Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Upper or Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction

Peritoneal Dialysis

PERITONEAL

DIALYSIS

The goals of peritoneal dialysis are to remove toxic substances and metabolic wastes and to re-establish normal fluid and electrolyte balance. Peritoneal dialysis may be the treatment of choice for pa-tients with renal failure who are unable or unwilling to undergo hemodialysis or renal transplantation. Patients who are suscepti-ble to the rapid fluid, electrolyte, and metabolic changes that occur during hemodialysis experience fewer of these problems with the slower rate of peritoneal dialysis. Therefore, patients with diabetes or cardiovascular disease, many older patients, and those who may be at risk for adverse effects of systemic heparin are likely candidates for peritoneal dialysis. Additionally, severe hypertension, heart failure, and pulmonary edema not responsive to usual treatment regimens have been successfully treated with peritoneal dialysis.

Peritoneal

dialysis can be performed using several different ap-proaches: acute,

intermittent peritoneal dialysis; continuous

am-bulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD); and continuous cyclic peritoneal dialysis (CCPD). These three methods

are discussed later. As with other forms of treatment, the deci-sion to begin

peritoneal dialysis is made by the patient and fam-ily in consultation with the

physician.

Although

specific patient populations do benefit from peri-toneal dialysis, it is not as

efficient as hemodialysis (Lindsay & Kortas, 2001). Because cardiovascular

disease is the cause of death in half of all patients with ESRD, the adequacy

of dialysis must be defined, in part, by its potential to reduce cardiovascular

dis-ease. Blood pressure, volume, left ventricular hypertrophy, and

dyslipidemias are the major causes of morbidity and mortality in patients

undergoing peritoneal dialysis (Chatoth, Golper & Gokal, 1999).

Underlying Principles

In

peritoneal dialysis, the peritoneum, a serous membrane that covers the

abdominal organs and lines the abdominal wall, serves as the semipermeable

membrane. The surface of the peritoneum constitutes a body surface area of about

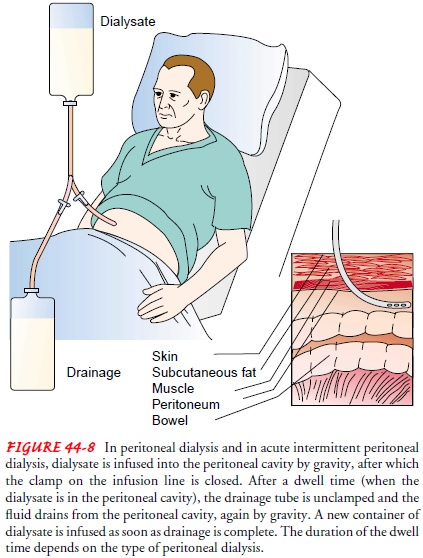

22,000 cm2. Sterile dialysate

fluid is introduced into the peritoneal cavity through an abdominal catheter at

intervals (Fig. 44-8). Urea and creatinine, metabolic end products normally

excreted by the kidneys, are cleared from the blood by diffusion and ossmosis

as waste products move from an area of higher concentration (the peritoneal

blood supply) to an area of lower concentration (the peritoneal cavity) across

a semipermeable membrane (the peritoneal membrane). Urea is cleared at a rate

of 15 to 20 mL/min, whereas creatinine is removed at a slower rate. It usually

takes 36 to 48 hours to achieve with peritoneal dialysis what hemodialysis

accomplishes in 6 to 8 hours. Ultrafiltration (water removal) occurs in

peritoneal dialysis through an osmotic gradient created by using a dialysate

fluid with a higher glucose concentration.

Procedure

The patient undergoing peritoneal dialysis may be acutely ill, thus requiring short-term treatment to correct severe distur-bances in fluid and electrolyte status, or may have chronic renal failure and need to receive ongoing treatments.

PREPARING THE PATIENT

The

nurse’s preparation of the patient and family for peritoneal dialysis depends

on the patient’s physical and psychological sta-tus, level of alertness,

previous experience with dialysis, and un-derstanding of and familiarity with

the procedure.

The

nurse explains the procedure to the patient and obtains signed consent for it.

