of the

bonnet and yelled through a loudspeaker, "You

are informed that this village is under

attack by the

enemy (as if we

did not know

that already!). This is a war

zone. For your own safety,

you must evacuate your homes.

Take only the bare essentials.

Go to the camp at Drass.

Make sure that all women and

children leave the area."

He jumped off, got into the jeep

and roared off in the direction

of the next

village.

Our neighbours,

old Suleiman and

Amina refused to leave.

Chacha was ninety-five

years old. "I

can't leave my animals

behind," he said

angrily. "Who will

feed them?" "Fine then,

if you are

not going, neither

am I," Chachi said

emphatically.

"Don't be

stubborn," Ammi pleaded.

"This is a

matter of life and

death. Come along

with us."

"You go,

beti" Chachi said.

"Your children are

small.

When Arshad

miyan and Usman

come home, we

will tell them where

you have gone,

We will take

care of your animals

too."

Ammi

was unhappy about leaving

them behind. But what could she

do? There was hardly any

time. The villagers had begun

to leave; their

belongings-pots, pans and bags

of rations-piled on mule backs

or on their own heads. "Take

your school books,"

Ammi said. I was hoping

she would forget but I knew better than to

argue. She let Habiba take

her favourite doll

and a new

pair of shoes.

Ammi left a letter

for Abba.

We joined

the straggly line

heading for the

town. The narrow road

was chock-full of

army trucks loaded

with soldiers. In the

fields next to the river, men were

scurrying about carrying boxes

of ammunition, pitching

tents and setting up

big guns. We

made slow progress.

Habiba started to complain:

her new shoes

were pinching. She wanted

to take them

off and throw them away. Ammi picked her up

and carried her.

By sunset we

had covered only three

kilometres.

We spent

that night in

the open. It

was very cold.

The soldiers did not

allow us to

light fires. Habiba

snuggled with Ammi. I

had my own

blanket. I thought I

would not sleep a

wink. It was

a clear night.

Around us, a

ring of jagged peaks rose up to

meet the stars. Somewhere in those peaks were

Abba and Usman, thinking we were safe

in our beds! Would

I ever see

them again? Before I

knew it, the sun

was up and

Ammi was shaking me

awake. She looked tired,

as if she had

not slept a

wink. She gave

me the last of the

naans to eat.

It was hard

and dry but

I ate all of

it.

"Don't be

stubborn," Ammi pleaded.

"This is a

matter of life and

death. Come along

with us." "You go,

beti" Chachi said.

"Your children are

small.

When Arshad

miyan and Usman

come home, we

will tell them where

you have gone,

We will take

care of your animals

too."

Ammi

was unhappy about leaving

them behind. But what could she

do? There was hardly any

time. The villagers had begun

to leave; their

belongings-pots, pans and bags

of rations-piled on mule backs

or on their own heads. "Take

your school books,"

Ammi said. I

was hoping she

would forget but I knew better

than to

argue. She let Habiba take

her favourite doll

and a new

pair of shoes.

Ammi left a letter

for Abba.

We joined

the straggly line

heading for the

town. The narrow road

was chock-full of

army trucks loaded

with soldiers. In the

fields next to the river, men were

scurrying about carrying boxes

of ammunition, pitching

tents and setting up

big guns. We

made slow progress.

Habiba started to complain:

her new shoes

were pinching. She wanted

to take them

off and throw them away. Ammi picked her up

and carried her.

By sunset we

had covered only three

kilometres.

We spent

that night in

the open. It

was very cold.

The soldiers did not

allow us to

light fires. Habiba

snuggled with Ammi. I

had my own

blanket. I thought I

would not sleep a

wink. It was

a clear night.

Around us, a

ring of jagged peaks rose up to

meet the stars. Somewhere in those peaks were

Abba and Usman, thinking we were safe

in our beds! Would

I ever see

them again? Before I

knew it, the sun

was up and

Ammi was shaking me

awake. She looked tired,

as if she had

not slept a

wink. She gave

me the last of the

naans to eat. It

was hard and

dry but I

ate all of it Hurry," Ammi

said, "we must

be on our way

before the

shelling starts."

