Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Sleep and Sleep-Wake Disorders

Dyssomnias: Differential Diagnosis

Differential

Diagnosis

Previously

called non-REM narcolepsy, this relatively rare disor-der is represented by

perhaps 5 to 10% of patients presenting to sleep disorders centers for

evaluation of hypersomnia. The diag-nosis must be made on the basis of

polysomnographic confirma-tion of hypersomnia; subjective complaints of

excessive sleepi-ness are not adequate. A family history of excessive

sleepiness may be present.

Although

usually seen as a persistent complaint, primary hypersomnia includes recurrent

forms, well defined with peri-ods of excessive sleepiness of at least 3 days’

duration occurring several times a year for at least 2 years. Among the

recurrent or intermittent hypersomnia disorders are Kleine–Levin syndrome,

usually seen in adolescent boys, and menstrual cycle-associ-ated hypersomnia

syndrome. In addition to hypersomnia (up to 18 hours per day), patients with

Kleine–Levin syndrome often demonstrate aggressive or inappropriate sexuality,

compulsive overeating and other bizarre behaviors. The rare nature of this

syndrome and its unusual behaviors may be mistaken for psycho-sis, malingering,

or a personality disorder.

Another syndrome, idiopathic recurring stupor, has been described and may be confused with hypersomnia. Patients ex-perience attacks of stupor or coma as infrequently as once or twice a year to as often as once a week. The duration of each episode varies from 2 hours to 4 days. Unlike patients with hy-persomnia, these patients are in a stuporous coma-like state and cannot be easily aroused or awakened. Furthermore, unlike the EEG of hypersomnia with its sleep spindles and K complexes, the EEG during stupor is characterized by diffuse activity at 13 to 18 Hz. Because the episode can be promptly but temporarily reversed by administration of flumazenil, a benzodiazepine re-ceptor antagonist, a search was made for an endogenous ligand for the benzodiazepine receptor in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid. The investigators discovered significantly increased levels of “endozepine 4” in blood and cerebrospinal fluid during periods of coma or stupor, suggesting that this syndrome is caused by this endogenous benzodiazepine-like compound. The syndrome occurs predominantly in men; mean age at onset is age 47 years (range, age 22–67 years). The cause is unknown.

Aside

from associated medical and psychiatric disorders, the frequency and importance

of hypersomnia and daytime sleepiness in otherwise healthy individuals have

been increas-ingly recognized. Sleepiness, for example, as a result of sleep

deprivation, disrupted sleep, or circadian dyssynchronization, probably plays a

major role in mistakes and accidents in sleepy drivers, interns and medical

staff, and industrial workers. Psychi-atrists have an obligation to recognize

and advise their patients about the dangers inherent in acute or chronic

sleepiness.

Treatment

Clinical management is controversial owing to the lack of con-trolled studies. As in narcolepsy, the stimulant compounds are the most widely used and most often successful of the treatment options available. However, some patients are intolerant of stim-ulants or report no significant therapeutic effects. For patients intolerant of, or insensitive to, stimulants, some success has been obtained with the use of stimulating antidepressants, both of the MAOI and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) classes. Methysergide, a serotonin receptor antagonist, may be effective in some treatment-resistant cases but must be used with caution in view of the possibility of pleural and retroperitoneal fibrosis with persistent, uninterrupted use. Careful documenta-tion should be maintained of interruption of drug use at regular intervals and of physical examinations that find the absence of obvious side effects of any sort.

Narcolepsy

Narcolepsy

is associated with a pentad of symptoms: 1) excessive daytime sleepiness,

characterized by irresistible “attacks” of sleep in inappropriate situations

such as driving a car, talking to a super-visor, or social events; 2)

cataplexy, which is sudden bilateral loss of muscle tone, usually lasting

seconds to minutes, generally pre-cipitated by strong emotions such as

laughter, anger, or surprise; 3) poor or disturbed nocturnal sleep; 4)

hypnagogic hallucinations, varied dreams at sleep onset; and 5) sleep

paralysis, a brief period of paralysis associated with the transitions into,

and out of, sleep.

