Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Health Care Delivery and Nursing Practice

Demand for Quality Care - Influences on Health Care Delivery

DEMAND

FOR QUALITY CARE

The general public has

become increasingly interested in and knowledgeable about health care and

health promotion. This awareness has been stimulated by television, newspapers,

maga-zines, and other communications media and by political debate. The public

has become more health conscious and has in general begun to subscribe strongly

to the belief that health and quality health care constitute a basic right,

rather than a privilege for a chosen few.

In 1977, the National

League for Nursing (NLN) issued a statement on nurses’ responsibility to uphold

patients’ rights. The statement addressed patients’ rights to privacy,

confidentiality, informed participation, self-determination, and access to

health records. This statement also indicated ways in which respect for

patients’ rights and a commitment to safeguarding them could be incorporated

into nursing education programs and upheld and reinforced by those in nursing

service. Nurses can directly involve themselves in ensuring specific rights, or

they can make their in-fluence felt indirectly (NLN, 1977).

The ANA has worked

diligently to promote the delivery of quality health and nursing care. Efforts

by the ANA range from assessing the quality of health care provided to the

public in these changing times to lobbying legislators to pass bills related to

is-sues such as health insurance or length of hospital stay for new mothers.

Legislative changes have

promoted both delivery of quality health care and increased access by the

public to this care. The National Health Planning and Resources Act of 1974

empha-sized the need for planning and providing quality health care for all

Americans through coordinated health services, staffing, and facilities at the

national, state, and local levels. Medically under-served populations were the

target for the primary care services provided for by this act. By the passage

of bills supporting health insurance reform, barring discrimination against individuals

with preexisting conditions, and expanding the portability of health care

coverage, Congress has acknowledged the needs of con-sumers for adequate health

insurance in this time of longer life spans and chronic illnesses. Efforts in

some states to provide full health care coverage for citizens, particularly

children, represent measures by state governments to promote access to health

care. Legislative support of advanced practice nurses in individual practice is

a recognition of the contribution of nursing to the health of consumers,

particularly underserved populations.

Quality Improvement and Evidence-Based Practice

In the 1980s, hospitals

and other health care agencies implemented ongoing quality assurance (QA)

programs. These programs were required for reimbursement for services and for

accreditation by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare

Organizations (JCAHO). QA programs sought to establish accountability on the

part of the health professions to society for the quality, appropri-ateness,

and cost of health services provided.

The JCAHO developed a

generic model that required moni-toring and evaluation of quality and

appropriateness of care. The model was implemented in health care institutions

and agencies through organization-wide QA programs and reporting systems.Many

aspects of the programs were centralized in a QA depart-ment. In addition, each

patient care and patient services depart-ment was responsible for developing

its own plan for monitoring and evaluation. Objective and measurable indicators

were used to monitor, evaluate, and communicate the quality and

appro-priateness of care delivered.

In the early 1990s, it

was recognized that quality of care as de-fined by regulatory agencies

continued to be difficult to measure. QA criteria were identified as measures

to ensure minimal expec-tations only; they did not provide mechanisms for

identifying causes of problems or for determining systems or processes that

need improvement. Continuous quality improvement (CQI) was identified as a more

effective mechanism for improving the qual-ity of health care. In 1992, the

revised standards of the JCAHO mandated that health care organizations

implement a CQI pro-gram. Recent amendments to JCAHO standards have specified

that patients have the right to care that is considerate and pre-serves

dignity; that respects cultural, psychosocial, and spiritual values; and that

is age specific (Krozok & Scoggins, 2001). Qual-ity improvement efforts

have focused on ensuring that the care provided meets or exceeds JCAHO

standards.

Unlike QA, which focuses

on individual incidents or errors and minimal expectations, CQI focuses on the

processes used to provide care, with the aim of improving quality by assessing

and improving those interrelated processes that most affect patient care

outcomes and patient satisfaction. CQI involves analyzing, understanding, and

improving clinical, financial, or operational processes. Problems identified as

more than isolated events are an-alyzed, and all issues that may affect the

outcome are studied. The main focus is on the processes that affect quality.