We passed two

villages. They were totally deserted.

There was not a

single house without

a roof or

a wall missing.

The

ruined village made me sad.

Everyone was quiet; even

Habiba. Just as

we passed the

last house, there

was a scuffling sound. Habiba

shrieked. A big, black head

stared at us dolefully

out through a

broken wall. It

was a yak.

It had

a little brass

bell that tinkled

when it shook

its head. It was

a cheerful sound.

The yak nuzzled its

head against Ammi. Its

eyes seemed to

plead.

"All right,"

said Ammi, "we won't leave you behind.

Come along." She made

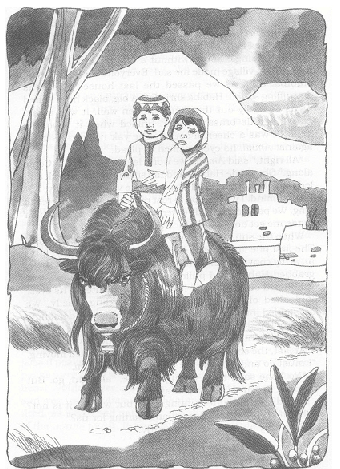

Habiba and me sit on the yak's back and led it by the rope around its neck. The yak was smelly, but I

didn't mind. I was happy to rest

my feet. Habiba started to sing. We passed a hillside covered with yellow

roses. Habiba made me

get down and

pluck a few for

her.

When the

sun was just over the ridge, the

shelling began.

The first

one landed just a few hundred

yards away. It hit an army convoy truck. A huge ball

of flame rolled out. Ammi grabbed

Habiba and pulled

me off the

yak. The yak

was frightened out of its wits.

I could see

the whites of its eyes.

It dashed

off into a

field, its bell

tinkling crazily. We scrambled

into a ditch

and lay low. Through

the deafening noise of the

shells came the

shouts of soldiers, the wails

of frightened children. I

kept listening for

the yak's bell.

At

last, the shelling

stopped. The convoy started moving.

"I must

go and look

for the yak," I

said to Ammi.

"No," she

said, then, seeing

my face, "all right, go.

But be back in

ten minutes. It

may be..."

"Dead?" I

said, interrupting her,

"but what if

it is not?

What if it

is alive and

scared and waiting

for us?"

"It is

only a yak," she

said gently.

It sounded

cruel to me.

Only a yak!

I clambered

out of the ditch

and ran into the

field. There were

huge craters where

the shells had

landed, as if a

giant hand had

clawed out the

earth. The yak

lay on the edge

of one crater.

It was still.

Beneath it was

a growing pool of blood.

I had never

felt so sad

as I did

then, looking at that poor,

gentle creature, now

dead. I looked

up at the mountains that had always

seemed friendly. Hiding in their

folds were men

who had so

casually destroyed my

whole world. What harm had we

ever done to

them?

I heard

footsteps. It was a

soldier, tall and strong.

With a beard and a

black turban. His

rifle was slung across

his shoulder. He looked

fierce, but when

he spoke, his

voice

was not

unkind. "Your mother

is waiting. It is

not safe for you

to be here.

We will give

you a ride

to town." Then he saw

the dead yak.

"Your friend?"

I nodded

glumly.

Bending down,

he took the

little brass bell off the

neck. "Keep this," he

said gently, "to

remind you of your friend."

He lifted

me across his

shoulder and walked

back.

We reached

the camp without

any mishap. The

first person I spotted

was Sadiq Ali.

"So you

have made it,"

he said in

his cool, precise

voice.

"School starts

tomorrow."

"But

we don't have a

schoolhouse!" I protested.

"We do,"

he grinned, pointing at a big,

shady tree. "Class

begins at 9

a.m."

Since then,

we have been

living in a

tent. It is crowded

but cosy. Abba

and Usman have

joined us. So

have old Suleiman and

Amina. The winter has

come and gone.

Abba went

to see our

house recently. "We

will have to build

a new one," he

said. "But the apricot tree

is fine, it is in

bloom."

................................End............................................

Related Topics