The

disorder is lifelong. The first symptom is usually ex-cessive sleepiness,

typically developing during the late teens and early twenties. The full

syndrome of cataplexy and other symp-toms unfolds in several years

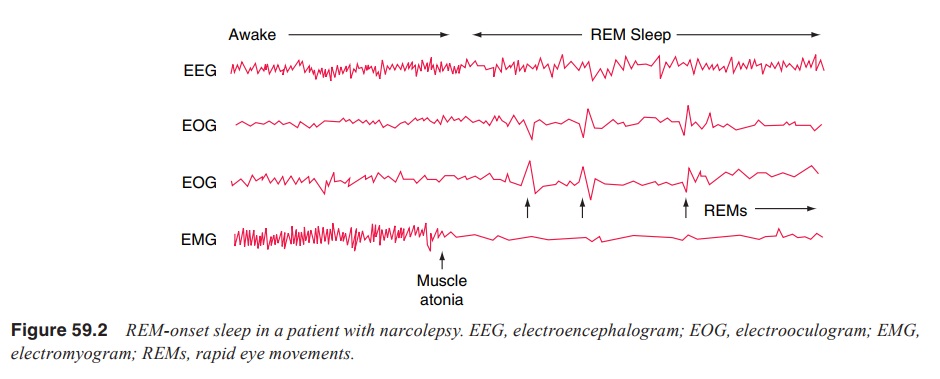

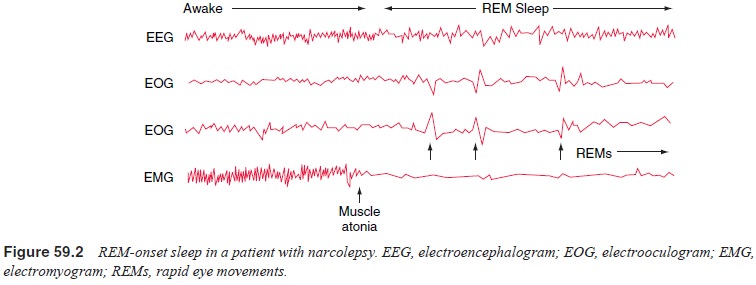

Narcolepsy

is now understood as an inherited, physiologi-cal disturbance of REM sleep

regulation. Narcoleptic patients often enter REM sleep right after sleep onset

(the “sleep-onset REM periods”), reflecting an abnormally short or even

nonex-istent first non-REM sleep period (Figure 59.2). Several of the core

symptoms of narcolepsy can be understood as abnormal physiological

representations of normal REM sleep. For exam-ple, cataplexy can be understood

as an abrupt presentation during wakefulness of the paralysis normally seen in

REM sleep. Cata-plexy is usually triggered by an emotional stimulus.

Sleep-onset REM periods may be subjectively appreciated as hypnagogic

hal-lucinations, which may be accompanied by sleep paralysis. Dis-sociated REM

sleep inhibition of the voluntary musculature may lead to complaints of

cataplexy and sleep paralysis.

In recent

years, a potential biochemical abnormality has been identified in both canine

and human narcolepsy. Nar-coleptic dogs appear to have a nonfunctional receptor

(OX2R) for orexin (hypocretin), a peptide neurotransmitter that has also been

associated with feeding and energy metabolism. “Knock-out” mice, which no

longer make this peptide, appear to have a narcoleptic-like syndrome. Levels of

orexin/hypocretin have been reported to be low in both autopsied brains and

spinal fluid in human narcoleptics

Diagnosis

Narcolepsy

is not a rare disease; the prevalence rate of 0.03 to 0.16% approximates that

of multiple sclerosis. Observers may mistake classic sleepiness in its mild

form as withdrawal, poor motivation, negativism and hostility. The hypnagogic

imagery and sleep paralysis symptoms, alone and in combination, may resemble

bizarre psychiatric illness. Like many medical disor-ders, narcolepsy presents

a wide range of severity, from mild to cases so severe that employment is

functionally impossible. Partial remissions and exacerbations occur. Sleep

paralysis and hypnagogic imagery may be seen without cataplexy; cataplexy may

present in isolation without other REM-associated phenom-ena. The presence of

REM sleep onset at night or during daytime naps, an important sleep laboratory

parameter, remains the most valid and reliable method available for diagnosing

narcolepsy. Because of the seriousness of the disorder and likelihood that

amphetamine or other stimulants will be used to treat the patient at some time,

it is important that the diagnosis of narcolepsy be objectively verified as

soon as possible. Furthermore, stimulant abusers have been known to feign

symptoms of narcolepsy to obtain prescriptions. Narcolepsy is associated with

significant social and financial impairment for affected individuals and their

families. For example, automobile accidents may result from ei-ther sleepiness

or cataplexy. Most states prohibit narcoleptic pa-tients from driving, at least

as long as they are symptomatic.

Treatment

The major

goals of treatment of narcolepsy include: 1) to improve quality of life, 2) to

reduce excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), and 3) to prevent cataplectic attacks.

The major

wake-promoting medications are: modafinil, amphetamine, dextraamphetamine and

methylphenidate. Mo-dafinil is preferred on grounds of efficacy, safety,

availability, and low risk of abuse and diversion. The pharmacological

treat-ment of cataplexy, sleep paralysis and hypnogogic hallucinations includes

administration of activating SSRIs such as fluoxetine and tricyclic

antidepressants such as protriptyline. Another new drug, sodium oxybate xyrem,

appears to be well tolerated and beneficial for the treatment of cataplexy,

daytime sleepiness and inadvertent sleep attacks (Littner et al., 2001; US Xyrem Multi-center Study Group, 2002).

Related Topics