Baseline vital signs, weight, and serum elec-trolyte levels are recorded. The

patient is encouraged to empty the bladder and bowel to reduce the risk of

puncturing internal organs. The nurse also assesses the patient’s anxiety about

the pro-cedure and provides support and instruction. Broad-spectrum antibiotic

agents may be administered to prevent infection. If the peritoneal catheter is

to be inserted in the operating room, this is explained to the patient and

family.

PREPARING THE EQUIPMENT

In

addition to assembling the equipment for peritoneal dialysis, the nurse

consults with the physician to determine the concen-tration of dialysate to be

used and the medications to be added to it. Heparin may be added to prevent

blood clotting and resultant occlusion of the peritoneal catheter. Potassium

chloride may be prescribed to prevent hypokalemia. Antibiotics may be added to

treat peritonitis. Insulin may be added for diabetic patients; a

larger-than-normal dose may be needed, however, because about 10% of the

insulin binds to the dialysate container. All medica-tions are added

immediately before the solution is instilled. Asep-tic technique is crucial.

Before

medications are added, the dialysate is warmed to body temperature to prevent

patient discomfort and abdominal pain and to dilate the vessels of the

peritoneum to increase urea clearance. Solutions that are too cold cause pain

and vasoconstriction and reduce clearance. Solutions that are too hot burn the

peritoneum. Dry heating is recommended (heating cabinet, incubator, or heat-ing

pad). Microwave heating of the fluid is not recommended be-cause of the danger

of burning the peritoneum.

Immediately

before initiating dialysis, the nurse assembles the administration set and

tubing. The tubing is filled with the pre-pared dialysate to reduce the amount

of air entering the catheter and peritoneal cavity, which could increase

abdominal discom-fort and interfere with instillation and drainage of the

fluid.

INSERTING THE CATHETER

Ideally,

the peritoneal catheter is inserted in the operating room to maintain surgical

asepsis and minimize the risk of contamina-tion. In some circumstances,

however, the physician inserts the catheter at the bedside under strict

asepsis.

A

rigid stylet catheter is inserted for acute peritoneal dialysis use only.

Before the procedure, the skin is prepared with a local antiseptic to reduce

skin bacteria and the risk of contamination and infection. The physician

anesthetizes the site with a local anesthetic agent before making a small

incision or stab wound in the lower abdomen, 3 to 5 cm below the umbilicus.

Because this area is relatively free from large blood vessels, little bleeding

oc-curs. A trocar is used to puncture the peritoneum as the patient tightens

the abdominal muscles by raising the head. The catheter is threaded through the

trocar and positioned. Previously pre-pared dialysate is infused into the

peritoneal cavity, pushing the omentum (peritoneal lining extending from the

abdominal or-gans) away from the catheter. The physician may then secure the

catheter with a purse-string suture and apply antibacterial oint-ment and a

sterile dressing over the site.

