Chapter: Medical Physiology: The Body Fluid Compartments: Extracellular and Intracellular Fluids; Interstitial Fluid and Edema

Fluid Intake and Output Are Balanced During Steady-State Conditions

Fluid Intake and Output Are Balanced During Steady-State Conditions

The relative constancy of the body fluids is remarkable because there is con-tinuous exchange of fluid and solutes with the external environment as well as within the different compartments of the body. For example, there is a highly variable fluid intake that must be carefully matched by equal output from the body to prevent body fluid volumes from increasing or decreasing.

Daily Intake of Water

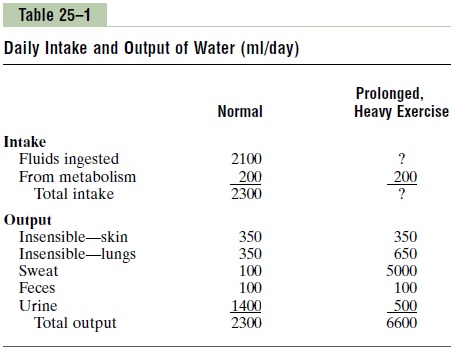

Water is added to the body by two major sources: (1) it is ingested in the form of liquids or water in the food, which together normally add about 2100 ml/day to the body fluids, and (2) it is synthesized in the body as a result of oxidation of carbohydrates, adding about 200 ml/day. This provides a total water intake of about 2300 ml/day (Table 25–1). Intake of water, however, is highly variable among different people and even within the same person on different days, depending on climate, habits, and level of physical activity.

Daily Loss of Body Water

Insensible Water Loss. Some of the water losses cannot be precisely regulated. Forexample, there is a continuous loss of water by evaporation from the respira-tory tract and diffusion through the skin, which together account for about 700 ml/day of water loss under normal conditions. This is termed insensiblewater loss because we are not consciously aware of it, even though it occurs con-tinually in all living humans.

The insensible water loss through the skin occurs independently of sweating and is present even in people who are born without sweat glands; the average water loss by diffusion through the skin is about 300 to 400 ml/day. This loss is minimized by the cholesterol-filled cornified layer of the skin, which provides a barrier against excessive loss by diffusion. When the cornified layer becomes denuded, as occurs with extensive burns, the rate of evaporation can increase as much as 10-fold, to 3 to 5 L/day. For this reason, burn victims must be given large amounts of fluid, usually intravenously, to balance fluid loss.

Insensible water loss through the respiratory tract averages about 300 to 400 ml/day. As air enters the respiratory tract, it becomes saturated with moisture, to a vapor pressure of about 47 mm Hg, before it is expelled. Because the vapor pressure of the inspired air is usually less than 47 mm Hg, water is continuously lost through the lungs with respiration. In cold weather, the atmospheric vapor pressure decreases to nearly 0, causing an even greater loss of water from the lungs as the temperature decreases. This explains the dry feeling in the respiratory passages in cold weather.

Fluid Loss in Sweat. The amount of water lost by sweat- ing is highly variable, depending on physical activity and environmental temperature. The volume of sweat normally is about 100 ml/day, but in very hot weather or during heavy exercise, water loss in sweat occa- sionally increases to 1 to 2 L/hour. This would rapidly deplete the body fluids if intake were not also increased by activating the thirst mechanism.

Water Loss in Feces. Only a small amount of water (100 ml/day) normally is lost in the feces. This can increase to several liters a day in people with severe diarrhea. For this reason, severe diarrhea can be life threatening if not corrected within a few days.

Water Loss by the Kidneys. The remaining water loss from the body occurs in the urine excreted by the kidneys. There are multiple mechanisms that control the rate of urine excretion. In fact, the most important means by which the body maintains a balance between water intake and output, as well as a balance between intake and output of most electrolytes in the body, is by con- trolling the rates at which the kidneys excrete these substances. For example, urine volume can be as low as 0.5 L/day in a dehydrated person or as high as 20 L/day in a person who has been drinking tremen- dous amounts of water.

This variability of intake is also true for most of the electrolytes of the body, such as sodium, chloride, and potassium. In some people, sodium intake may be as low as 20 mEq/day, whereas in others, sodium intake may be as high as 300 to 500 mEq/day. The kidneys are faced with the task of adjusting the excretion rate of water and electrolytes to match precisely the intake of these substances, as well as compensating for excessive losses of fluids and electrolytes that occur in certain disease states.

Related Topics