Chapter: Psychology: Memory

Memory Gaps, Memory Errors: Forgetting

Forgetting

There are many reasons why we

sometimes cannot recall past events. In many cases, as we’ve noted, the problem

arises because we didn’t learn the relevant information in the first place! In

other cases, though, we learn something—a friend’s name, the lyrics to a song,

the content of the Intro Bio course—and can remember the information for a

while; but then, sometime later, we’re unable to recall the information we once

knew. What produces this pattern?

One clue comes from the fact that

it’s almost always easier to recall recent events (e.g., yesterday’s lecture or

this morning’s breakfast) than it is to recall more distant events (a lecture

or a breakfast 6 months ago). In technical terms, recall decreases, and

forgetting increases, as the retention

interval (the time that elapses between learning and retrieval) grows

longer and longer.

This simple fact has been

documented in many studies; indeed, the passage of time seems to work against

our memory for things as diverse as past hospital stays, our eating or smoking

habits in past years, car accidents we experienced, our con-sumer purchases,

and so on (Jobe, Tourangeau, & Smith, 1993). The classic demon-stration of

this pattern, though, was offered more than a century ago by Hermann Ebbinghaus

(1850–1909). Ebbinghaus systematically studied his own memory in a series of

careful experiments, examining his ability to retain lists of nonsense sylla-bles,

such as zup and rif. (Ebbinghaus relied on these odd stimuli as a way of making

sure he came to the memory materials with no prior associations or links; that

way, he could study how learning proceeded when there was no chance of

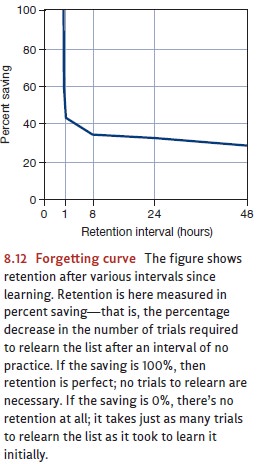

influence from prior knowledge.) Ebbinghaus plotted a forgetting curve by testing himself at vari-ous intervals after

learning (using different lists for each interval). As expected, he found that

memory did decline with the passage of time. However, the decline was uneven;

it was sharpest soon after the learning and then became more gradual

(Ebbinghaus, 1885; Figure 8.12).

There are two broad ways to think

about the effect of retention interval. One per-spective emphasizes the passage

of time itself—based on the idea that memories decay as time passes, perhaps because normal metabolic processes

wear down the memory traces until they fade and finally disintegrate. A

different perspective suggests that time itself isn’t the culprit. What matters

instead is new learning—based on the

idea that new information getting added to long-term memory somehow disrupts

the old informa-tion that was already in storage. We’ll need to sort through

why this disruption might happen; but notice that this perspective, too,

predicts that longer retention intervals will lead to more forgetting—because

longer intervals provide more opportunity for new learning and thus more

disruption from the new learning.

Which perspective is correct? Is

forgetting ultimately a product of the passage of time, or a product of new

learning? The answer is both. The

passage of time, by itself, does seem to erode memories (e.g., E. Altmann &

Gray, 2002; C. Bailey & Chen, 1989; Wixted, 2004); but the effect of new

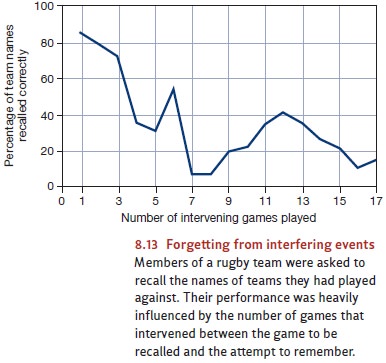

learning seems larger. For example, Baddeley and Hitch (1977) asked rugby

players to recall the names of the other teams they had played against over the

course of a season; the researchers then systematically compared the effect of timewith the effects of new learning. To examine the effects of

time, Baddeley and Hitch capitalized on the fact that not all players made it

to all games (because of illness, injuries, or schedule conflicts). These

differences allowed them

to compare players

for whom “two games back” means 2 weeks ago, to players for whom “two

games back” means 4 weeks ago. Thus, they were able to look at the effects of

time (2 weeks vs. 4) with the number of more recent games held constant.

Likewise, to examine the effects of new learning, these researchers compared

(say) players for whom the game a month ago was “three games back” to players

for whom a month ago means “one game back.” Now we have the retention interval

held constant, and we can look at the effects of intervening events. In this

setting, Baddeley and Hitch report that the mere passage of time accounts for

very little; what really matters is the number of inter-vening events—just as

we’d expect if intervening learning, and not decay, is the major con-tributor

to forgetting (Figure 8.13). (For other—classic—data on this issue, see Jenkins

& Dallenbach, 1924; for a more recent review, see Wixted, 2004.)

An effect of new learning undoing

old learning can also be demonstrated in the lab-oratory. In a typical study, a

control group learns the items on a list (A) and then is tested after a

specified interval. The experimental group learns the same list (A), but they

must also learn the items on a second list (B) during the same retention

interval. The result is a marked inferiority in the performance of the

experimental group. List B seems to interfere with the recall of list A

(Crowder, 1976; McGeoch & Irion, 1952).

Of course, not all new learning produces this disruption. No interference is observed, for example, between dissimilar sorts of material—and so learning to skate doesn’t undo your memory for irregular French verbs. In addition, if the new learning is consistent with the old, then it certainly doesn’t cause disruption; instead, the new learning actually helps memory. Thus, learning more algebra helps you remember the algebra you mastered last year; learning more psychology helps you remember the psy-chology you’ve already covered.

Related Topics