Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Sterilization

Sterilization of Women

STERILIZATION OF WOMEN

Surgical sterilization techniques for women can be per-formed by laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, minilaparotomy, or transvaginally. Sterilization can be performed as an intervalprocedure, after a spontaneous or elective abortion, or as a postpartum procedure at the time of caesarean delivery or following vaginal delivery.

Some

nonsurgical methods based on prin-ciples of immunization as well as sclerosing

agents are under investigation, but remain experimental although promising.

Regardless of the method chosen, patients should be counseled about the various

components of the procedure, effectiveness rates, and possible complications.

Failure rates of tubal sterilization are roughly comparable with those of the

intrauterine contraceptive (IUC). Pregnancy should also be ruled out prior to

performing any steriliza-tion procedure.

Laparoscopy

Performed as an outpatient

interval procedure, laparo-scopic techniques may be carried out under local,

regional, or general anesthesia. Small incisions, a relatively low rate of

complica-tions, and a degree of flexibility in the procedures have led to high

physician and patient acceptability.

Occlusion

of the fallopian tubes may be accom-plished through the

use of electrocautery (unipolar or bipo

The choice among laparoscopic methods and cautery or occlusive de-vice is often

based more on operator experience, training, and personal preference than on

outcome data.

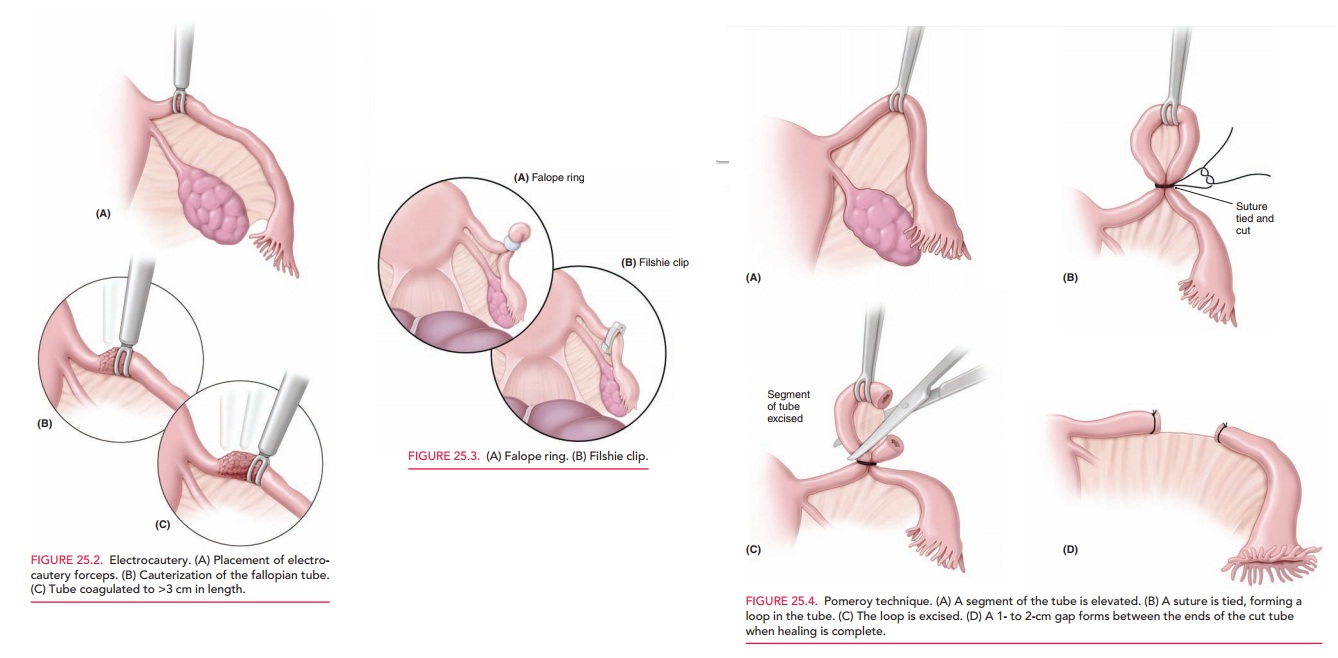

Electrocautery-based

methods are fast, but theycarry a risk of inadvertent

electrical damage to other struc-tures, poorer reversibility, and greater

incidence of ectopic pregnancies when failure does occur. Most operators

co-agulate at the isthmus, taking care that the coagulation forceps is placed

over the entire fallopian tube and onto the mesosalpinx so that the entire tube

and its lumen are coagulated >3 cm in length. Bipolar cautery is safer than

unipolar; it has less risk of spark injury to adjacent tissue, because the

current passes directly between the blades of the coagulation forceps (Fig.

25.2). Unipolar cautery, how-ever, has a

lower failure rate than bipolar. The surgeon,therefore, needs to carefully

weigh the risk of the individ-ual procedure with its respective effectiveness.

