Chapter: Basic & Clinical Pharmacology : Drugs Used in the Treatment of Gastrointestinal Diseases

Proton Pump Inhibitors

PROTON PUMP INHIBITORS

Since their introduction in the late 1980s,

these efficacious acid inhibitory agents have assumed the major role for the

treatment of acid-peptic disorders. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are now among

the most widely prescribed drugs worldwide due to their outstanding efficacy

and safety.

Chemistry & Pharmacokinetics

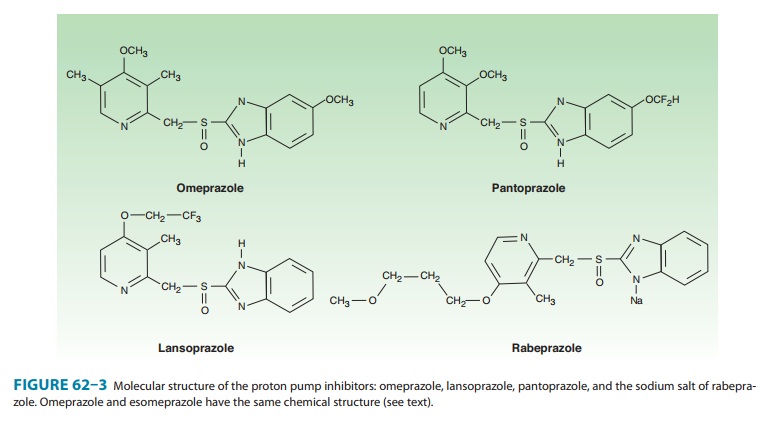

Six proton pump inhibitors are available for

clinical use: omepra-zole, esomeprazole,

lansoprazole, dexlansoprazole, rabepra-zole, and pantoprazole. All are substituted benzimidazoles thatresemble H2 antagonists in

structure (Figure 62–3) but have a completely different mechanism of action.

Omeprazole and lanso-prazole are racemic mixtures of R- and S-isomers.

Esomeprazole is the S-isomer of

omeprazole and dexlansoprazole the R-isomer

of lansoprazole. All are available in oral formulations. Esomeprazole and

pantoprazole are also available in intravenous formulations (Table 62–2).

Proton pump inhibitors are administered as

inactive prodrugs. To protect the acid-labile prodrug from rapid destruction

within the gastric lumen, oral products are formulated for delayed release as

acid-resistant, enteric-coated capsules or tablets. After passing through the

stomach into the alkaline intestinal lumen, the enteric

For children or patients with dysphagia

or enteral feeding tubes, capsule formula-tions (but not tablets) may be opened

and the microgranules mixed with apple or orange juice or mixed with soft foods

(eg, applesauce). Lansoprazole is also available as a tablet formulation that

disintegrates in the mouth, or it may be mixed with water and administered via

oral syringe or enteral tube. Omeprazole is also available as a powder

formulation (capsule or packet) that contains sodium bicarbonate (1100–1680 mg

NaHCO3; 304–460 mg of sodium) to protect

the naked (non-enteric-coated) drug from acid degradation. When administered on

an empty stomach by mouth or enteral tube, this “immediate-release” suspension

results in rapid omeprazole absorption (Tmax< 30

minutes) and onset of acid inhibition.

The proton

pump inhibitors are lipophilic weak bases (pKa

4–5) and after intestinal absorption diffuse readily across lipid membranes into

acidified compartments (eg, the parietal cell canaliculus). The prodrug rapidly

becomes protonated within the canaliculus and is concentrated more than

1000-fold by Henderson-Hasselbalch trapping . There, it rapidly undergoes a

molecular conversion to the active form, a reactive thiophilic sulfenamide

cation, which forms a covalent disulfide bond with the H+/K+-ATPase, irreversibly

inactivating the enzyme.

