Chapter: The Massage Connection ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY : Integumentary System

Inflammation and Healing on the surface of the skin

Inflammation and Healing

Inflammation—the reaction of living tissue to in-jury—is easily visualized on the surface of the skin. Inflammation and healing are detailed under this sys-tem, although these processes occur throughout the body. Although inflammation produces discomfort, it is beneficial and helps the body adapt to everyday stress. Inflammation helps heal wounds and prevents and combats infection. Inflammation depends on a healthy immune system.

COMMON CAUSES OF INFLAMMATION

Some common causes of inflammation are physical (burns; extreme cold, such as frostbite; trauma); chemical (chemical poisons, such as acid or organic poisons); infection (bacteria, viruses, fungi, or para-sites); and immunologic and other circumstances that lead to tissue damage, such as vascular or hor-monal disturbances. It is important to note that in-flammation is not always a result of infection. Condi-tions producing inflammation are denoted by adding the suffix, itis. For example, arthritis, inflammation of the joint; bursitis, inflammation of the bursa; ap- pendicitis, inflammation of the appendix; and neuri-tis, inflammation of the nerve.

CARDINAL SIGNS OF INFLAMMATION

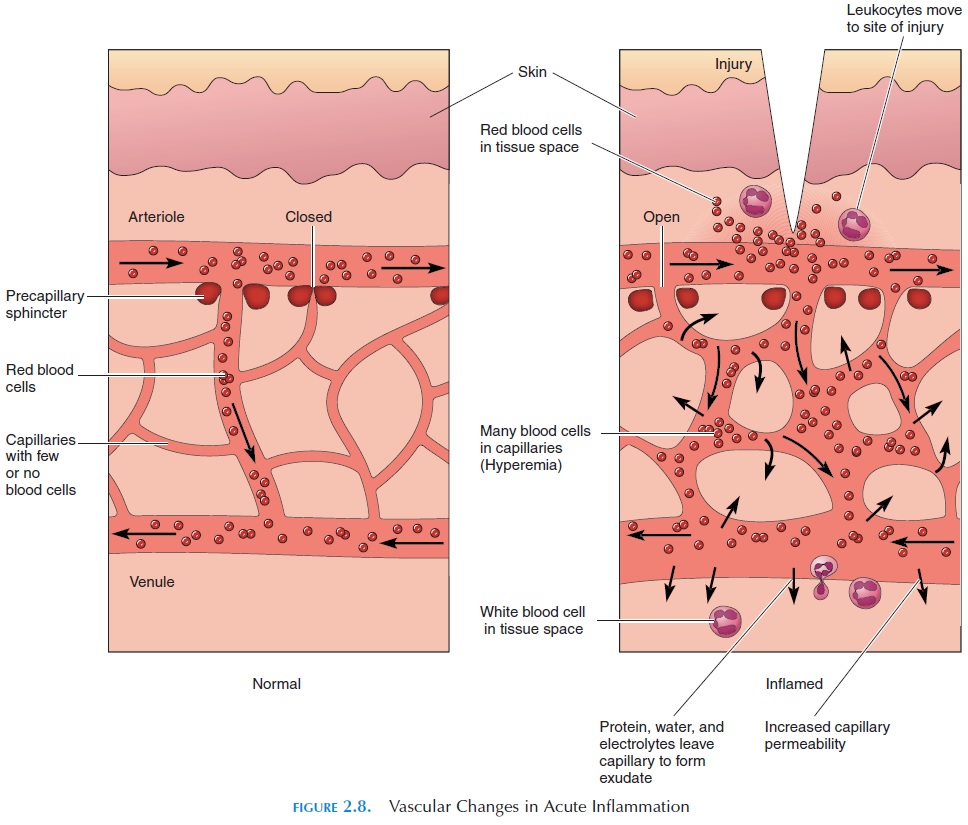

Despite the many causes of inflammation (see Figure 2.8), the sequence of physiologic changes that occur in the body are the same. If you scratch your forearm and observe the changes that occur, you will see the cardinal signs of inflammation, including redness, heat, swelling, pain, and loss of function.

