Chapter: Psychology: Thinking

Reasoning: Faulty Logic

Faulty Logic

When people fall prey to

confirmation bias, their thinking seems illogical: “If I know how to pick

winners, then I should win my bets. In fact, though, I lose my bets. Therefore,

I know how to pick winners.” But could this be? Are people really this

illog-ical in their reasoning? One way to find out is by asking people to solve

simple prob-lems in logic—for example, problems involving syllogisms.

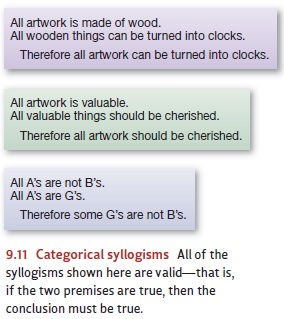

A syllogism contains two premises

and a conclusion, and the question is whether the conclusion follows logically

from the premises; if it does follow, we say that the conclu-sion is valid. Figure 9.11 offers several

examples; and let’s be clear that in these (or any) syllogisms, the validity of

the conclusion depends only on the premises. It doesn’t mat-ter if the

conclusion is plausible or not, in light of other things you know about the

world. It also doesn’t matter if the premises happen to be true or not. All

that matters is the relationship between the premises and the conclusion—and,

in particular, whether the conclusion must be true if the premises are true.

Syllogisms seem straightforward,

and so it’s disheartening that people make an enormous number of errors in

evaluating them. To be sure, some syllogisms are easier than others—and so

participants are more accurate, for example, if a syllogism is set in concrete

terms rather than abstract symbols. Still, across all the syllogisms, mistakes

are frequent, and error rates are sometimes as high as 70 or 80% (Gilhooly,

1988).

What produces this high error

rate? Despite careful instructions and considerable coaching, many participants

seem not to understand what syllogistic reasoning requires. Specifically, they

seem not to get the fact that they’re supposed to focus only on the

relationship between the premises and conclusion. They focus instead on whether

the conclusion seems plausible on its own—and if it is, they judge the

syllo-gism to be valid (Klauer, Musch, & Naumer, 2000). Thus, they’re more

likely to endorse the conclusion “Therefore all artwork should be cherished” in

Figure 9.11 than they are to endorse the conclusion “Therefore all artwork can

be turned into clocks.” Both of these conclusions are warranted by their

premises, but the first is plausible and so more likely to be accepted as

valid.

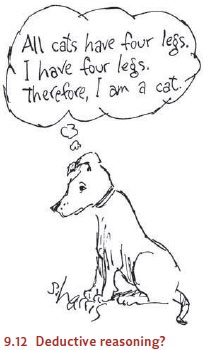

In some ways, this reliance on

plausibility is a sensible strategy. Participants are doing their best to

assess the syllogisms’ conclusions based on all they know (cf. Evans &

Feeney, 2004). At the same time, this strategy implies a profound

misunderstanding of the rules of logic (Figure 9.12). With this strategy,

people are willing to endorse a bad argument if it happens to lead to conclusions

they already believe are true, and they’re willing to reject a good argument if

it leads to conclusions they already believe are false.

Related Topics