Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Delirium and Dementia

Delirium

Delirium

Delirium (also known as acute confusional state,

toxic metabolic encephalopathy) is the behavioral response to widespread

distur-bances in cerebral metabolism. Like dementia, delirium is not a disease

but a syndrome with many possible causes that result in a similar constellation

of symptoms. DSM-IV-TR describes five categories of delirium based on etiology.

These include delirium due to a general medical condition, substance

intoxication, with-drawl delirium, delirium due to muttiple etiologies and

delirium not otherwise specified.

Epidemiology

The overall prevalence of delirium in the community

is low, but delirium is common in hospitalized patients. Lipowski (Saito, 1987)

reported studies of elderly patients and suggested that about 40% of them

admitted to general medical wards showed signs of delirium at some point during

the hospitalization. Because of the increasing numbers of elderly in this

country and the influence of life-extending technology, the population of

hospitalized elderly is rising; and so is the prevalence of delirium. The

intensive care unit, geriatric psychiatry ward, emergency department, alcohol

treatment units and oncology wards have particularly high rates of delirium.

Massie and colleagues (Lipowski, 1987) reported that 85% of terminally ill

patients studied had symptoms that met criteria for delirium, as did 100% of

postcardiotomy patients in a study by Theobald (Lipowski, 1989). Overall, it is

estimated that 10% of hospitalized patients are delirious at any particular

point in time.

Predisposing factors in the development of delirium in-clude old age, young age (children), previous brain damage, prior episodes of delirium, malnutrition, sensory impairment (espe-cially vision) and alcohol dependence. In general, the mortality and morbidity of any serious disease are doubled if delirium en-sues. The risk of dying after a delirious episode is greatest in the first two years after the illness, with a higher risk of death from heart disease and cancer in women and from pneumonia in men. Overall, the 3-month mortality rate for persons who have an epi-sode of delirium is about 28%, and the 1-year mortality rate for such patients may be as high as 50%.

Pathophysiology

ACh is the primary neurotransmitter believed to be

involved in delirium, and the primary neuroanatomical site involved is the

reticular formation. Thus, one of the frequent causes of delirium is the use of

drugs with high anticholingeric potential. As the principal site of regulation

of arousal and attention, the reticular formation and its neuroanatomical

connections play a major role in the symptoms of delirium. The major pathway

involved in de-lirium is the dorsal tegmental pathway projecting from the

mes-encephalic reticular formation to the tectum and the thalamus.

Clinical Features

According to DSM-IV-TR, the primary feature of

delirium is a diminished clarity of awareness of the environment (American

Psychiatric Association, 1994). Symptoms of delirium are char-acteristically

global, of acute onset, fluctuating and of relatively brief duration. In most

cases of delirium, an often overlooked pro-drome of altered sleep patterns,

unexplained fatigue, fluctuating mood, sleep phobia, restlessness, anxiety and

nightmares occurs. A review of nursing notes for the days before the recognized

onset of delirium often illustrates early warning signs of the condition.

Several investigators have divided the clinical

features of delirium into abnormalities of 1) arousal, 2) language and

cognition, 3) perception, 4) orientation, 5) mood, 6) sleep and wake-fulness,

and 7) neurological functioning (Kaplan et

al., 1994

The state of arousal in delirious patients may be

increased or decreased. Some patients exhibit marked restlessness, height-ened

startle, hypervigilance and increased alertness. This pattern is often seen in

states of withdrawal from depressive substances (e.g., alcohol) or intoxication

by stimulants (phencyclidine, am-phetamine, lysergic acid diethylamide).

Patients with increased arousal often have such concomitant autonomic signs as

pallor, sweating, tachycardia, mydriasis, hyperthermia, piloerection and

gastrointestinal distress. These patients often require seda-tion with

neuroleptics or benzodiazepines. Hypoactive arousal states such as those

occasionally seen in hepatic encephalopathy and hypercapnia are often initially

perceived as depressed or de-mented states. The clinical course of delirium in

any particular patient may include both increased and decreased arousal states.

Many such individuals display daytime sedation with nocturnal agitation and

behavioral problems (sundowning).

Perceptual abnormalities in delirium represent an inability to discriminate sensory stimuli and to integrate current percep-tions with past experiences. Consequently, patients tend to per-sonalize events, conversations and so forth that do not directly pertain to them, become obsessed with irrelevant stimuli and misinterpret objects in their environment. The misinterpreta-tions generally take the form of auditory and visual illusions. Patients with auditory illusions, for example, might hear the sound of leaves rustling and perceive it as someone whispering about them. Paranoia and sleep phobia may result. Typical visual illusions are that intravenous tubing is a snake or worm crawling into the skin, or that a respirator is a truck or farm vehicle about to collide with the patient. The former auditory illusion may lead to tactile hallucinations, but the most common hallucinations in delirium are visual and auditory.

Orientation is often abnormal in delirium.

Disorientation in particular seems to follow a fluctuating course, with

patients unable to answer questions about orientation in the morning, yet fully

oriented by the afternoon. Orientation to time, place, person and situation

should be evaluated in the delirious patient. Gener-ally, orientation to time

is the sphere most likely impaired, with orientation to person usually

preserved. Orientation to significant people (parents, children) should also be

tested. Disorientation to self is rare and indicates significant impairment.