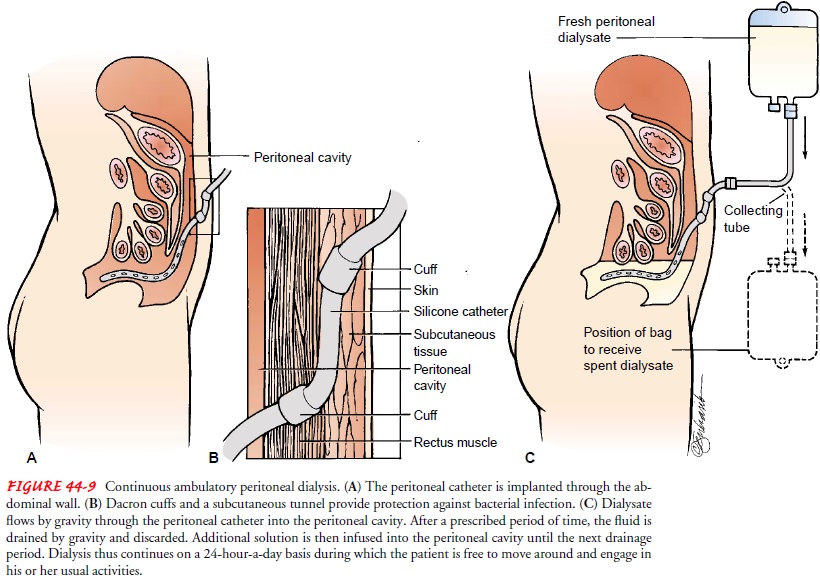

Catheters

for long-term use (Tenckhoff, Swan, Cruz) are usu-ally made of silicone and are

radiopaque to permit visualization on x-ray. These catheters have three

sections: (1) an intraperi-toneal section, with numerous openings and an open

tip to let dialysate flow freely; (2) a subcutaneous section that passes from

the peritoneal membrane and tunnels through muscle and sub-cutaneous fat to the

skin; and (3) an external section for connec-tion to the dialysate system. Most

of these catheters have two cuffs, which are made of Dacron polyester. The

cuffs stabilize the catheter, limit movement, prevent leaks, and provide a

barrier against microorganisms. One cuff is placed just distal to the

peri-toneum, and the other cuff is placed subcutaneously. The subcu-taneous

tunnel (5 to 10 cm long) further protects against bacterial infection (Fig.

44-9).

PERFORMING THE EXCHANGE

Peritoneal

dialysis involves a series of exchanges or cycles. An ex-change is defined as

the infusion, dwell, and drainage of the dialysate. This cycle is repeated

throughout the course of the dial-ysis. The dialysate is infused by gravity

into the peritoneal cavity. A period of about 5 to 10 minutes is usually

required to infuse 2 L of fluid. The prescribed dwell, or equilibration, time

allows dif-fusion and osmosis to occur. Diffusion of small molecules, such as

urea and creatinine, peaks in the first 5 to 10 minutes of the dwell time. At

the end of the dwell time, the drainage portion of the exchange begins. The

tube is unclamped and the solution drains from the peritoneal cavity by gravity

through a closed sys-tem. Drainage is usually completed in 10 to 30 minutes.

The drainage fluid is normally colorless or straw-colored and should not be

cloudy. Bloody drainage may be seen in the first few ex-changes after insertion

of a new catheter but should not occur after that time. The entire exchange

(infusion, dwell time, and drainage) takes 1 to 4 hours, depending on the

prescribed dwell time. The number of cycles or exchanges and their frequency

are prescribed based on the patient’s physical status and acuity of illness.

The removal of excess water during peritoneal dialysis is achieved by using a hypertonic dialysate with a high dextrose con-centration that creates an osmotic gradient. Dextrose solutions of 1.5%, 2.5%, and 4.25% are available in several volumes, from 500 mL to 3,000 mL, allowing the dialysate selection to fit the patient’s tolerance, size, and physiologic needs. The higher the dex-trose concentration, the greater the osmotic gradient and the more water removed. Selection of the appropriate solution is based on the patient’s fluid status.

Complications of Peritoneal Dialysis

Peritoneal

dialysis is not without complications. Most are minor, but several, if

unattended, can have serious consequences.

PERITONITIS

Peritonitis (inflammation of the peritoneum) is the most

com-mon and most serious complication of peritoneal dialysis. The or-ganism

responsible for peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis is an important factor

in clinical outcome and the basis of treatment guidelines. There has been a

significant decrease in the rate of cases of peritonitis, from 1.37

episodes/patient-year in 1991 to 0.55 episodes/patient-year in 1998. Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis remain the

most common Gram-positiveorganisms responsible for peritonitis, although the

rates of each have decreased. Pseudomonas

aeruginosa, E. coli, and Klebsiella

species are the most common causes of Gram-negative peritonitis. Resistance to

antibacterial agents (ie, ciprofloxacin, methicillin) used in their treatment

increased dramatically from 1991 to 1998 (Zelenitsky et al., 2000).

Peritonitis

is characterized by cloudy dialysate drainage, dif-fuse abdominal pain, and

rebound tenderness. Hypotension and other signs of shock may occur if S. aureus is the responsible or-ganism.

