Chapter: Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases: Tissue Nematodes

Lymphatic Filariasis : Clinical Aspects

LYMPHATIC FILARIASIS : CLINICAL ASPECTS

MANIFESTATIONS

Individuals who enter endemic areas as adults and reside therein for months to years of-ten present with acute lymphadenitis, urticaria, eosinophilia, and elevated serum IgE levels; they seldom go on to develop lymphatic obstruction. A significant proportion of indigenous populations present with asymptomatic microfilaremia. Some of these sponta-neously clear their infection, and others go on to experience “filarial fevers” and lym-phadenitis 8 to 12 months after exposure. The fever is typically low grade; in more serious cases, however, temperatures as high as 40°C, chills, muscle pains, and other sys-temic manifestations may be seen. Classically, the lymphadenitis is first noted in the femoral area as an enlarged, red, tender lump. The inflammation spreads centrifugally down the lymphatic channels of the leg. The vessels become enlarged and tender, the overlying skin red and edematous. In Bancroftian filariasis, the lymphatic vessels of the testicle, epididymis, and spermatic cord are frequently involved, producing a painful or-chitis, epididymitis, and funiculitis; inflamed retroperitoneal vessels may simulate acute abdomen. Epitrochlear, axillary, and other lymphatic vessels are involved less frequently. The acute manifestations last a few days and resolve spontaneously, only to recur periodi-cally over a period of weeks to months. With repeated infection, permanent lymphatic ob-struction develops in the involved areas. Edema, ascites, pleural effusion, hydrocele, and joint effusion result. The lymphadenopathy persists and the palpably swollen lymphatic channels may rupture, producing an abscess or draining sinus. Rupture of intra-abdomi-nal vessels may give rise to chylous ascites or urine. In patients heavily and repeatedly in-fected over a period of decades, elephantiasis may develop. Such patients may continue to experience acute inflammatory episodes.

In southern India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Southeast Asia, and East Africa, an aberrant form of filariasis is seen. This form, termed tropical pulmonary eosinophilia, is characterized by an intense eosinophilia, elevated levels of IgE, high titers of filarial anti-bodies, the absence of microfilariae from the circulating blood, and a chronic clinical course marked by massive enlargement of the lymph nodes and spleen (children) or chronic cough, nocturnal bronchospasm, and pulmonary infiltrates (adults). Untreated, the disease may progress to pulmonary interstitial fibrosis. Microfilariae have been found in the tissues of such patients, and the clinical manifestations may be terminated with specific antifilarial treatment. It is believed that this syndrome is precipitated by the re-moval of circulating microfilariae by an IgG-dependent, cell-mediated immune reaction. Microfilariae are trapped in various tissue sites where they incite an eosinophilic inflam-matory response, granuloma formation, and fibrosis.

DIAGNOSIS

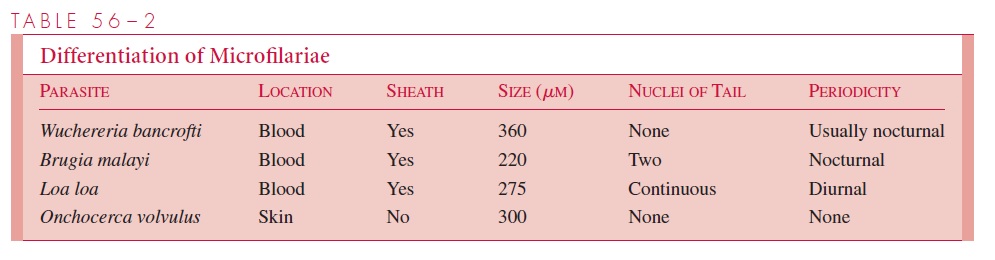

Eosinophilia is usually present during the acute inflammatory episodes, but definitive diagnosis requires the presence of microfilaria in the blood or lymphatic, ascitic, or pleural fluid. They are sought in Giemsa- or Wright-stained thick and thin smears. The major distinguishing features of these and other microfilariae are listed in Table 56–2. Because the appearance of the microfilariae is usually periodic, specimen collection must be properly timed. If this procedure proves difficult, the patient may be challenged with the antifilarial agent diethylcarbamazine (DEC). This drug stimulates the migration of the microfilariae from the pulmonary to the systemic circulation and enhances the possibility of their recovery. If the parasitemia is scant, the specimen may be concentrated before it is examined. Once found, the microfilariae must be differentiated from those produced by other species of filariae. A number of serologic tests have been employed for the diagnosis of microfilaremic disease, but until recently they have lacked adequate sensitivity and specificity; even the more recent tests are of little diagnostic significance in individuals indigenous to the endemic area, because many people have experienced a prior filarial infection. Circulating filarial antigens can be found in most microfilaremic patients and also in some seropositive amicrofilaremic individuals. Antigen detection may thus prove to be a specific indicator of active disease.

TREATMENT

DEC eliminates the microfilariae from the blood and kills or injures the adult worms, resulting in long-term suppression of the infection or parasitologic cure. Frequently the dying microfilariae stimulate an allergic reaction in the host. This response is occasionally severe, requiring the use of antihistamines and corticosteroids. The role of ivermectin in the treatment of lymphatic filariasis has not yet been established. Early studies have demonstrated a high level of effectiveness in clearing microfilaremia following the administration of a single dose. The tissue changes of elephantiasis are often irreversible,

but the enlargement of the extremities may be ameliorated with pressure bandages or plastic surgery. Control programs combine mosquito control with mass treatment of the entire population.

Related Topics