Chapter: Clinical Cases in Anesthesia : Neonatal Resuscitation

How is neonatal resuscitation managed in the delivery room?

How is neonatal resuscitation managed in the delivery room?

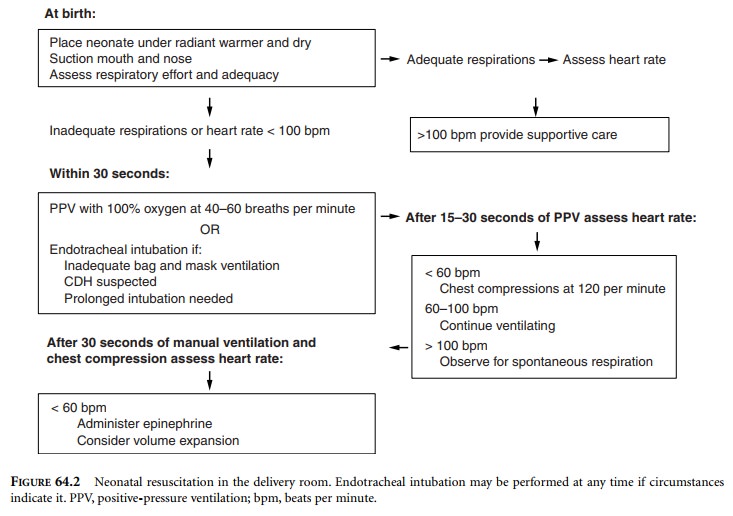

Within the first 20 seconds of birth, the

neonate should be placed under a radiant warmer and actively dried (Figure

64.2). The mouth and nose should be suctioned. Respiratory effort and adequacy

should be assessed within the first 30 seconds of birth. If there are adequate

sponta-neous respirations, the heart rate should then be assessed. If there is

no respiratory effort, inadequate respiratory effort (central cyanosis), or the

neonate is gasping, positive-pressure ventilation (PPV) with 100% oxygen should

be initiated at a rate of 40–60 breaths per minute with initial peak

inspiratory pressures of 30–40 cm H2O. Endotracheal intubation

should be performed if bag-and-mask ven-tilation is inadequate, a congenital

diaphragmatic hernia is suspected, or if there is a need for prolonged

intubation.

An endotracheal tube (3.0–3.5 mm ID) may also

be placed if a route for administration of resuscitative drugs is needed.

The heart rate should be checked after 15–30

seconds of PPV. If the heart rate is less than 60 beats per minute chest

compressions should be started at 120 compressions per minute. Chest

compressions can be accomplished in two ways:

·

Place

both thumbs on the lower sternum while the other fingers encircle the neonate

supporting the back.

·

Place

two fingers of one hand on the lower sternum while the other hand supports the

back.

The first method is preferred. Compressions

should be about one third of the depth of the chest. More impor-tantly,

compression depth should be sufficient to produce a palpable pulse. There

should be a 3:1 ratio of compres-sions to ventilations. Heart rate should be

reassessed every 30 seconds. Since cardiac depression is usually a result of

inadequate respirations, once oxygenation and ventilation is restored the heart

will in most cases resume normal function.

If after 30 seconds of manual ventilation and

chest com-pressions (90 seconds after birth) the heart rate remains below 60

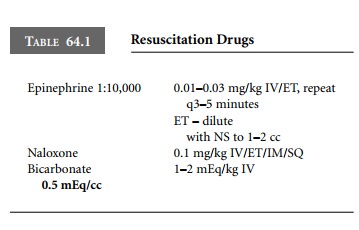

beats per minute, epinephrine should be administered. Epinephrine 1:10,000 at a

dose of 0.01–0.03 mg/kg can be given either intravenously or endotracheally.

The epinephrine may be diluted to 1–2 cc with normal saline for endotracheal

administration. This should be repeated every 3–5 minutes as indicated (Table

64.1).

Additional resuscitative measures may include

volume expansion with an isotonic crystalloid solution or colloids for the

hypovolemic infant. Hypovolemia should be suspected in the infant who is not

responding to the usual resuscitative measures or whose physical examination is

consistent with shock. The initial dose of fluid is 10 cc/kg as a bolus.