The patient with peritonitis may be treated as an inpa-tient or outpatient

(most common), depending on the severity of the infection and the patient’s

clinical status. Initially, one to three rapid exchanges with a 1.5% dextrose

solution without added medications are completed to wash out mediators of

in-flammation and to reduce abdominal pain. Drainage fluid is ex-amined for

cell count, and Gram’s stain and culture are used to identify the organism and

guide treatment. Antibiotic agents (aminoglycosides or cephalosporins) are

usually added to subse-quent exchanges until the Gram’s stain or culture

results are avail-able for appropriate antibiotic determination.

Intraperitoneal administration of antibiotics is as effective as intravenous

admin-istration. Antibiotic therapy continues for 10 to 14 days. Careful

calculation of the antibiotic dosage helps prevent nephrotoxicity and further

compromise of renal function.

Heparin

(500 to 1,000 U/L) may be added to the dialysate to prevent fibrin clot

formation; oral administration of low-dose warfarin (Coumadin) is also

effective in decreasing coagulation factors and preventing thrombosis without

increasing the risk of bleeding (Kim, Lee, Park et al., 2001).

Peritonitis

that is unresolved after 4 days of appropriate ther-apy necessitates catheter

removal. The patient is maintained on hemodialysis for about 1 month before a

new catheter is inserted. In patients with fungal peritonitis, the peritoneal

catheter must be removed if there is no response to therapy in 4 to 7 days.

Tun-nel infections and fecal peritonitis also necessitate catheter re-moval.

Systemic antibiotics should continue for 5 to 7 days after catheter removal.

Regardless

of which organism causes peritonitis, the patient with peritonitis loses large

amounts of protein through the peri-toneum. Acute malnutrition and delayed

healing may result. Therefore, attention must be given to detecting and

promptly treating the infections.

LEAKAGE

Leakage

of dialysate through the catheter site may occur imme-diately after the

catheter is inserted. Usually, the leak stops spon-taneously if dialysis is

withheld for several days to give the incision and exit site time to heal.

During this time, it is important to reduce factors that might delay healing,

such as undue abdominal muscle activity and straining during bowel movement.

Leakage through the exit site or into the abdominal wall can occur for months

or years after catheter placement. In many cases, leakage can be avoided by

using small volumes (100 to 200 mL) of dialysate, gradually increasing the volume

up to 2,000 mL.

BLEEDING

A

bloody effluent (drainage) may be observed occasionally, espe-cially in young,

menstruating women. (The hypertonic fluid pulls blood from the uterus, through

the opening in the fallopian tubes, and into the peritoneal cavity.) Bleeding

is common during the first few exchanges after a new catheter insertion because

some blood exists in the abdominal cavity from the procedure. In many cases, no

cause can be found for the bleeding, although catheter displacement from the

pelvis has occasionally been associated with bleeding. Some patients have had

bloody effluent after an enema or from minor trauma. Invariably, bleeding stops

in 1 to 2 days and requires no specific intervention. More frequent exchanges

during this time may be necessary to prevent blood clots from obstructing the

catheter.

LONG-TERM COMPLICATIONS

Hypertriglyceridemia

is common in patients undergoing long-term peritoneal dialysis, suggesting that

this therapy may accelerate ath-erogenesis. Despite this, the use of

cardioprotective medications is relatively low, and many patients have

suboptimal blood pres-sure control. Given the high burden of disease in these

patients, beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors should be

used to control hypertension or protect the heart; the use of aspirin and

statins should be considered. In general, health care providers need to be

better educated in this area of dialysis man-agement (Tonelli et al., 2001).

Other

complications that may occur with long-term peri-toneal dialysis include

abdominal hernias (incisional, inguinal, diaphragmatic, and umbilical),

probably resulting from continu-ously increased intra-abdominal pressure. The

persistently ele-vated intra-abdominal pressure also aggravates symptoms of

hiatal hernia and hemorrhoids. Low back pain and anorexia from fluid in the

abdomen and a constant sweet taste related to glucose absorption may also

occur.

Mechanical

problems occasionally occur and may interfere with instillation or drainage of

the dialysate. Formation of clots in the peritoneal catheter and constipation

are factors that may contribute to these problems.

