Chapter: Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing : Grief and Loss

The Grieving Process

THE GRIEVING PROCESS

Nurses interact with clients responding to myriad losses along the

continuum of health and illness. Regardless of the type of loss, nurses must

have a basic understanding of what is involved to meet the challenge that grief

brings to clients. By understanding the phenomena that clients![]()

![]() experience as they deal with the discomfort of

loss, nurses may promote the expression and release of emotional as well as

physical pain during grieving. Supporting this process means ministering to

psychological—and physical—needs.

experience as they deal with the discomfort of

loss, nurses may promote the expression and release of emotional as well as

physical pain during grieving. Supporting this process means ministering to

psychological—and physical—needs.

The therapeutic relationship and therapeutic commu-nication skills

such as active listening are paramount when assisting grieving clients.

Recogniz-ing the verbal and nonverbal communication content of the various

stages of grieving can help nurses to select interventions that meet the

client’s psychological and physical needs.

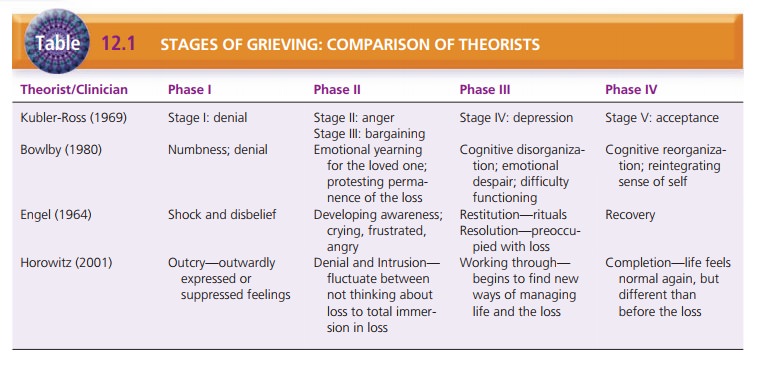

Theories of Grieving

Among well-known theories of

grieving are those posed by Elizabeth Kubler-Ross, John Bowlby, George

Engel, and Mardi Horowitz.

Kubler-Ross’s Stages of Grieving

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross (1969) established a basis for under-standing

how loss affects human life. As she attended to clients with terminal

illnesses, a process of dying became apparent to her. Through her observations

and work with dying clients and their families, Kubler-Ross developed a model

of five stages to explain what people experience as they grieve and mourn:

·

Denial is shock and disbelief

regarding the loss.

·

Anger may be expressed toward God,

relatives, friends, or health care

providers.

·

Bargaining occurs when the person asks

God or fate for more time to delay

the inevitable loss.

·

Depression results when awareness of the

loss becomes acute.

·

Acceptance occurs when the person shows

evidence of coming to terms with

death.

This model became a prototype for care providers as they looked for

ways to understand and assist their clients in the grieving process.

Bowlby’s Phases of Grieving

John Bowlby, a British psychoanalyst, proposed a theory that humans

instinctively attain and retain affectional bonds with significant others

through attachment behav-iors. These

attachment behaviors are crucial to the development

of a sense of security and survival. People experience the most intense

emotions when forming a bond such as

falling in love, maintaining a bond

such as loving someone, disrupting a

bond such as in a divorce, and renewing

an attachment such as resolving a conflict or renewing a relationship (Bowlby,

1980). An attach-ment that is maintained is a source of security; an

attach-ment that is renewed is a source of joy. When a bond is threatened or

broken, however, the person responds with anxiety, protest, and anger.

Bowlby described the grieving process as having four phases:

·

Experiencing numbness and denying the loss

·

Emotionally yearning for the lost loved one and pro-testing the

permanence of the loss

·

Experiencing cognitive disorganization and emotional despair with

difficulty functioning in the everyday world

·

Reorganizing and reintegrating the sense of self to pull life back

together.

Engel’s Stages of Grieving

George Engel (1964) described five stages of grieving as follows:

·

Shock and disbelief: The initial reaction to a

loss is a stunned, numb feeling

accompanied by refusal to ac-knowledge the reality of the loss in an attempt to

pro-tect the self against overwhelming stress.