These signs are caused by changes that occur at the microscopic level. When you scratch your fore-arm, you may notice immediate whitening of the skin. This reaction is a result of the constriction of blood vessels lying under the skin. Soon, the area ap-pears red (hyperemia). The blood vessels in the area dilate as a result of the liberation of chemicals by the injured tissue. If touched, the area feels warm. The warmth is a result of increased blood flow. Within minutes, swelling occurs along the line of injury (ex-udation). This swelling is a result of the fluid leakage from the capillaries, which have become more per-meable. The contents of the injured cells leak out and stimulate pain receptors in the vicinity, causing pain. The injured tissue may be unable to function prop-erly, partly because of pain.

These signs help control the effects of the injurious agent. The fluid that leaks out and the increased blood flow dilute the toxins that are produced. The pain alerts the individual to take remedial measures. The changes that occur with injury also stimulate clotting, reducing blood loss and containing the tox-ins within the local area.

Role of White Blood Cells

In inflammation, together with changes in the blood vessels, the white blood cells are triggered into ac-tion. Immediately after the injury, the white blood cells accumulate along the blood vessel walls, re-ferred to as margination or pavementing of white blood cells. Attracted by the chemicals liberated by the injured tissue, they squeeze through the widened gap between the cells of the capillary wall. This stage is known as the emigration of white blood cells. The white cells then move to the injured region. The process by which the white cells are attracted to the tissue is called chemotaxis. On reaching the tissue, they destroy cells and other structures that they per-ceive as nonself . This process is called phagocytosis. Of the white blood cells, neutrophilsand monocytes are most capable of phagocytosis. They do so by extending two arms of the cell mem-brane around the foreign or dead tissue. The two ex-tensions then fuse, engulfing the foreign tissue into the cytoplasm, forming what is called a phagosome. Lysosomes, vesicles containing digestive enzymes that are present in the cytoplasm of the white cell, fuse with the phagosome and kill and digest the en-gulfed debris.

Chemical Mediators

Alhough the process of inflammation is initiated by injury and death of cells, the signs and symptoms that accompany it are a result of locally liberated chemicals—the chemical mediators. These mediators are secreted in many ways. Some are secreted by white blood cells or by cells, such as mast cells, lo-cated in the connective tissue. Some of the mediators are formed by chemical reactions triggered locally by tissue injury. Some chemical mediators are hista-mines, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, bradykinin, tu- mor necrosis factor, and complement fractions.

SYMPTOMS ACCOMPANYINGINFLAMMATION

Whatever the cause, inflammation produces symp-toms that may last for only a few hours or for days. Remember a time when you had an injury or infec-tion. Fever, loss of appetite, lethargy, and sleepiness are some symptoms that you may have noticed. These responses are mainly a result of the chemical mediators. An increased number of white blood cells, an increased liver activity, and a decreased iron level in the blood (which results in anemia) are some un-seen responses that occur during the inflammatory process. Amino acids, the building blocks of protein, are used up to make new cells and form collagen for repair. This increase in energy usage, along with loss of appetite, is responsible for weight loss often seen with inflammation.

RESOLUTION OF INFLAMMATION

Inflammation can resolve in three ways: (1) it can slowly disappear, with the tissue appearing normal or close to normal (heal); (2) it can progress, with much fluid collecting in the area (exudative inflammation); or, (3) it can become chronic.

EXUDATIVE INFLAMMATION

Inflammation invariably results in different types of fluid collecting outside the cells in the injured area. This fluid is called an exudate. Exudates vary in composition of protein, fluid, and cell content. For example, after a small area of your skin is burned, a blister forms. This blister is filled with a clear exu-date, which indicates low protein content. This is known as serous exudate.