Acute Intermittent Peritoneal Dialysis

Indications

for acute intermittent peritoneal dialysis, a variation of peritoneal dialysis,

include uremic signs and symptoms (nau-sea, vomiting, fatigue, altered mental

status), fluid overload, aci-dosis, and hyperkalemia. Although peritoneal

dialysis is not as efficient as hemodialysis in removing solute and fluid, it

permits a more gradual change in the patient’s fluid volume status and in waste

product removal. Therefore, it may be the treatment of choice for the

hemodynamically unstable patient. It can be car-ried out manually (the nurse

warms, spikes, and hangs each con-tainer of dialysate) or by a cycler machine.

Exchange times range from 30 minutes to 2 hours. A common routine is hourly

ex-changes consisting of a 10-minute infusion, a 30-minute dwell time, and a

20-minute drain time.

Maintaining the peritoneal dialysis cycle is

a nursing respon-sibility. Strict aseptic technique is maintained when changing

so-lution containers and emptying drainage containers. Vital signs, weight,

intake and output, laboratory values, and patient status are frequently

monitored. The nurse uses a flow sheet to document each exchange and records

vital signs, dialysate concentration, med-ications added, exchange volume,

dwell time, dialysate fluid balance for the exchange (fluid lost or gained),

and cumulative fluid balance. The nurse also carefully assesses skin turgor and

mucous mem-branes to evaluate fluid status and monitor the patient for edema.

If the peritoneal fluid does not drain

properly, the nurse can fa-cilitate drainage by turning the patient from side

to side or raising the head of the bed. The catheter should never be pushed in.

Other measures to promote drainage include checking the patency of the catheter

by inspecting for kinks, closed clamps, or an air lock. The nurse always

monitors for complications, including peritonitis, bleeding, respiratory difficulty,

and leakage of peritoneal fluid. Ab-dominal girth may be measured periodically

to determine if the pa-tient is retaining large amounts of dialysis solution.

Additionally, the nurse must ensure that the peritoneal dialysis catheter

remains secure and that the dressing remains dry. Physical comfort mea-sures,

frequent turning, and skin care are provided. The patient and family are

educated about the procedure and are kept in-formed about progress (fluid loss,

weight loss, laboratory values). Emotional support and encouragement are given

to the patient and family during this stressful and uncertain time.

Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis

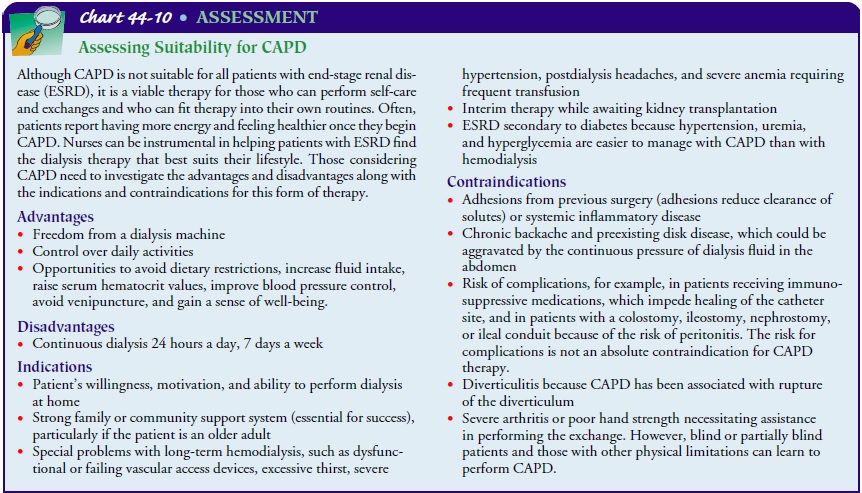

CAPD

is a form of dialysis used for many patients with ESRD. CAPD is performed at

home by the patient or a trained caregiver, who is usually a family member; the

procedure allows the patient reasonable freedom and control of daily activities

(Chart 44-10).

UNDERLYING PRINCIPLES

CAPD

works on the same principles as other forms of peritoneal dialysis: diffusion and

osmosis. Less extreme fluctuations in the patient’s laboratory results occur

with CAPD than with inter-mittent peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis because

the dialysis is constantly in progress. The serum electrolyte levels usually

remain in the normal range.

