Chapter: Essential Anesthesia From Science to Practice : Applied physiology and pharmacology : A brief pharmacology related to anesthesia

The opioids

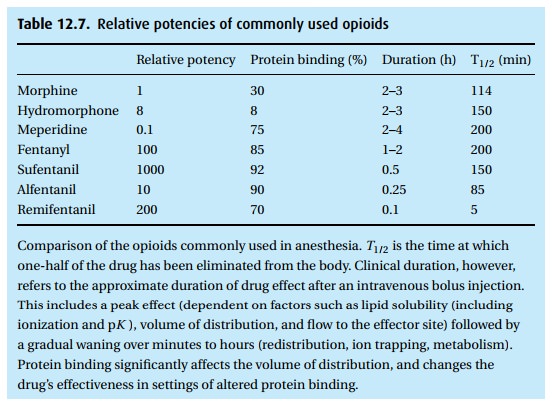

The opioids (Table 12.7)

Today,

narcotics play a major role in general anesthesia. Their advantage lies in

their potent ability to abolish pain without depressing the heart. Their

principle

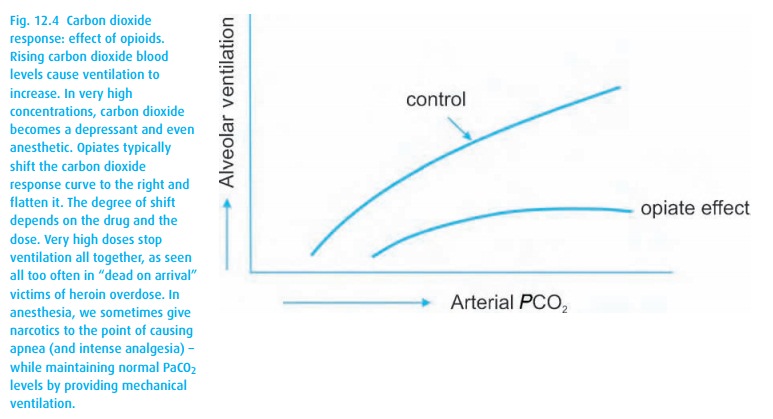

This side effect can be tol-erated if we are prepared to ventilate the

patient’s lungs, as we do routinely when patients receive neuromuscular

blocking drugs and thus require mechanical ven-tilation. Unchecked respiratory

depression and elevation of arterial carbon diox-ide can reduce resistance in

the arterial bed of the cerebral circulation, leading to increased intracranial

pressure. Chemoreceptor depression by opioids reduces the respiratory response

to hypoxemia; however, the administration of oxygen to a hypoxemic patient may

further depress ventilation, demonstrating that chemo-receptor activity still

contributes to the respiratory drive.

At this

time in anesthesia, we have no useful opioid that would spare the µ-2 receptors

responsible for respiratory depression, while exerting a full effect on the

receptors apparently involved in analgesia (µ-1, δ-1, δ-2 and κ-3 for

supraspinal analgesia, and µ-2, δ-2 and κ-1 for spinal analgesia). As mentioned

in the brief his-torical piece, to be eaten alive by a lion may not be painful,

presumably because the endogenous opioid polypeptides (the enkephalins,

endorphins, dynorphins and neoendorphins) kick in – evidently without causing

fatal respiratory depres-sion but presumably allowing for a gasp. We tend not

to rely on this physio-logic response to gourmand lions, even with the most

fearsome of surgeons at work.

Opioids

exhibit many side effects other than respiratory depression. Interesting to

anesthesia are the depressant effects on the autonomic nervous system with a

decrease in sympathetic tone and a preponderance of vagal activity, leading to

bradycardia and a reduction in blood pressure. The observed hypotension after

large doses of opioids gives evidence of venous pooling (exaggerated in

patients with a reduced blood volume) rather than a direct depressant effect on

the heart. Meperidine, having vagolytic effects, behaves somewhat differently.

During a

cholecystectomy, we need to be aware that opioids can increase the tone of the

sphincter of Oddi, thereby increasing pressure in the biliary system and interfering

with a surgeon’s attempt to perform a cholangiogram.

Opioids

have numerous side effects in addition to respiratory depression. These range

from miosis (the infamous pin-point pupils – again meperidine is the

excep-tion), itching, constipation and nausea, to changes in mood (either

euphoria or dysphoria, depending on the setting and the patient). Some of these

effects have their origin locally (constipation), others centrally

(chemoreceptor stimulation triggering nausea).