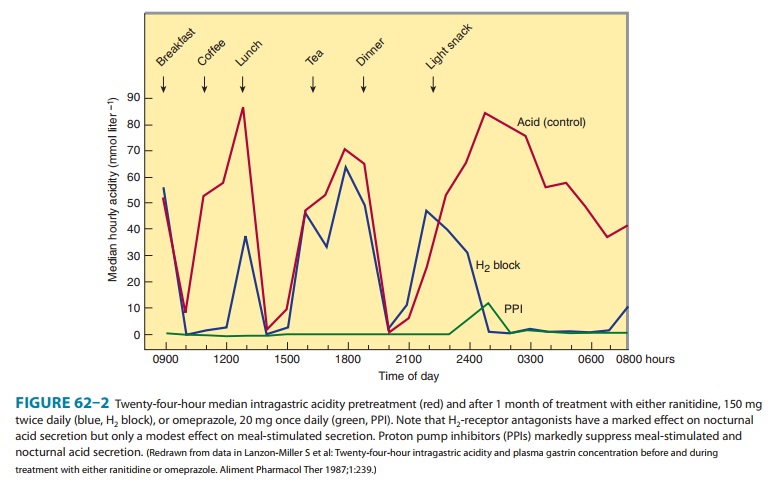

The pharmacokinetics of available proton pump inhibitors are shown in Table 62–2. Immediate-release omeprazole has a faster onset of acid inhibition than other oral formulations. Although differences in pharmacokinetic profiles may affect speed of onset and duration of acid inhibition in the first few days of therapy, they are of little clinical importance with continued daily admin-istration. The bioavailability of all agents is decreased approxi-mately 50% by food; hence, the drugs should be administered on an empty stomach.

In a fasting state, only 10%

of proton pumps are actively secreting acid and susceptible to inhibition.

Proton pump inhibitors should be administered approximately 1 hour before a

meal (usually breakfast), so that the peak serum concen-tration coincides with

the maximal activity of proton pump secre-tion. The drugs have a short serum

half-life of about 1.5 hours, but acid inhibition lasts up to 24 hours owing to

the irreversible inactivation of the proton pump. At least 18 hours are

required for synthesis of new H+/K+-ATPase pump

molecules. Because not all proton pumps are inactivated with the first dose of

medication, up to 3–4 days of daily medication are required before the full

acid-inhibiting potential is reached. Similarly, after stopping the drug, it

takes 3–4 days for full acid secretion to return.

Proton pump inhibitors undergo rapid

first-pass and systemic hepatic metabolism and have negligible renal clearance.

Dose reduction is not needed for patients with renal insufficiency or mild to

moderate liver disease but should be considered in patients with severe liver

impairment. Although other proton pumps exist in the body, the H+/K+-ATPase appears to exist only in the parietal cell and is distinct

structurally and functionally from other H+-transporting enzymes.

The intravenous formulations of esomeprazole

and pantopra-zole have characteristics similar to those of the oral drugs. When

given to a fasting patient, they inactivate acid pumps that are actively

secreting, but they have no effect on pumps in quiescent, nonsecreting

vesicles. Because the half-life of a single injection of the intravenous

formulation is short, acid secretion returns several hours later as pumps move

from the tubulovesicles to the canali-cular surface. Thus, to provide maximal

inhibition during the first 24–48 hours of treatment, the intravenous

formulations must be given as a continuous infusion or as repeated bolus

injections. The optimal dosing of intravenous proton pump inhibitors to achieve

maximal blockade in fasting patients is not yet established.

From a pharmacokinetic perspective, proton

pump inhibitors are ideal drugs: they have a short serum half-life, they are

concen-trated and activated near their site of action, and they have a long

duration of action.

Pharmacodynamics

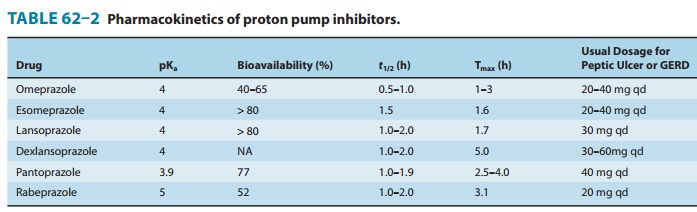

In contrast to H2 antagonists, proton pump inhibitors inhibit both fasting and meal-stimulated secretion because they block the final common pathway of acid secretion, the proton pump. In standard doses, proton pump inhibitors inhibit 90–98% of 24-hour acid secretion (Figure 62–2). When administered at equivalent doses, the different agents show little difference in clinical efficacy. In a crossover study of patients receiving long-term therapy with five proton pump inhibitors, the mean 24-hour intragastric pH varied from 3.3 (pantoprazole, 40 mg) to 4.0 (esomeprazole, 40 mg) and the mean number of hours the pH was higher than 4 varied from 10.1 (pantoprazole, 40 mg) to 14.0 (esomeprazole, 40 mg). Although dexlansoprazole has a delayed-release formulation that results in a longer Tmax and greater AUC than other proton pump inhibitors, it appears comparable to other agents in the ability to suppress acid secretion. This is because acid suppression is more dependent upon irreversible nactivation of the proton pump than the pharmacokinetics of different agents.

