Chapter: Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases: Bacterial Genetics

General Properties and Varieties of Plasmids - Bacterial Genetics

General Properties and Varieties of Plasmids

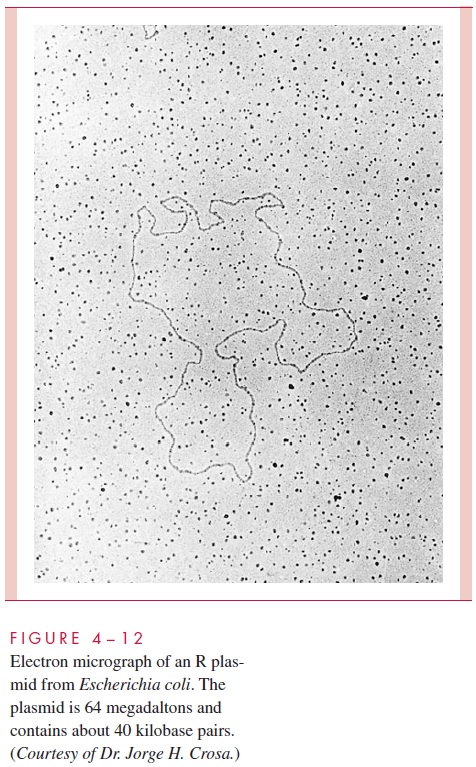

We have already encountered plasmids in our consideration of conjugation. To recap, plasmids are ubiquitous extrachromosomal elements composed of double-stranded DNA that typically is circular (Fig 4 – 12). (Linear plasmids occur in medically relevant strains of Borrelia.) A single organism can harbor several distinct plasmids. Like the chromosome,they have the property of governing their own replication by means of special sequences and regulatory proteins, including a genetic region called ori (origin of replication) at which specific proteins initiate replication. Any DNA molecule that is self-reproducing, in-cluding all plasmids as well as the bacterial chromosome, is said to be a replicon.

Plasmids vary greatly in size, in the mode of control of their replication, and in the number and kinds of genes they carry. Naturally occurring plasmids range from less than

The number of molecules of a given plasmid that is present in a cell, called the copy number, varies greatly among different plasmids, from only a few molecules per cell to dozens of molecules per cell. In general, small plasmids tend to be represented by more copies per cell.

Conjugal transfer is an important property of those plasmids that possess the com-plex of tra genes, but even nonconjugative plasmids can transfer to some extent to other cells as a result of mobilization by conjugative plasmids. Some plasmids, again including the F factor, can replicate either autonomously or as a segment of DNA inte-grated into the chromosome. These are sometimes termedepisomes. Certain prophages can exist as plasmids, but most plasmids are not viruses, because at no point of their life cycle do they exist as a free viral particle (virion). Most plasmids show little or no DNA homology with the chromosome and can, in this sense, be regarded as foreign to the cell.

Plasmids usually include a number of genes in addition to those required for their replication and transfer to other cells. The variety of cellular properties associated with plasmids is very great and includes fertility (the capacity for gene transfer by conjuga-tion), production of toxins, production of pili and other adhesins, resistance to antimicro-bics and other toxic chemicals, production of bacteriocins (toxic proteins that kill some other bacteria), production of siderophores for scavenging Fe3+ , and production of certain catabolic enzymes important in biodegradation of organic residues.

On the other hand, plasmids can add a small metabolic burden to the cell, and in many cases, a slightly reduced growth rate results. Thus, under conditions of laboratory cultivation where the properties coded by the plasmid are not required, there is a tendency forcuring of a strain to occur, because the progeny cells that have not acquired a plasmid (or have lost it) have a selective advantage during prolonged growth and subculture. Con-versely, where the property conferred by the plasmid is advantageous (eg, in the presence of the antimicrobic to which the plasmid determines resistance), selective pressure favors the plasmid-carrying strain.

Although plasmids are central to infectious disease and have been studied for decades, their origin remains uncertain. They could possibly be descendants of bacterial viruses that evolved a sophisticated means of self-transfer by conjugation and then lost their unneeded protein capsid. Alternatively, they may have evolved as separated parts of a bacterial chromosome that could provide both the means for genetic exchange and a way to amplify certain genes of special value in a particular environment (eg, coding for an adhesin) or to dispense with them where they are superfluous.

A great many bacterial plasmids are known. Some show similarity with each other in nucleotide sequence; thus, plasmids can be classified by their degree of apparent related-ness. Unrelated plasmids can coexist within a single cell, but closely related plasmids be-come segregated during cell division and eventually all but one are eliminated. For this reason, a group of closely related plasmids that exclude each other are referred to as an incompatibility group.

Related Topics