By now

the opioids have amassed quite a retinue of narcotic compounds, some of which

appear to have unrelated chemical footprints. While heroin, codeine, and many

relatives show their kinship with morphine, others are classified as

piperidines and phenylpiperidines, comprising meperidine and the different

fen-tanyl drugs.

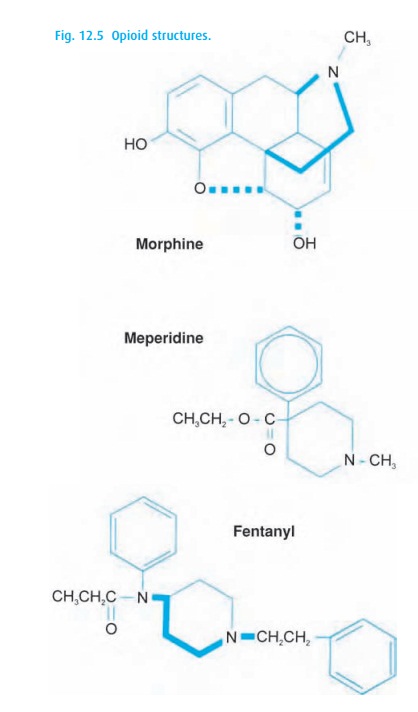

Morphine

Morphine

(Fig. 12.5) has a long tradition as an

analgesic for wound pain with a typical i.m. dose of 10 mg for a 70 kg patient.

Despite its propensity to stimulate his-tamine release, we make extensive use of

i.v. morphine for management of acute pain, as an intra-operative analgesic and

adjunct to general anesthesia, and post-operatively as the most common drug for

patient-controlled analgesia (PCA). We also commonly administer morphine

neuraxially (epidural or subarachnoid) to obtain 18–24 hours of post-surgical

analgesia, though delayed respiratory depres-sion remains a concern. One of its

metabolites, morphine-6-glucuronide, retains much of morphine’s activity and

has been implicated in prolonged respiratory depression observed in patients

with renal failure.

Meperidine (pethidine, Demerol®, Dolantin®, Pethadol®)

Another

synthetic opioid, meperidine, deserves to be mentioned, though in anes-thesia

we use it less today than before the arrival of its chemical grandchildren, the

fentanyls. Meperidine (Fig. 12.5), with 1/10

the potency and shorter dura-tion of action than morphine, occupies a unique

spot among opioids in its anti-muscarinic activity. Patients receiving

meperidine do not develop the “pin-point pupils” we expect with other opioids;

they may also become tachycardic and complain of a dry mouth. The drug can be

associated with nausea and vomiting as well. Most importantly, it should not be

given to patients taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors because severe

respiratory depression, excitation, and even convulsions can be the consequence

(serotonin syndrome). Meperidine’s main metabolite, normeperidine, lasts for

days (T1/2 elimination = 15–40 h). Particularly in the setting of impaired renal function, the

accumulation of normeperidine can cause myoclonus and seizures.

Fentanyls

Fentanyl (Sublimaze®) (Fig. 12.5), with a potency 100 times that of morphine, has even more potent offspring. The growing list includes 3-methyl fentanyl, lofentanyl, and etorphin being several thousand-fold as potent as morphine. None have made it into the operating room. Nor are they needed as potency in the clinical setting means relatively little as long as the desired effect can be reached by adjusting the dose, and as long as that dose can be readily delivered. Clinical doses of the fentanyls are all in the microgram/kg range, thus posing no difficulty to intravenous administration.

The

differences among the fentanyls reside primarily in the duration of action,

since, in general, the respiratory depressant effect runs parallel with the

analgesic effectiveness. There are small differences in the onset of action

after an intra-venous bolus, with fentanyl and sufentanil (Sufenta®) taking

about 6 minutes for the peak effect to set in while alfentanil (Alfenta®) and

remifentanil (Ultiva®) reach their peaks in about a minute. Remifentanil, an

ester, deserves special men-tion as the only narcotic that falls prey to

non-specific plasma esterases that hydrolyze the drug, thus rapidly curtailing

its effect. The other opioids have to rely on liver blood flow and hepatic

biotransformation. A comparison of each of the commonly used opioids may be of

help (Table 12.7).

Finally,

let us mention that narcotic addiction has not spared anesthesia and nursing

personnel. Easy access to narcotics has been blamed for the higher frequency of

addiction among anesthesia personnel than other health care workers.