As health care agencies

continue to implement CQI, nurses have many opportunities to be involved in

quality improvement. One such opportunity is through facilitation of

evidence-based practice. Evidence-based practice—identifying and evaluating

current literature and research and incorporating the findings into care

guidelines—has been designated as a means of ensuring quality care.

Evidence-based practice includes the use of outcome assessment and standardized

plans of care such as clinical guide-lines, clinical pathways, or algorithms.

Many of these measures are being implemented by nurses, particularly by nurse

managers and advanced practice nurses. Nurses directly involved in the

de-livery of care are engaged in analyzing current data and refining the

processes used in CQI. Their knowledge of the processes and conditions that

affect patient care is critical in designing changes to improve the quality of

the care provided.

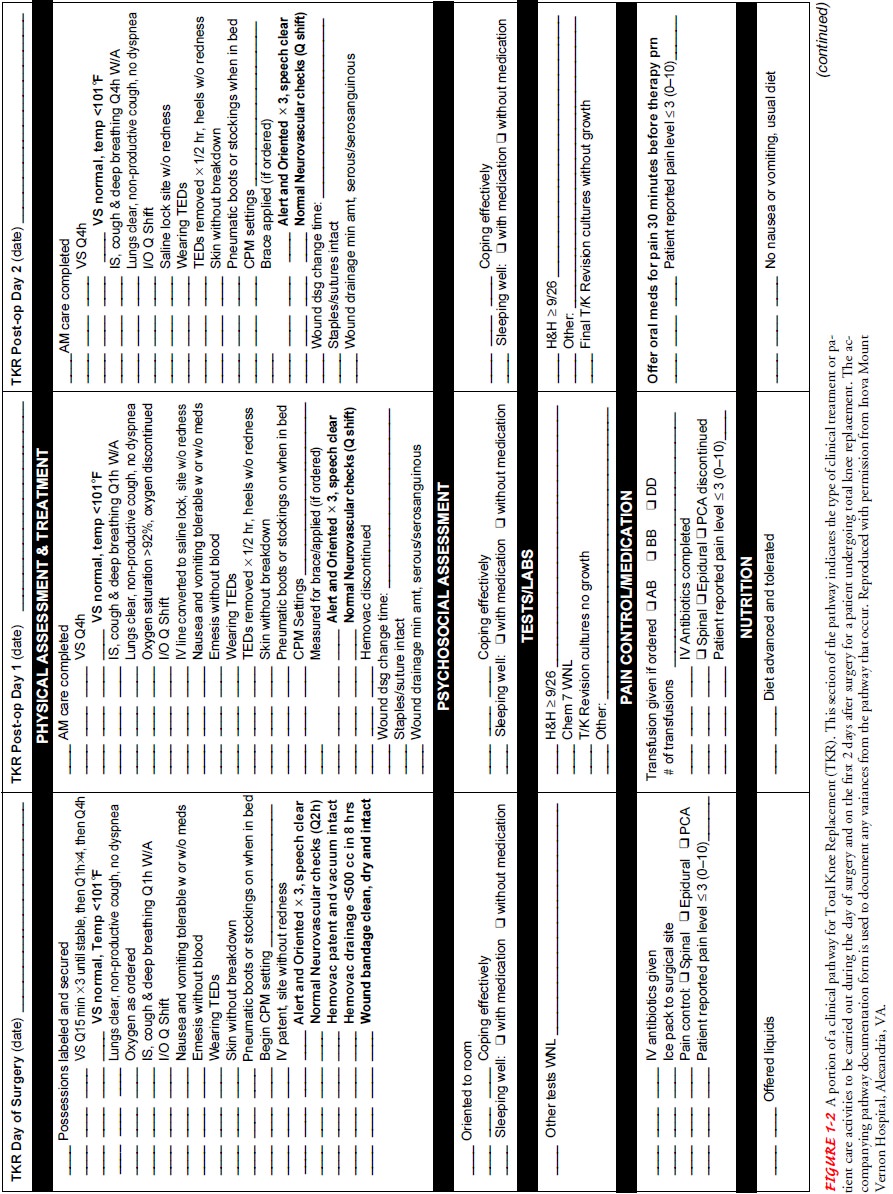

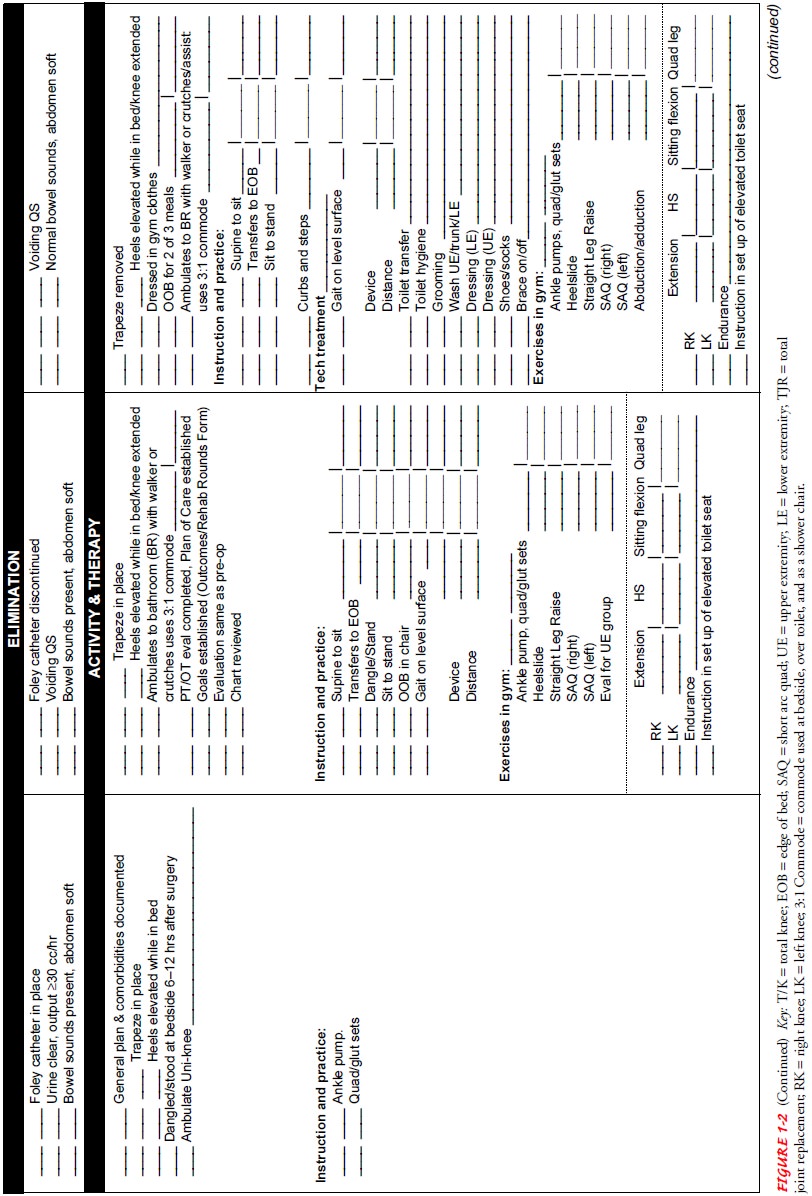

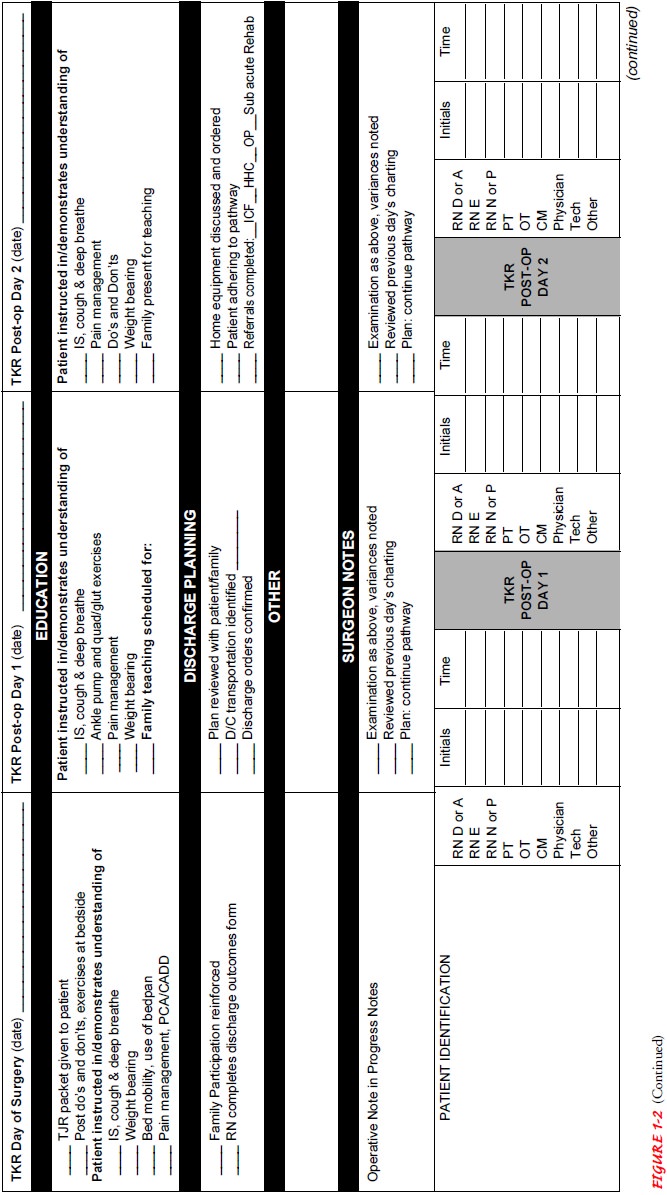

