Chapter: Medicine and surgery: Genitourinary system

Introduction to testicular tumours - Genitourinary oncology

Introduction to testicular tumours

Definition

Tumours of the testis may be classified broadly into those arising from the germ-cell line and those arising from non-germ cells.

Incidence

Relatively uncommon (Ōł╝3ŌĆō6/100,000 per annum), but still the most common solid organ tumour in young men and increasing in recent years.

Age

Depends on type, peak 25ŌĆō40 years.

Sex

Males

Aetiology

Maldescent of the testis has a 10ŌĆō15-fold risk. Ten per cent of all testicular tumours develop in testes which are or were cryptorchid, some contralaterally. A family history is also a known risk factor as is infertility.

Pathophysiology

It is currently thought that the precursor of most germ cell tumours is intratubular germ cell neoplasia (sometimes called testicular carcinoma in situ), where the sem-iniferous tubules have atypical germ cells.

It appears that these atypical cells are formed early in gestation and may be influenced by events in utero. They then lie dormant, until puberty, when they spread non-invasively. In some individuals, they become malignant and either develop along the seminomatous or teratomatous line.

Classification

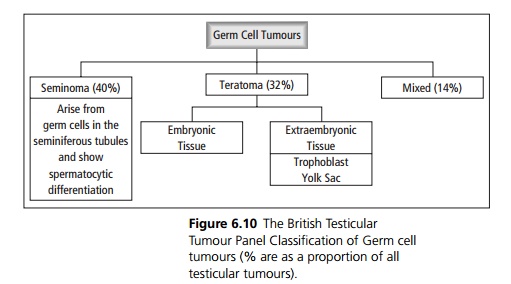

The main components of the testis are the germ cells (spermatogonia), the sex cords or seminiferous tubules (Sertoli cells) and stroma (Leydig cells). Germ cell tumours are the most common (90ŌĆō95%) testicular tumours. Germ cells are multipotent, i.e. can form many tissue types, as normally they are involved in reproduction and may form both embryonic and extraembryonic tissue. Therefore many different cell types may coexist in a germ cell tumour (see Fig. 6.10).

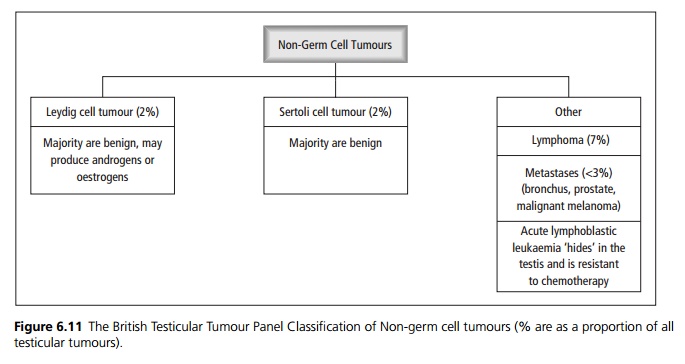

Nongerm cell tumours (see Fig. 6.11) include those arising from Sertoli and Leydig cells, of which only Ōł╝10% behave malignantly. Leydig cells normally produce testosterone, so Leydig cell tumours have the potential to produce steroid hormones at levels high enough to have systemic effects. Both Leydig cell and Sertoli cell tumours are uncommon. Other tumour types include lymphoma and metastases.

Clinical features

Testicular tumours usually present as slow, painless, smooth or irregular enlargement of a testis. A dull ache or dragging sensation in the lower abdomen or perineal/scrotal area is common. Acute pain occurs as a presenting feature in 10%, which may be attributed to trauma. Malignant tumours may present with metastatic disease before the primary is noticed and occasionally the tumour secretes hormones, causing symptoms such as gynaecomastia or precocious puberty.

On examination, there may be a concomitant hydrocele, making examination more difficult. The testes should be soft, smooth and mobile. Suspicious features include a hard, fixed mass, which may have smooth or irregular borders. If the mass transilluminates, this suggests a hydrocele, but it is not possible to exclude an underlying tumour without imaging. Associated gynaecomastia or lymphadenopathy should be looked for, as well as any evidence of metastases, e.g. to the liver.

Complications

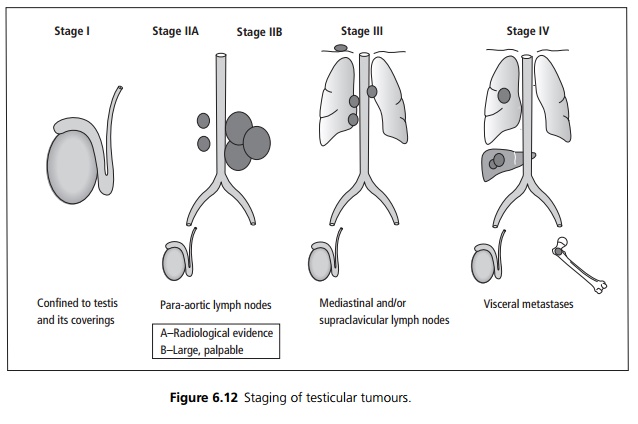

Spread is generally initially through the lymphatics, to iliac and paraaortic lymph nodes via the spermatic cord, then the mediastinal lymph nodes. Haematoge nous spread leads to metastases most commonly in the lungs, liver and bone.

Investigations

USS of the scrotum, especially if there is clinical doubt. Scrotal biopsy should be avoided, as this increases the risk of local spread and recurrence.

Other tests are directed at the staging of the tumour:

┬Ę Tumour markers ŌĆō Alphafetoprotein (╬▒FP), beta-human chorionic gonadotrophin (╬▓ŌĆōHCG) and lac-tate dehydrogenase (LDH) should be measured before treatment. These are raised in Ōł╝50% of patients and are useful for follow-up after treatment.

┬Ę A chest X-ray, CT abdomen and pelvis are generally needed. CT thorax/head may be indicated, if metastases to these areas are suspected.

┬Ę Staging is from I to IV see Fig. 6.12 but the TNM staging is also used.

Management

Testicular cancer is now one of the most curable solid organ tumours. Radical orchidectomy via an inguinal incision, with occlusion of the spermatic cord before mobilization (to reduce risk of intraoperative spread) is needed for all patients, to establish the histology, grade and staging (TNM). A testicular prosthesis may be placed at the time of surgery. Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection at the same time is indicated in low stage (I or IIA) disease, as CT scan is often falsely negative. However in higher stage disease, this may be postponed until the response to chemotherapy has been assessed. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy are both used in treatment. Seminomas are more radiosensitive.

Related Topics