Inflammation sometimes results in a thick and sticky exudate that contains fibrous tissue. The fibers are actually a meshwork of proteins. When this type of inflammation resolves, increased adhesion and scar tissue often occurs in the area. This type of re-action is beneficial, however, as it causes the adjacent tissue to stick to each other and prevents spread of in-fection to surrounding areas. This exudate is known as fibrinous exudate.

The white fluid that collects in an inflamed area especially if it is infected, is pus, or purulent exu-date. The yellowish-white color of pus is actuallycaused by dead tissue, white blood cells, cellular de-bris, and protein. Purulent exudate may collect in dif-ferent ways. It may be collected within a capsule to form an abscess. If immunity is low, purulent exu-date may spread over a large surface of tissue.

Occasionally, the fluid that collects is blood-tinged. This is hemorrhagic exudate. In this case, the blood vessels are injured or the tissue is crushed. Inflam-mation may result in a membranous exudate, in which a membrane or sheet is formed on tissue sur-face. The membrane is a result of dead tissue caught up in the fibrous secretions.

CHRONIC INFLAMMATION

An inflammation is considered chronic when it per-sists over a long period. In some cases, it may persist for months and years. As a general rule, however, a chronic inflammation is one that lasts for longer than six weeks. Medically, inflammation is considered chronic if the area is infiltrated by many lymphocytes and macrophages, if growth of new capillaries oc-curs, and if there is an abundance of fibroblasts in the area. Usually inflammation becomes chronic when the initial injury or irritant persists. For example, people working with asbestos can have chronic in-flammation in the lungs resulting from inhaled as-bestos, a condition called asbestosis. Many bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites can also produce chronic inflammation. For example, tubercle bacillus, en-gulfed by macrophages, remains alive and produces chronic inflammatory changes in the lung. Chronic inflammation may present as fibrosis, ulcer, sinus, or fistula.

Fibrosis is a reaction caused by fibroblasts thatproduce collagen and fibrous tissue. Fibrosis results in the formation of scar tissue and adhesions.

In some cases, chronic inflammation may lead to ulcer formation. An ulcer is formed when an organor tissue surface is lost as a result of the death of cells and is replaced by inflammatory tissue. Usually, ulcers are found in the gut and the skin.

A sinus is another presentation of chronic inflam-mation. A sinus is a tract leading from a cavity to the surface. For example, sinuses may be associated with osteomyelitis, in which, as the bone cells die, they form an artificial tract leading from the bone to the surface of the skin through which the dead tissue ex-udes.

A fistula is a tract that is open at both ends and through which abnormal communication is estab-lished between two surfaces. For example, when cells die while receiving radiotherapy for treatment of cervical cancer, a fistula may develop between the blad-der and the vagina.

HEALING AND REPAIR

The outcome of inflammation depends on many is-sues. Other than the extent of the injury to the spe-cific tissue, repair and healing depend on the proper-ties of the cells in the tissue. The cells of the body can be divided into three groups, based on their capacity to regenerate—labile cells, stable cells, and perma-nent cells.

Cells with the capacity to regenerate throughout life quickly multiply and produce new cells to take the place of injured or dead tissue. These are known as labile cells.Examples are epidermal cells, geni- tourinary tract cells, cells lining the gut, hair follicle cells, and epithelial cells of ducts.

Another groups of cells, known as stable cells, have a low rate of division, but are able to regenerate if injured. Examples are liver cells, pancreatic cells, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells. To regenerate, these cells require the presence of a connective tissue framework. Also, a sufficient number of live cells must be present for regeneration to occur. For exam-ple, if extensive injury occurs in the liver, the connec-tive tissue framework is lost and the liver only heals by fibrosis, with liver failure as the outcome. How-ever, the liver can recover fully after minimal injury.

Cells of the nervous system, cardiac muscle, and skeletal muscle are referred to as permanent cells. These cells cannot divide, and the injured and dead cells are replaced by fibrous tissue and scar formation.