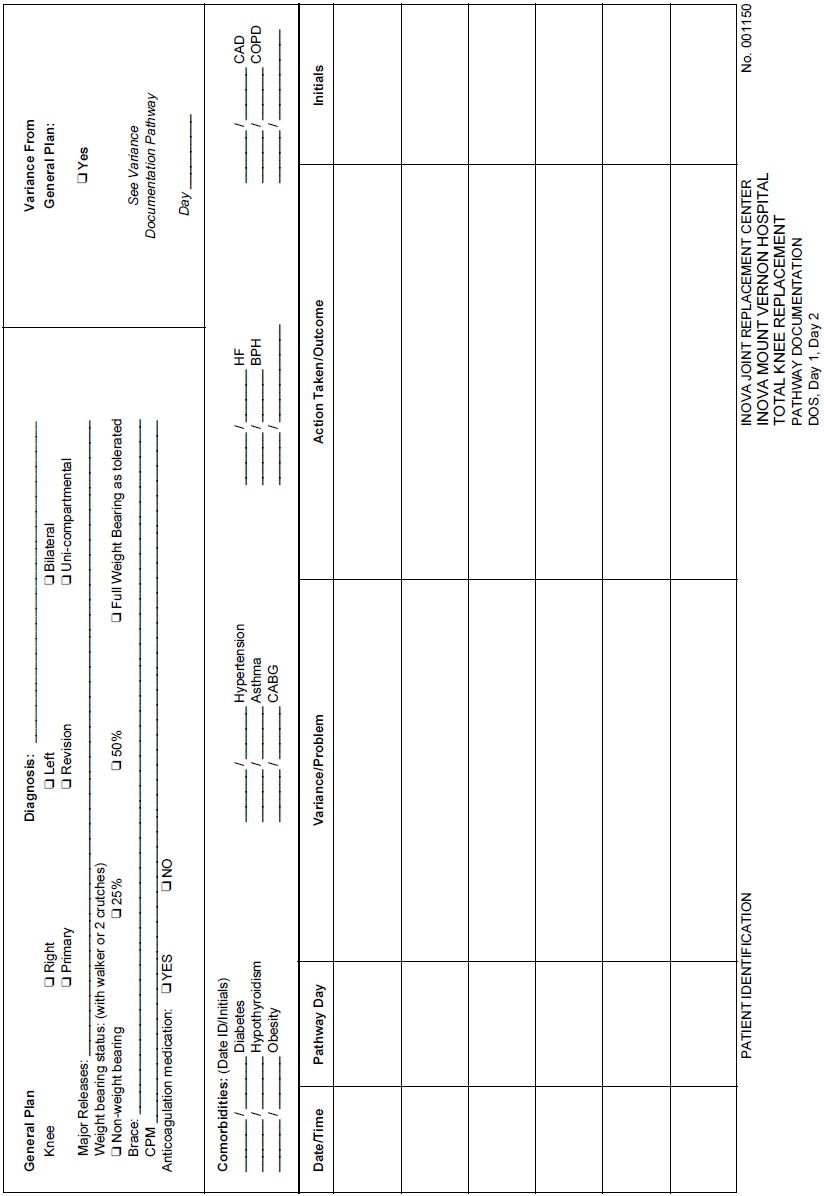

Clinical Pathways and Care Mapping

Many hospitals, managed

care facilities, and home health services nationwide use clinical pathways or

care mapping to coordinate care for a caseload of patients (Klenner, 2000).

Clinical pathways serve as an interdisciplinary care plan and as the tool for

tracking a patient’s progress toward achieving positive outcomes within

specified time frames. Clinical pathways have been developed for certain DRGs

(eg, open heart surgery, pneumonia with comor-bidity, fractured hip), for

high-risk patients (eg, those receiving chemotherapy), and for patients with

certain common health problems (eg, diabetes, chronic pain). Using current

literature and expertise, pathways identify best care. The pathway indicates

key events, such as diagnostic tests, treatments, activities, med-ications,

consultation, and education, that must occur within specified times for the

patient to achieve the desired and timely outcomes.

A case manager often

facilitates and coordinates interventions to ensure that the patient progresses