Additional fluid management should be based on clinical assessment.

Naloxone, a narcotic antagonist, is indicated

for the respiratory-depressed neonate born within 4 hours of the mother

receiving opioids. The recommended dose is 0.1 mg/kg and may be given by the

intravenous, endotra-cheal, intramuscular, or subcutaneous route. Naloxone is

not given to a neonate of a mother who is narcotic-addicted because it may

precipitate withdrawal in the neonate. Once naloxone is given, the neonate must

be observed for recur-rence of apnea because the duration of action of the

opioid may exceed the effect of the naloxone.

Sodium bicarbonate should not be used routinely

during resuscitation of the neonate. It is indicated only after prolonged

resuscitation and documented metabolic acidosis on arterial blood gas. Adequate

ventilation and circulation should be established prior to its administra-tion.

The recommended dose is 1–2 mEq/kg of a 0.5

mEq solution.

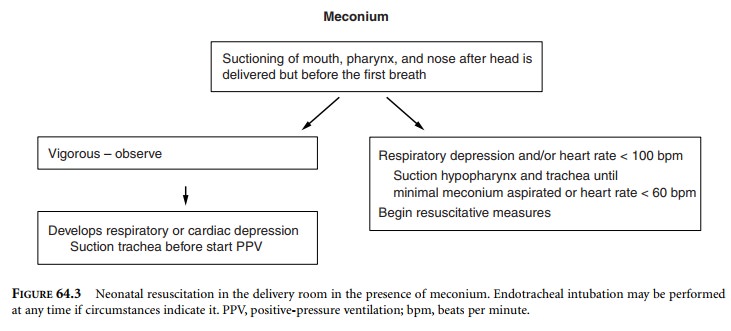

When meconium is present in the amniotic fluid,

specific steps should be taken to limit the risk of meconium aspiration (Figure

64.3). When the head of the neonate is delivered and prior to the neonate’s

first breath, suctioning of the mouth, pharynx, and nose should be done.

Despite this suctioning, there is a subset of neonates who will have meconium

in the trachea despite the absence of sponta-neous respirations. It is presumed

that this occurred in utero. If there is meconium-stained amniotic fluid and the

neonate is vigorous after delivery, there is no need to per-form tracheal

suctioning because it does not improve out-come. In fact, there may be

complications associated with tracheal suctioning such as laryngeal trauma.

However, if the neonate should develop respiratory or cardiac depres-sion

subsequently, suctioning of the trachea should pre-cede PPV. In the neonate who

has respiratory and/or cardiac depression (heart rate 60–100 beats per minute)

at birth, direct laryngoscopy should be performed to suction the hypopharynx

and to intubate the trachea for suctioning of any residual meconium that may be

present.

Repeated intubations and suctioning should be

performed until there is minimal meconium recovered or the heart rate is less

than 60 beats per minute. During this maneuver, an assistant should be

monitoring the heart rate continu-ously. Even if there is still meconium, once

the heart rate is less than 60 beats per minute, resuscitative measures should

be initiated immediately.

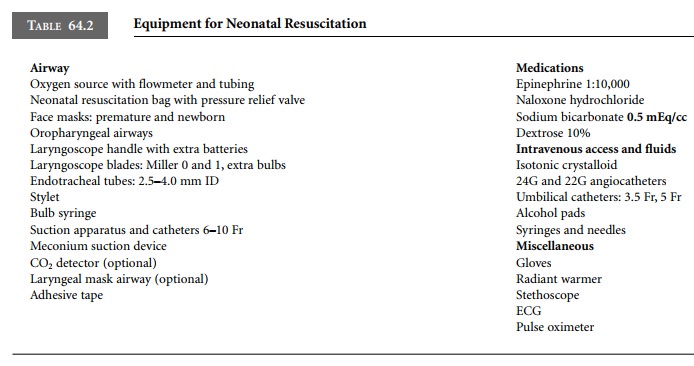

It is important that all the equipment and

pharmaco-logic agents necessary for resuscitation efforts are available and of

the appropriate size (Table 64.2).

Related Topics