Chapter: Essential Clinical Immunology: Experimental Approaches to the Study of Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases

Progressive Systemic Sclerosis: Epidemiology, Etiology, Pathogenesis, Clinical Features, Treatment, Animal Models

PROGRESSIVE SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS

Introduction and Epidemiology

Progressive systemic sclerosis (PSS) is a disorder of connective tissue clinically characterized by thickening and fibrosis of the skin (scleroderma) and by distinctive forms of involvement of internal organs, including the heart, lungs, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract. The hall-marks of the disease are autoimmunity and inflammation, widespread vascu-lopathy (blood vessel damage), affecting multiple vascular beds, and progressive interstitial and perivascular fibrosis. The etiology is unknown. The incidence of sys-temic sclerosis is estimated to be between eighteen and twenty individuals per one million persons per year. All age groups may be affected, but the onset of disease is highest between the ages of thirty and fifty years old. Systemic sclerosis is three to four times more common in women than in men, with women of childbearing age at peak risk.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis involves an interplay between oblitera-tive vasculopathy in multiple vascular beds, inflammation, and autoimmunity, and progressive fibrosis. Vascular injury and activation are the earliest and possibly primary events in the pathogenesis of PSS. This is suggested by histopathological evi-dence of vascular damage that is present before fibrosis, and clinical manifestations, such as Raynaud’s phenomenon, an epi-sodic and reversible cold-induced vaso-spasm of the fingers and toes, that precede other disease manifestations. Additional manifestations of PSS-associated vascu-lopathy include cutaneous telangiectasia, nail-fold capillary alterations, pulmo-nary arterial hypertension, gastric antral vascular ectasia, and scleroderma renal crisis with malignant hypertension. In late-stage PSS, there is a striking paucity of small blood vessels in lesional skin and other organs. Endothelial cell injury might be triggered by granzymes, endothe-lial cell-specific autoantibodies, vasculo-tropic viruses, inflammatory cytokines, or reactive oxygen radicals generated during ischemia/reperfusion.

Clinical Features

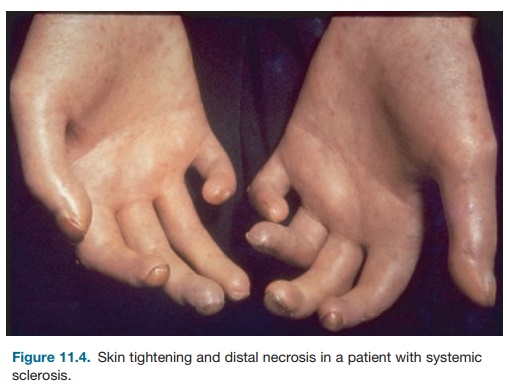

Patients with systemic sclerosis have a wide array of symptoms and difficulties, ranging from complaints related to spe-cific internal organ involvement as well as the symptoms of a chronic catabolic illness. Raynaud’s phenomenon is the initial complaint in approximately 70 per-cent of patients with systemic sclerosis. Peripheral vasoconstriction in response to cold is physiologic, and individu-als with Raynaud’s, no matter the cause, have undue intolerance to environmental cold. The digital arteries of patients with systemic sclerosis exhibit marked intimal hyperplasia as well as adventitial fibro-sis. Severe narrowing (more than 75 per-cent) of the arterial lumen results, which may be sufficiently severe to account for Raynaud’s phenomenon. The skin thick-ening of systemic sclerosis begins on the fingers and hands in nearly all cases. The skin initially appears shiny and taut and may be erythematous at early stages (Figure 11.4). The skin of the face and neck is usually involved next and is associated with an immobile and pinched facies. The skin change may stay restricted to fingers, hands, and face and may remain rela-tively mild. Extension to the forearms is often followed by rapid centripetal spread to the upper arms, shoulders, anterior chest, back, abdomen, and legs (diffuse scleroderma).