Clinical Uses

A. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

(GERD)

Proton pump inhibitors are the most effective

agents for the treat-ment of nonerosive and erosive reflux disease, esophageal

compli-cations of reflux disease (peptic stricture or Barrett’s esophagus), and

extraesophageal manifestations of reflux disease. Once-daily dosing provides

effective symptom relief and tissue healing in 85–90% of patients; up to 15% of

patients require twice-daily dosing.

GERD

symptoms recur in over 80% of patients within 6 months after discontinuation of

a proton pump inhibitor. For patients with erosive esophagitis or esophageal

complications, long-term daily maintenance therapy with a full-dose or

half-dose proton pump inhibitor is usually needed. Many patients with

nonerosive GERD may be treated successfully with intermittent courses of proton

pump inhibitors or H2

antagonists taken as needed (“on demand”) for recurrent symptoms.

In current

clinical practice, many patients with symptomatic GERD are treated empirically

with medications without prior endoscopy, ie, without knowledge of whether the

patient has ero-sive or nonerosive reflux disease. Empiric treatment with

proton pump inhibitors provides sustained symptomatic relief in 70–80% of

patients, compared with 50–60% with H2

antagonists. Because of recent cost reductions, proton pump inhibitors are

being used increasingly as first-line therapy for patients with symptomatic

GERD.

Sustained acid suppression with twice-daily

proton pump inhibitors for at least 3 months is used to treat extraesophageal

complications of reflux disease (asthma, chronic cough, laryngitis, and

noncardiac chest pain).

B. Peptic Ulcer Disease

Compared

with H2 antagonists, proton pump

inhibitors afford more rapid symptom relief and faster ulcer healing for

duodenal ulcers and, to a lesser extent, gastric ulcers. All the pump

inhibi-tors heal more than 90% of duodenal ulcers within 4 weeks and a similar

percentage of gastric ulcers within 6–8 weeks.

1.H

pylori-associated ulcers— ForH pylori-associated ulcers,there are two therapeutic goals: to heal

the ulcer and to eradicate the organism. The most effective regimens for H pylori eradication are combinations of

two antibiotics and a proton pump inhibitor. Proton pump inhibitors promote

eradication of H pylori through

several mechanisms: direct antimicrobial properties (minor) and—by raising

intragastric pH—lowering the minimal inhibi-tory concentrations of antibiotics

against H pylori. The best treat-ment

regimen consists of a 14-day regimen of “triple therapy”: a proton pump

inhibitor twice daily; clarithromycin, 500 mg twice daily; and either

amoxicillin, 1 g twice daily, or metronidazole,mg twice daily. After completion

of triple therapy, the proton pump inhibitor should be continued once daily for

a total of 4–6 weeks to ensure complete ulcer healing. Alternatively, 10 daysof

“sequential treatment” consisting on days 1–5 of a proton pump inhibitor twice

daily plus amoxicillin, 1 g twice daily, and followed on days 6–10 by five

additional days of a proton pump inhibitor twice daily, plus clarithromycin,

500 mg twice daily, and tinidazole, 500 mg twice daily, has been shown to be a

highly effective treatment regimen.

2. NSAID-associated

ulcers—For

patients with ulcers causedby aspirin or other NSAIDs, either H2 antagonists or proton

pump inhibitors provide rapid ulcer healing so long as the NSAID is

discontinued; however continued use of the NSAID impairs ulcer healing. In

patients with NSAID-induced ulcers who require continued NSAID therapy,

treatment with a once- or twice-daily proton pump inhibitor more reliably

promotes ulcer healing.

Asymptomatic peptic ulceration develops in

10–20% of people taking frequent NSAIDs, and ulcer-related complications

(bleed-ing, perforation) develop in 1–2% of persons per year. Proton pump

inhibitors taken once daily are effective in reducing the incidence of ulcers

and ulcer complications in patients taking aspirin or other NSAIDs.