The Hulka clip is the most readily reversible method because of its

minimal tissue damage, but it also carries the greatest failure rate (>1%)

for the same reason. As in co-agulation, care must be taken to place the jaws

of the Hulka clip over the entire breadth of the fallopian tube at 90-degree

angle. This can be especially difficult when performed immediately postpartum,

due to the natural edematous dilation of the tubes.

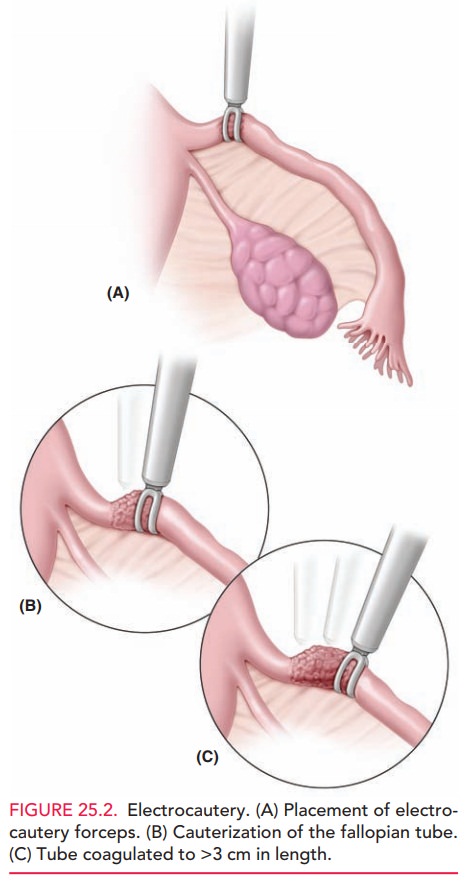

The Falope ring is intermediate for both reversibility and failure

rates. Patients may, however, have a higher in-cidence of postoperative pain,

requiring strong analgesics. Care must be taken to draw a sufficient “knuckle”

of fallo-pian tube into the Falope ring applicator so that the band is placed

below the outer and inner borders of the fallopian tube, thus occluding the

lumen completely (Fig. 25.3A). Bleeding is a potential complication if too much

pressure is placed on the mesosalpinx during the application of the ring.

The Filshie clip has a lower failure rate than the Hulka clip, because of its larger diameter, ease of applica-tion, and atraumatic locking device (Fig. 25.3B). To maximize effectiveness, this clip should be placed at the isth-mic portion of the fallopian tube.

Minilaparotomy

Minilaparotomy

is the most common surgical approach for tubal ligation throughout the world. Minilaparotomy

can be ac-complished with a small infraumbilical incision made in the

postpartum period or a small lower abdominal supra-pubic incision used as an

interval procedure, both of which provide ready access to the uterine tubes.

Occlusion of the fallopian tubes may then be accomplished by excision of all or

part of the fallopian tube or the use of clips, rings, or cautery.