PROCEDURE

The

patient performs exchanges four or five times a day, 24 hours a day, 7 days a

week, at intervals scheduled throughout the day (before meals and bedtime).

After infusing the dialysate into the peritoneal cavity through the catheter (over

about 10 minutes), the patient can fold the bag and tuck it underneath the

clothing during the dwell time. This provides the patient with some free-dom

and reduces the number of connections and disconnections necessary at the

catheter end of the tubing, thereby reducing the risk of contamination and

peritonitis.

The longer the dwell time, the better the clearance of middle-sized molecules. It is thought that these molecules may be sig-nificant uremic toxins. At the end of the dwell time, the dialysate is drained from the peritoneal cavity by unfolding the empty bag, opening the clamp, and placing the bag lower than the ab-domen near the floor. This allows the peritoneal fluid to drain out by gravity. When drainage ends, the patient repeats the pro-cedure by spiking a new bag containing dialysate and infusing the solution into the peritoneal cavity. Other systems are avail-able that allow the catheter to be clamped, disconnected, and capped, thus allowing the patient freedom from wearing an empty dialysate bag. Before the next exchange, however, an empty drainage bag must be attached to permit drainage of the dwell solution.

COMPLICATIONS

To

reduce the risk of peritonitis, the patient takes meticulous care to avoid

contaminating the catheter, fluid, or tubing and acci-dentally disconnecting

the catheter from the tubing. The catheter is protected from manipulation, and

the catheter entry site is meticulously cared for according to a standardized

protocol.

Nursing Management

In

addition to the complications of peritoneal dialysis previously described,

patients who elect to use CAPD may experience al-tered body image because of

the abdominal catheter and the bag and tubing. Waist size increases from 1 to 2

inches (or more) with fluid in the abdomen. This affects clothing selection and

may make the patient feel “fat.” Body image may be so altered that pa-tients do

not want to look at or care for the catheter for days or weeks. The nurse may

arrange for the patient to talk with other patients who have adapted well to

CAPD. Although some pa-tients have no psychological problems with the

catheter—they think of it as their lifeline and as a life-sustaining

device—other patients feel they are doing exchanges all day long and have no free

time, particularly in the beginning. They may experience de-pression because

they feel overwhelmed with the responsibility of self-care.

Patients

undergoing CAPD may also experience altered sexu-ality patterns and sexual

dysfunction. The patient and partner may be reluctant to engage in sexual

activities, partly because of the catheter being psychologically “in the way”

of sexual perfor-mance. The peritoneal catheter, drainage bag, and about 2 L of

dialysate may interfere with the patient’s sexual function and body image as

well. Although these problems may resolve with time, some problems may warrant

special counseling. Questions by the nurse about concerns related to sexuality

and sexual function often provide the patient with a welcome opportunity to

dis-cuss these issues and a first step toward their resolution.

PROMOTING HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED CARE

Teaching Patients Self-Care.