3.

Prevention of rebleeding from peptic ulcers—In patientswith acute gastrointestinal

bleeding due to peptic ulcers, the risk of rebleeding from ulcers that have a

visible vessel or adherent clot is increased. Rebleeding of this subset of

high-risk ulcers is reduced significantly with proton pump inhibitors

administered for 3–5 days either as high-dose oral therapy (eg, omeprazole, 40

mg orally twice daily) or as a continuous intravenous infusion. It is believed

that an intragastric pH higher than 6 may enhance coagulation and platelet

aggregation. The optimal dose of intravenous proton pump inhibitor needed to

achieve and maintain this level of near-complete acid inhibition is unknown;

however, initial bolus administration of esomeprazole or pantoprazole (80 mg)

followed by constant infusion (8 mg/h) is commonly recommended.

C. Nonulcer Dyspepsia

Proton pump inhibitors have modest efficacy

for treatment of non-ulcer dyspepsia, benefiting 10–20% more patients than

placebo. Despite their use for this indication, superiority to H2 antagonists (or even

placebo) has not been conclusively demonstrated.

D. Prevention of Stress-Related Mucosal Bleeding

As

discussed previously (see H2-Receptor

Antagonists) proton pump inhibitors (given orally, by nasogastric tube, or by

intrave-nous infusions) may be administered to reduce the risk of clini-cally

significant stress-related mucosal bleeding in critically ill patients. The

only proton pump inhibitor approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

for this indication is an oral immediate-release omeprazole formulation, which

is administered by nasogastric tube twice daily on the first day, then once

daily. For patients with nasoenteric tubes, immediate-release omeprazole may be

preferred to intravenous H2

antagonists or other proton pump inhibitors because of comparable efficacy,

lower cost, and ease of administration.

For patients without a nasoenteric tube or

with significant ileus, intravenous H2 antagonists are preferred to intravenous

proton pump inhibitors because of their proven efficacy and lower cost.

Although proton pump inhibitors are increasingly used, there are no controlled

trials demonstrating efficacy or optimal dosing.

E. Gastrinoma and Other Hypersecretory Conditions

Patients with isolated gastrinomas are best

treated with surgical resection. In patients with metastatic or unresectable

gastrinomas, massive acid hypersecretion results in peptic ulceration, erosive

esophagitis, and malabsorption. Previously, these patients required vagotomy

and extraordinarily high doses of H2 antagonists, which still resulted in

suboptimal acid suppression. With proton pump inhibitors, excellent acid

suppression can be achieved in all patients. Dosage is titrated to reduce basal

acid output to less than 5–10 mEq/h. Typical doses of omeprazole are 60–120

mg/d.

Adverse Effects

A. General

Proton pump inhibitors are extremely safe.

Diarrhea, headache, and abdominal pain are reported in 1–5% of patients,

although the frequency of these events is only slightly increased compared with

placebo. Increasing cases of acute interstitial nephritis have been reported.

Proton pump inhibitors do not have teratogenicity in animal models; however,

safety during pregnancy has not been established.

B. Nutrition

Acid is

important in releasing vitamin B12

from food. A minor reduction in oral cyanocobalamin absorption occurs during

pro-ton pump inhibition, potentially leading to subnormal B12

levels with prolonged therapy. Acid also promotes absorption of food-bound

minerals (non-heme iron, insoluble calcium salts, magne-sium). Several

case-control studies have suggested a modest increase in the risk of hip

fracture in patients taking proton pump inhibitors over a long term compared

with matched controls. Although a causal relationship is unproven, proton pump

inhibi-tors may reduce calcium absorption or inhibit osteoclast function.

Pending further studies, patients who require long-term proton pump

inhibitors—especially those with risk factors for osteoporo-sis—should have

monitoring of bone density and should be pro-vided calcium supplements. Cases

of severe, life-threatening hypomagnesemia with secondary hypocalcemia due to

proton pump inhibitors have been reported; however, the mechanism of action is

unknown.