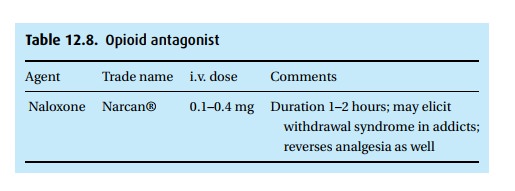

Opioid receptor antagonism: naloxone (Narcan®)

Opioids

are antagonized by naloxone, chemically related to morphine and com-peting for

receptor sites occupied by the agonists (See Table 12.8).

In the adult, we usually start with 40–100 mcg naloxone intravenously,

expecting to see a response within a minute. The half-life of the drug is

around 40 minutes. Thus, patients who had been depressed by the longer acting

drugs, such as morphine, must be observed for at least an hour in order not to

miss recurring respiratory depression. In addicted patients under the influence

of and tolerant to large doses of a narcotic analgesic, a larger dose of

naloxone can trigger a stormy withdrawal reaction, as can administration of

some of the mixed agonist-antagonist drugs, among them butorphanol (Stadol®)

and nalbuphine (Nubain®). These latter agents have a ceiling effect on

respiratory depression, a property considered vital in obstetrics where they

are commonly used – never mind that the patient’s pain is not much relieved by

these agents!

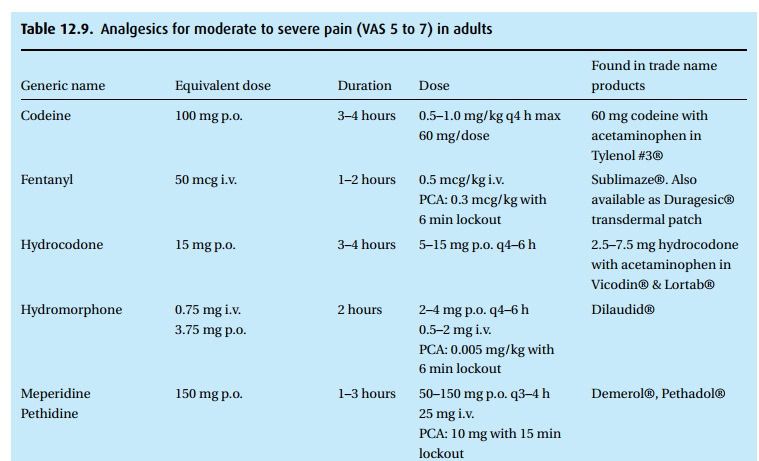

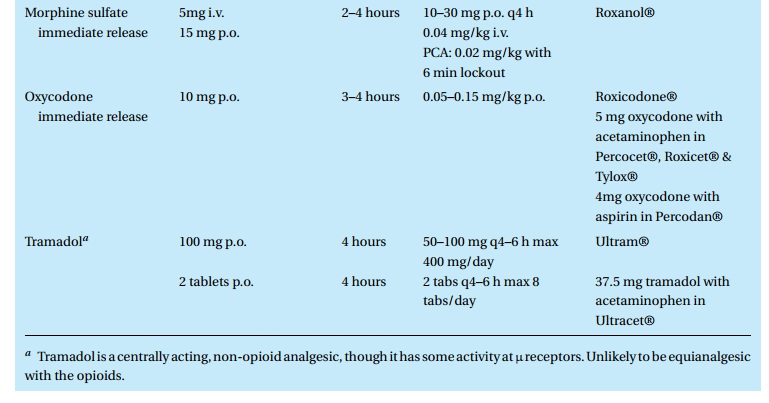

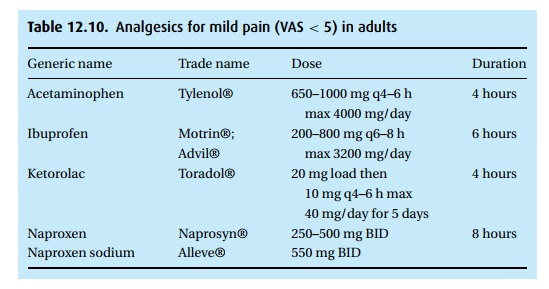

Clinical perspectives on the use of analgesics

In the

chapter on Post-operative care, you will find a discussion of how to assess the

severity of pain. Many different drugs find use in the treatment of pain. The

following tables are not intended to guide therapy, but are presented here for

the sake of orientation. We do not offer a discussion of these drugs and urge

the reader to consult pharmacologic texts and the information offered by the

manufacturers. For moderate to severe pain (VAS 5 to 7), you may see one of the

drugs in Table 12.9prescribed. For mild pain

we often use one of the common oral, non-narcotic analgesics that are available

over the counter (Table 12.10).

Related Topics