·

Developing awareness: As the individual begins to

ac-knowledge the loss, there may be crying, feelings of helplessness,

frustration, despair and anger that can be directed at self or others,

including God or the deceased person.

·

Restitution: Participation in the rituals

associated with death, such as a

funeral, wake, family gathering, or religious ceremonies that help the

individual accept the reality of the loss and begin the recovery process.

·

Resolution of the loss: The individual is preoccupied with the loss, the lost person or

object is idealized, the mourner may even imitate the lost person. Eventually,

the preoccupation decreases, usually in a year or per-haps more.

·

Recovery: The previous preoccupation

and obsession ends, and the individual

is able to go on with life in a way that encompasses the loss.

Horowitz’s Stages of Loss and Adaptation

Mardi Horowitz (2001) divides normal grief into four stages of loss

and adaptation:

·

Outcry: First realization of the loss. Outcry may be out-ward, expressed by

screaming, yelling, crying, or col-lapse. Outcry feeling can also be suppressed

as the person appears stoic, trying to maintain emotional con-trol. Either way,

outcry feelings take a great deal of energy to sustain and tend to be short-lived.

·

Denial and intrusion: People move back and forth

dur-ing this stage between denial and intrusion. During de-nial, the person

becomes so distracted or involved in activities that he or she sometimes isn’t

thinking about the loss. At other times, the loss and all it represents

intrudes into every moment and activity, and feelings are quite intense again.

Working through: As time passes, the person

spends less time bouncing back and

forth between denial andintrusion, and the emotions are not as intense and

over-whelming. The person still thinks about the loss, but also begins to find

new ways of managing life after loss.

·

Completion: Life begins to feel “normal”

again, although life is different

after the loss. Memories are less painful and don’t regularly interfere with

day-to-day life. Epi-sodes of intense feelings may occur, especially around

anniversary dates, but are transient in nature.

Table 12.1 compares the stages of grieving theories.

Tasks of Grieving

Grieving tasks, or mourning, that the

bereaved person faces involve active

rather passive participation. It is some-times called “grief work” because it

is difficult and requires tremendous effort and energy to accomplish.

Rando (1984) describes tasks inherent to grieving that she calls

the “six R’s”:

·

Recognize: Experiencing the loss, and

understanding that it is real, it has

happened.

·

React: Emotional response to loss,

feeling the feelings.

·

Recollect and re-experience: Memories are reviewed and relived.

·

Relinquish: Accepting that the world has

changed (as a result of the loss),

and there is no turning back.

·

Readjust: Beginning to return to daily

life; loss feels less acute and

overwhelming.

·

Reinvest: Accepting changes that have

occurred; re-entering the world, forming new relationships and commitments.

Worden (2008) views the tasks of grieving as follows:

1.

Accepting the reality of the loss: It is common for peo-ple

initially to deny that the loss has occurred, it is toopainful to be

acknowledged fully. Over time, the person wavers between belief and denial in

grappling with this task. Traditional rituals, such as funerals and wakes, are

helpful to some individuals.

2. Working through the pain of

grief: A loss causes pain, both physical and emotional, that must be

acknowl-edged and dealt with. Attempting to avoid or suppress the pain may

delay or prolong the grieving process. The intensity of pain and the way it is

experienced varies among individuals, but it needs to be experienced for the

person to move forward.

3. Adjusting to an environment

that has changed because of the loss. It may take months for the person to

realize what life will be like after the loss. When a loved one dies, roles

change, relationships are absent or different, lifestyle may change, and the

person’s sense or identity and self-esteem may be greatly affected. Feelings of

fail-ure, inadequacy, or helplessness at times are common. The individual must

develop new coping skills, adapt to the new or changed environment, find

meaning in the new life, and regain some control over life to con-tinue to

grow. Otherwise, the person can be in a state of arrested development and get

stuck in mourning.

4. Emotionally relocating that

which has been lost and moving on with life. The bereaved person identifies a

special place for what was lost and the memories. The lost person or

relationship is not forgotten or diminished in importance, but rather is

relocated in the mourner’s life as the person goes on to form new relationships,

friends, life rituals, and moves ahead with daily life.

Related Topics