Involvement of the gastrointestinal tract is the third most common manifestation of systemic sclerosis. Impaired function of the lower esophageal sphincter is associated with symptoms of intermittent heartburn,

Figure 11.4. Skin tightening and distal necrosis in a patient with systemic sclerosis.

typically described as a retrosternal burn-ing pain. Complications of chronic esoph-ageal reflux include erosive esophagitis with bleeding, Barrett’s esophagus, and lower esophageal stricture. Small-bowel involvement is encountered in patients with longstanding disease. Symptoms include intermittent bloating with abdom-inal cramps, intermittent or chronic diarrhea, and presentations suggestive of intestinal obstruction.

Pulmonary involvement is the leading cause of mortality and a principal source of morbidity in systemic sclerosis. Pathologi-cal processes operative in scleroderma lung include combinations of vascular oblitera-tion, fibrosis, and inflammation. Patients with diffuse scleroderma are at risk for progressive interstitial fibrotic lung disease and pulmonary arterial hypertension. The clinical onset of pulmonary involvement is frequently insidious and characterized by progressive dyspnea on exertion, lim-ited effort tolerance, and a nonproductive cough. Other organs involved in systemic sclerosis include the musculoskeletal sys-tem, with arthralgias, arthritis, and myo-sitis as potential manifestations, as well as the heart and kidney.

Treatment of Progressive Systemic Sclerosis

No drug therapies are available for the management of systemic sclerosis that have been proven to enhance survival, pre-vent internal organ involvement, or slow, halt, or improve deterioration of function of involved organs, including the skin. In the absence of such agents, management is directed at treating manifestations of the disease. NSAIDs are generally useful in managing arthralgias and myalgias, although occasional patients require low-dosage oral glucocorticoids. Symptoms of reflux esophagitis are typical of systemic sclerosis but generally amenable to ther-apy with H2 blockers and protein pump inhibitors. Pulmonary involvement has generally not been considered amenable to therapy. A patient in whom there is evi-dence of pulmonary interstitial inflamma-tion might be treated with glucocorticoids and immunosuppressive agents. A recent double-blind, randomized, placebo-con-trolled trial to determine the effects of oral cyclophosphamide on lung function and health-related symptoms in patients with evidence of active alveolitis and sclero-derma-related interstitial lung disease reported a significant but modest ben-eficial effect on lung function, dyspnea, thickening of the skin, and health-related quality of life. Pulmonary hyperten-sion has emerged as a principal cause of morbidity and mortality in late systemic sclerosis. Centrally infused prostacyclin (epoprostenol) improves both short- and long-term hemodynamics, as well as the quality of life and survival. Studies have demonstrated that treatment with the oral endothelin receptor anatagonist bosen-tan is well tolerated in PSS patients with interstitial lung disease and is effective for treatment of severe pulmonary hyperten-sion in study patients. Scleroderma renal crisis demands prompt recognition of the diagnosis and aggressive treatment of the accompanying accelerated hyper-tension. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors such as captopril and enala-pril are mechanistically ideal to treat the hyperreninemic hypertension of sclero-derma renal crisis and are the treatment of choice.

Animal Models of Progressive Systemic Sclerosis

The pathogenesis of PSS involves a triad of small-vessel vasculopathy; inflamma-tion, and autoimmunity; and interstitial and vascular fibrosis in the skin, lungs, and multiple other organs. Various animal models have been investigated as spontaneous or inducible models for SSC. Although none of them reproduce all three pathogenetic components of the disease, some models do recapitulate selected phenotypic features. Two useful animal models of PSS include bleomy-cin-induced skin fibrosis and the chronic graft-versus-host disease system, which results in skin fibrosis. In addition, the tight skin (Tsk-1) mouse has been pro-posed as a model for PSS based on skin pathology that is similar to that of the human disease, with increased accumula-tion of collagen and glycosaminoglycans in the skin and production of serum auto-antibodies. The gene mutated in the Tsk-1 mouse isfibrillin-1, whose product can form a part of elastic fibers.

Related Topics