Chapter: Medical Physiology: Circulatory Shock and Physiology of Its Treatment

Relationship of Bleeding Volume to Cardiac Output and Arterial Pressure

Relationship of Bleeding Volume to Cardiac Output and Arterial Pressure

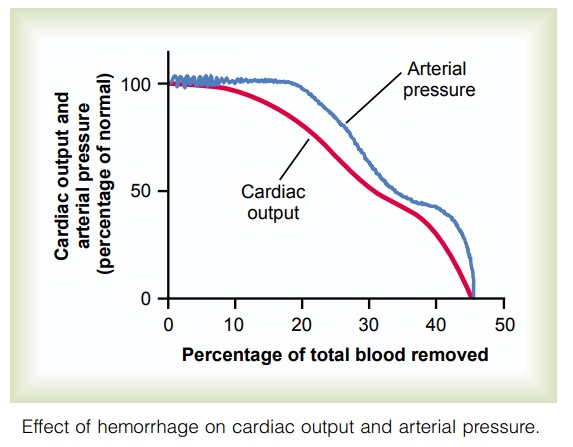

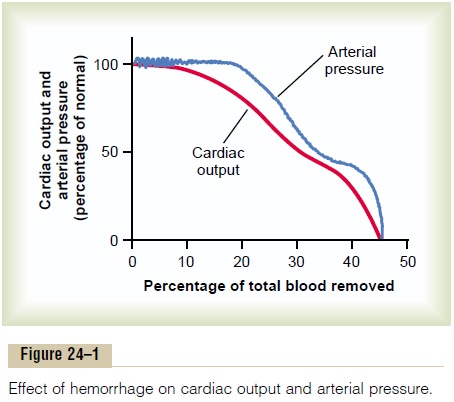

Figure 24–1 shows the approximate effects on both cardiac output and arterial pressure of removing blood from the circulatory system over a period of about 30 minutes. About 10 per cent of the total blood volume can be removed with almost no effect on either arte-rial pressure or cardiac output, but greater blood loss usually diminishes the cardiac output first and later the arterial pressure, both of which fall to zero when about 35 to 45 per cent of the total blood volume has been removed.

Sympathetic Reflex Compensations in Shock—Their Special Value to Maintain Arterial Pressure. The decrease in arte-rial pressure after hemorrhage—as well as decreases in pressures in the pulmonary arteries and veins in the thorax—causes powerful sympathetic reflexes (initi-ated mainly by the arterial baroreceptors and other vascular stretch receptors).

These reflexes stimulate the sympathetic vasoconstric-tor system throughout the body, resulting in three important effects: (1) The arterioles constrict in most parts of the systemic circulation, thereby increasing the total peripheral resistance. (2) The veins and venous reservoirs constrict, thereby helping to main-tain adequate venous return despite diminished blood volume. (3) Heart activity increases markedly, some-times increasing the heart rate from the normal value of 72 beats/min to as high as 160 to 180 beats/min.

Value of the Sympathetic Nervous Reflexes. In theabsence of the sympathetic reflexes, only 15 to 20 per cent of the blood volume can be removed over a period of 30 minutes before a person dies; this is in contrast to a 30 to 40 per cent loss of blood volume that a person can sustain when the reflexes are intact. Therefore, the reflexes extend the amount of blood loss that can occur without causing death to about twice that which is possible in their absence.

Greater Effect of the Sympathetic Nervous Reflexes in Maintaining Arterial Pressure than in Maintaining Cardiac Output. Referring again to Figure 24–1, notethat the arterial pressure is maintained at or near normal levels in the hemorrhaging person longer than is the cardiac output. The reason for this is that the sympathetic reflexes are geared more for maintaining arterial pressure than for maintaining output. They increase the arterial pressure mainly by increasing the total peripheral resistance, which has no beneficial effect on cardiac output; however, the sympathetic con-striction of the veins is important to keep venous return and cardiac output from falling too much, in additionto their role in maintaining arterial pressure.

Especially interesting is the second plateau occur-ring at about 50 mm Hg in the arterial pressure curve of Figure 24–1. This results from activation of the central nervous system ischemic response, which causes extreme stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system when the brain begins to suffer from lack of oxygen or from excess buildup of carbon dioxide. This effect of the central nervous system ischemic response can be called the “last-ditch stand” of the sympathetic reflexes in their attempt to keep the arterial pressure from falling too low.

Protection of Coronary and Cerebral Blood Flow by the Reflexes. A special value of the maintenanceof normal arterial pressure even in the presence of decreasing cardiac output is protection of blood flow through the coronary and cerebral circulatory systems.

The sympathetic stimulation does not cause significant constriction of either the cerebral or the cardiac vessels. In addition, in both these vascular beds, local blood flow autoregulation is excellent, which prevents moderate decreases in arterial pressure from signifi-cantly decreasing their blood flows. Therefore, blood flow through the heart and brain is maintained essen-tially at normal levels as long as the arterial pressure does not fall below about 70 mm Hg, despite the fact that blood flow in some other areas of the body might be decreased to as little as one third to one quarter normal by this time because of vasoconstriction.

Related Topics