through the key events and achieves the desired outcomes. Nurses providing

direct care have an important role in the development and use of clinical

path-ways through their participation in researching the literature and then

developing, piloting, implementing, and revising clinical pathways. In

addition, nurses monitor outcome achievement and document and analyze

variances. Figure 1-2 presents an example of a clinical pathway. Other examples

of clinical pathways can be found in Appendix A.

Care mapping,

multidisciplinary action plans (MAPs), clini-cal guidelines, and algorithms are

other evidence-based practice tools that are used for interdisciplinary care

planning. These tools are used to move patients toward predetermined outcome

mark-ers using phases and stages of the disease or condition. Algorithms are

used more often in an acute situation to determine a particu-lar treatment

based on patient information or response. Care maps, clinical guidelines, and

MAPs (the most detailed of all tools) provide coordination of care and

education through hos-pitalization and after discharge (Cesta & Falter,

1999).

Because care mapping and

guidelines are used for conditions in which the patient’s progression often

defies prediction, specific time frames for achieving outcomes are excluded.

Patients with highly complex conditions or multiple underlying illnesses may

benefit more from care mapping or guidelines than from clinical pathways,

because the use of outcome markers (rather than spe-cific time frames) is more

realistic in such cases.

Through case management

and the use of clinical pathways or care mapping, patients and the care they

receive are continually assessed from preadmission to discharge—and in many

cases after discharge in the home care and community settings. These tools are

used in hospitals and alternative health care delivery systems to facilitate

the effective and efficient care of large groups of patients. The resultant

continuity of care, effective utilization of services, and cost containment are

expected to be major benefits for society and for the health care system.

Related Topics