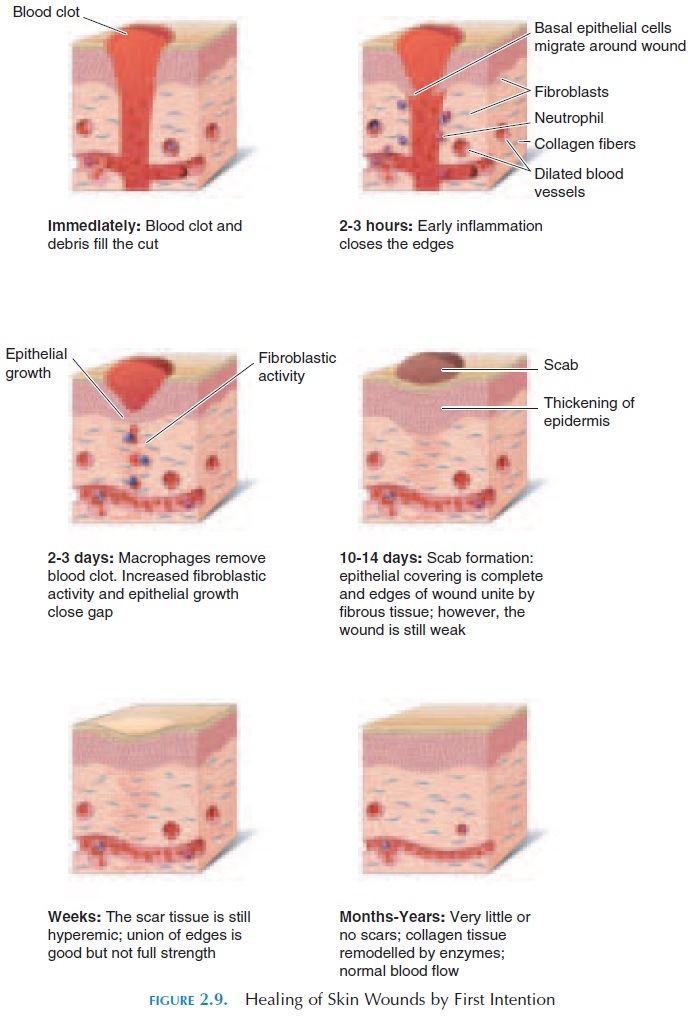

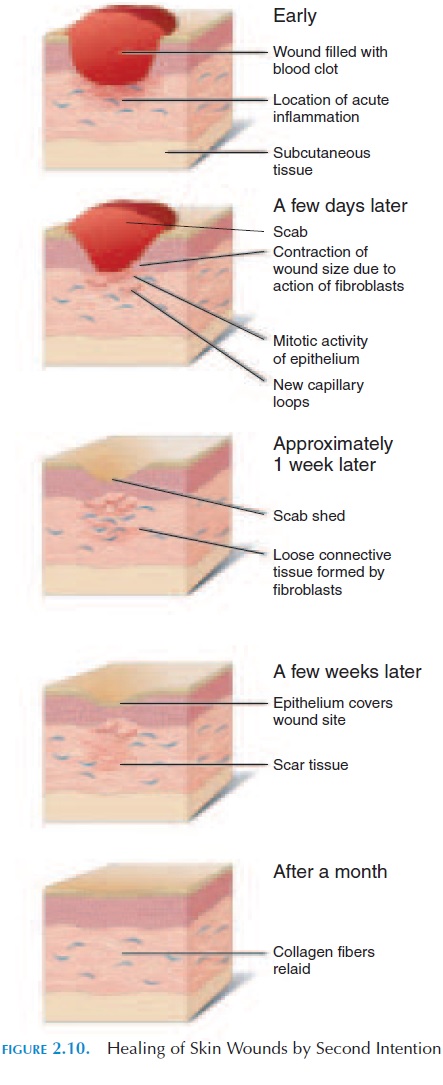

Study of the mechanisms involved in the healing of skin wounds gives insight into healing in general. Figures 2.9 and 2.10 show the mechanism involved in the healing of superficial (healing by first or primary intention) and deep (healing by second intention) skin wounds.

Related Topics