C. Respiratory and Enteric Infections

Gastric

acid is an important barrier to colonization and infection of the stomach and

intestine from ingested bacteria. Increases in gastric bacterial concentrations

are detected in patients taking proton pump inhibitors, which is of unknown

clinical signifi-cance. Some studies have reported an increased risk of both

com-munity-acquired respiratory infections and nosocomial pneumonia among

patients taking proton pump inhibitors.

There is a

2- to 3-fold increased risk for hospital- and community-acquired Clostridium difficile infection in

patients taking proton pump inhibitors. There also is a small increased risk of

other enteric infections (eg, Salmonella,

Shigella, E coli, Campylobacter), which should be considered particularly

when traveling in under-developed countries.

D. Potential Problems Due to Increased Serum Gastrin

Gastrin levels are regulated by intragastric

acidity. Acid suppres-sion alters normal feedback inhibition so that median

serum gas-trin levels rise 1.5- to 2-fold in patients taking proton pump

inhibitors. Although gastrin levels remain within normal limits in most

patients, they exceed 500 pg/mL (normal, < 100 pg/mL) in 3%.

Upon stopping the drug, the levels normalize within 4 weeks. The rise in serum

gastrin levels may stimulate hyperplasia of ECL and parietal cells, which may

cause transient rebound acid hyper-secretion with increased dyspepsia or

heartburn after drug discon-tinuation, which abate within 2–4 weeks after

gastrin and acid secretion normalize. In female rats given proton pump

inhibitors for prolonged periods, hypergastrinemia caused gastric carcinoid

tumors that developed in areas of ECL hyperplasia. Although humans who take

proton pump inhibitors for a long time also may exhibit ECL hyperplasia,

carcinoid tumor formation has not been documented. At present, routine

monitoring of serum gas-trin levels is not recommended in patients receiving

prolonged proton pump inhibitor therapy.

E. Other Potential Problems Due to Decreased Gastric Acidity

Among patients infected with H pylori, long-term acid suppres-sion

leads to increased chronic inflammation in the gastric body and decreased

inflammation in the antrum. Concerns have been raised that increased gastric

inflammation may accelerate gastric gland atrophy (atrophic gastritis) and intestinal

metaplasia— known risk factors for gastric adenocarcinoma. A special FDA

Gastrointestinal Advisory Committee concluded that there is no evidence that

prolonged proton pump inhibitor therapy produces the kind of atrophic gastritis

(multifocal atrophic gastritis) or intestinal metaplasia that is associated

with increased risk of ade-nocarcinoma. Routine testing for H pylori is not recommended in patients

who require long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy. Long-term proton pump

inhibitor therapy is associated with the development of small benign gastric

fundic-gland polyps in a small number of patients, which may disappear after

stopping the drug and are of uncertain clinical significance.

Drug Interactions

Decreased gastric acidity may alter absorption

of drugs for which intragastric acidity affects drug bioavailability, eg,

ketoconazole, itraconazole, digoxin, and atazanavir. All proton pump inhibitors

are metabolized by hepatic P450 cytochromes, including CYP2C19 and CYP3A4.

Because of the short half-lives of proton pump inhibitors, clinically

significant drug interactions are rare. Omeprazole may inhibit the metabolism

of warfarin, diazepam, and phenytoin. Esomeprazole also may decrease metabolism

ofdiazepam. Lansoprazole may enhance clearance of theophyl-line. Rabeprazole

and pantoprazole have no significant drug interactions.

The FDA has

issued a warning about a potentially important adverse interaction between

clopidogrel and proton pump inhibi-tors. Clopidogrel is a prodrug that requires

activation by the hepatic P450 CYP2C19 isoenzyme, which also is involved to

varying degrees in the metabolism of proton pump inhibitors (especially

omeprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, and dexlanso-prazole). Thus, proton

pump inhibitors could reduce clopidogrel activation (and its antiplatelet

action) in some patients. Several large retrospective studies have reported an

increased incidence of serious cardiovascular events in patients taking

clopidogrel and a proton pump inhibitor. In contrast, three smaller prospective

randomized trials have not detected an increased risk. Pending further studies,

proton pump inhibitors should be prescribed to patients taking clopidogrel only

if they have an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding or require them for

chronic gastro-esophageal reflux or peptic ulcer disease, in which case agents

with minimal CYP2C19 inhibition (pantoprazole or rabeprazole) are preferred.

Related Topics