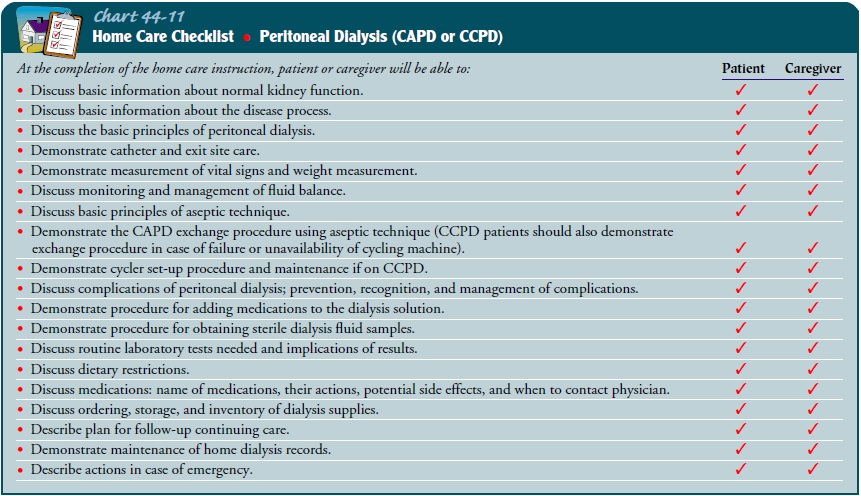

Patients are

taught as inpatients oroutpatients to perform CAPD once their condition is

medically stable. Training usually takes 5 days to 2 weeks. Patients are taught

according to their own learning ability and knowledge level, and only as much

at one time as they can handle without feeling uncomfortable or becoming

overwhelmed. Education topics for the patient and family who will be performing

peri-toneal dialysis at home are described in Chart 44-11.

Because

of protein loss with continuous peritoneal dialysis, pa-tients are instructed

to eat a high-protein, well-balanced diet. They are also encouraged to increase

their daily fiber intake to help prevent constipation, which can impede the

flow of dialysate into or out of the peritoneal cavity. Many patients gain 3 to

5 lb within a month of initiating CAPD, so they may be asked to limit their

carbohydrate intake to avoid excessive weight gain. Potas-sium, sodium, and

fluid restrictions are not usually needed. Patients commonly lose about 2 L of

fluid over and above the 8 L of dialysate infused into the abdomen during a

24-hour period, permitting a normal fluid intake even in an anephric patient (a

patient without kidneys). Greater small-solute clearances are associated with

better dietary intake and better nutrition (Wang, Sea, Ip et al., 2001).

Continuing Care.

Follow-up care through phone calls, visits tothe outpatient department, and continuing home care assists pa-tients in the transition to home and promotes their active partic-ipation in their own health care. Patients often depend on checking with the nurse to see if they are making the right choices about dialysate or control of blood pressure, or simply to discuss a problem.

Patients

may be seen by the CAPD team as outpatients once a month or more often if

needed. The exchange procedure is eval-uated at that time to see that strict

aseptic technique is being used. The CAPD nurse may change the tubing used to

instill the dialysate every 4 to 8 weeks. Long-life tubing now lasts up to 6

months before tubing changes are necessary. Infrequent tubing changes decrease

the risk of contamination. Blood chemistry val-ues are followed closely to make

certain the therapy is adequate for the patient.

If a

referral is made for home care, the home care nurse assesses the home

environment and suggests modifications to accommo-date the equipment and

facilities needed to carry out CAPD. In addition, the nurse assesses the

patient’s and family’s under-standing of CAPD and their use of safe technique

in performing CAPD. Additional assessments include checking for changes related

to renal disease, complications such as peritonitis, and treatment-related

problems such as heart failure, inadequate drainage, and weight gain or loss.

The nurse continues to reinforce and clarify teaching about CAPD and renal

disease and assesses the patient’s and family’s progress in coping with the

procedure. In addition, the patient is reminded about the need to participate

in health promotion activities and health screening.

Due to

the projected high numbers of elderly patients who will develop ESRD in the

future, the nursing home or extended-care facility will become an increasingly

important site for both rehabilitation and long-term management of patients

with renal failure. Although few such sites currently provide dialysis, highly

structured educational programs for personnel in these environ-ments by

nephrology staff will likely make these effective sites of care for patients

requiring continuous peritoneal dialysis (Carey, Chorney, Pherson et al.,

2001).

Continuous Cyclic Peritoneal Dialysis

CCPD

combines overnight intermittent peritoneal dialysis with a prolonged dwell time

during the day. The peritoneal catheter is connected to a cycler machine every

evening, and the patient re-ceives three to five 2-L exchanges during the

night. In the morn-ing, the patient caps off the catheter after infusing 1 to 2

L of fresh dialysate. This dialysate remains in the abdominal cavity until the

tubing is reattached to the cycler machine at bedtime. Because the machine is

very quiet, the patient can sleep. Moreover, the extra-long tubing allows the

patient to move and turn normally during sleep.

CCPD

has a lower infection rate than other forms of peri-toneal dialysis because

there are fewer opportunities for contam-ination with bag changes and tubing

disconnections. It also allows the patient to be free from exchanges throughout

the day, making it possible to work more freely and carry out activities of

daily living.

Related Topics