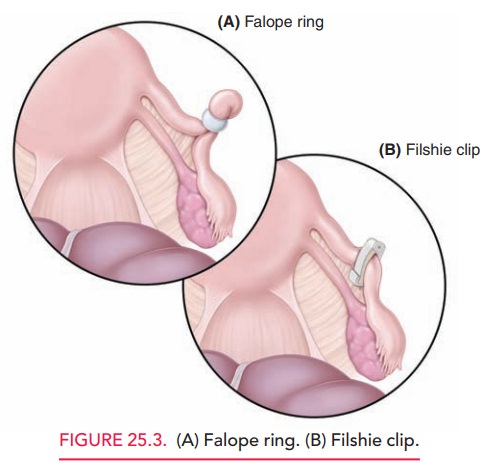

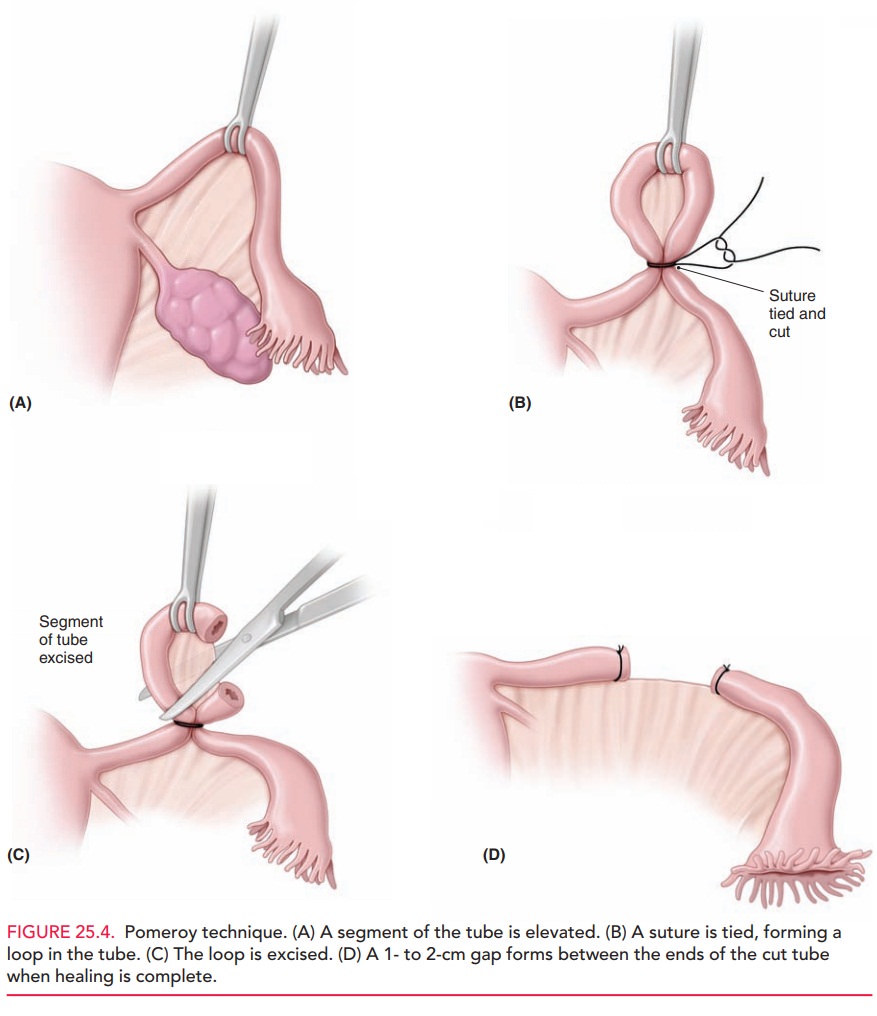

A common method of tubal interruption done in minila-parotomy is the Pomeroy tubal ligation (Fig. 25.4).

In this procedure, a segment of tube from

the midportion is elevated, and an absorbable ligature is placed across the

base, form-ing a loop, or knuckle, of tube. This knuckle is then ex-cised.

Because of the similarity in appearance between the fallopian tube and the

round ligament, this tissue is sent for histologic confirmation. When healing

is complete, the ends of the tube will have sealed closed, with a 1- to 2-cm

gap between the ends. Electrocoagulation or the ap-plication of clips or bands

may also be accomplished through a minilaparotomy incision, although these are

more widely used with laparoscopy.

Transvaginal Approach

The thin wall of tissue between

the vaginal canal and the posterior cul-de-sac also offers a convenient port of

entry into the peritoneal cavity for sterilization procedures. Advantages include less patient preparation

(e.g., bladder catheter-ization), the absence of abdominal incision, and

potentially less pain for the patient, with an earlier return to routine

activity. Contraindications include suspicion of major pelvic adhe-sions,

enlarged uterus, and inability to place the patient in the lithotomy position.

One major disadvantage is the need for adequate vaginal surgical training to

minimize potential complications, such as cellulitis, pelvic abscess,

hemor-rhage, proctotomy, or cystotomy.

Hysteroscopy

Transcervical approaches to sterilization include hysteroscopy and involve gaining access to the fallopian tubes through the cervix. The only currently available hysteroscopic steriliza-tion method involves the placement of a titanium-Dacronspring device directly into the tubal ostia bilaterally.

Theinserts stimulate a tissue reaction that ultimately leads to tubal occlusion. Patients are

instructed to use an additional form of contraception for 3 months after the

procedure, until the efficacy of the device can be proven with hys-terosalpingography. Contraindications

include nickelor contrast allergies, active pelvic infection, and sus-pected

pregnancy. Patients should be pretreated

with eitherdepomedroxyprogesterone (DMPA) or continuous combined oral

contraceptive pills, which ensures a thin endometrial lining, enhances

visualization, and improves the success rate of the pro-cedure. This

procedure can be used for obese patients whomay otherwise not be suitable

candidates for laparoscopic tubal ligation due to their body habitus. The

efficacy for this procedure has been reported to be as great as 99.8%.

Side Effects and Complications

No surgically-based technology is

free of the possibility of complications or side effects. Infection, bleeding,

injury to surrounding structures, or anesthetic complications may occur with

any of the techniques discussed. The overall fatality rate attributed to

sterilization is about 1–4 per 100,000 procedures, significantly lower than

that for childbearing in the United States, estimated at about 10 per 100,000

births.

Although

pregnancy after sterilization is uncommon, there is substantial risk that any

post-sterilization pregnancies will be ectopic. The risk

varies with the type of procedure and the age of the patient. Ectopic pregnancy

occurs after tubal lig-ation more commonly after cautery than after mechanical

tubal occlusion, probably because of microscopic fistulae in the coagulated

segment connecting to the peritoneal cavity. Overall, the 10-year cumulative

probability of ectopic preg-nancy after tubal ligation is 7.3 per 1000

procedures.

Noncontraceptive Benefits

Patients who undergo a tubal

ligation not only gain effec-tive contraception; they also benefit from a

decreased life-time risk of ovarian cancer. The mechanism for this risk

reduction is unknown at this time. Although tubal steril-ization has not been

shown to protect against sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), it may offer

some protection against pelvic inflammatory disease.

Related Topics