The examiner should always reorient patients who do not perform well on any

portion of the orientation testing of the mental status examination, and serial

testing of orientation on subsequent days is important.

Language and Cognition

Patients with delirium frequently have abnormal

production and comprehension of speech. Nonsensical rambling and

incoherentspeech may occur. Other patients may be completely mute. Memory may

be impaired, especially primary and second-ary memory. Remote memory may be

preserved, although the patient may have difficulty distinguishing the present

from the distant past.

Mood

Patients with delirium are susceptible to rapid

fluctuations in mood. Unprovoked anger and rage reactions occasionally occur

and may lead to attacks on hospital staff. Fear is a common emo-tion and may

lead to increased vigilance and an unwillingness to sleep because of increased

vulnerability during somnolence. Apathy, such as that seen in hepatic

encephalopathy, depression, use of certain medications (e.g., sulfamethoxazole

[Bactrim]) and frontal lobe syndromes, is common as is euphoria secondary to

medications (e.g., corticosteroids, DDC, zidovudine) and drugs of abuse

(phencyclidine, inhalants).

Neurological Symptoms

Neurological symptoms often occur in delirium.

These include dysphagia as seen after a CVA, tremor, asterixis (hepatic

en-cephalopathy, hypoxia, uremia), poor coordination, gait apraxia, frontal

release signs (grasp, suck), choreiform movements seizures, Babinski’s sign and

dysarthria. Focal neurological signs occur less frequently.

Sleep–Wakefulness Disturbances

Sleeping patterns of delirious patients are usually

abnormal. During the day they can be hypersomnolent, often falling asleep in

midsentence, whereas at night they are combative and restless. Sleep is

generally fragmented, and vivid nightmares are com-mon. Some patients may

become hypervigilant and develop a sleep phobia because of concern that

something untoward may occur while they sleep.

Causes of Delirium

The cause of delirium may lie in intracranial

processes, extrac-ranial ones, or a combination of the two. The most common

etio-logical factors are as follows (Francis et al., 1990).

Infection Induced

Infection is a common cause of delirium in

hospitalized patients and typically, infected patients will display

abnormalities in he-matology and serology. Vital signs are noted except in

persons (elderly, chronic alcohol abusers, chemotherapy patients, those with

HIV spectrum disease) who may not be able to mount the typical response.

Bacteremic septicemia (especially that caused by gram-negative bacteria),

pneumonia, encephalitis and menin-gitis are common offenders. The elderly are

particularly suscep-tible to delirium secondary to urinary tract infections.

Metabolic and Endocrine Disturbances

Metabolic causes of delirium include hypoglycemia,

electro-lyte disturbances and vitamin deficiency states. The most com-mon

endocrine causes are hyperfunction and hypofunction of the thyroid, adrenal,

pancreas, pituitary and parathyroid. Meta-bolic causes may involve consequences

of diseases of particu-lar organs, such as hepatic encephalopathy resulting

from liver disease, uremic encephalopathy and postdialysis delirium re-sulting

from kidney dysfunction, and carbon dioxide macrosis and hypoxia resulting from

lung disease. The metabolic dis-turbance or endocrinopathy must be known to

induce changes in mental status and must be confirmed by laboratory

deter-minations or physical examination, and the temporal course of the

confusion should coincide with the disturbance (Francis et al., 1990). In some

individuals, particularly the elderly, brain

injured and demented, there may be a significant lag time be-tween

correction of metabolic parameters and improvement in mental state.

Low-perfusion States

Any condition that decreases effective cerebral

perfusion can cause delirium. Common offenders are hypovolemia, congestive

heart failure and other causes of decreased stroke volume such as arrhythmias

and anemia, which decreases oxygen binding. Main-tenance of fluid balance and

strict measuring of intake and output are essential in delirious states.

Intracranial Causes

Intracranial causes of delirium include head

trauma, especially involving loss of consciousness, postconcussive states and

hem-orrhage; brain infections; neoplasms; and such vascular abnor-malities as

CVAs, subarachnoid hemorrhage, transient ischemic attacks and hypertensive

encephalopathy.

Postoperative States

Postoperative causes of delirium may include

infection, atel-ectasis, postpump confusion from maintenance on a heart–lung

machine, lingering effects of anesthesia, thrombotic and embolic phenomena, and

adverse reactions to postoperative analgesia. General surgery in an elderly

patient has been reported to be fol-lowed by delirium in 10 to 14% of cases and

may reach 50% after surgery for hip fracture (Lipowski, 1989).

Sensory and Environmental Changes

Many clinicians underestimate the disorienting

potential of an unfamiliar environment. The elderly are especially prone to de-velop

environment-related confusion in the hospital. Individuals with preexisting

dementia, who may have learned to compensate for cognitive deficits at home,

often become delirious once hos-pitalized. In addition, the nature of the

intensive care unit often lends itself to periods of high sensory stimulation

(as during a “code”) or low sensory input, as occurs at night. Often, patients

use such external events as dispensing medication, mealtimes, presence of

housekeeping staff, and physicians’ rounds to mark the passage of time. These

parameters are often absent at night, leading to increased rates of confusion

during night-time hours. Often, manipulating the patient’s environment or

removing the patient from the intensive care unit can be therapeutic.

Substance Intoxication Delirium

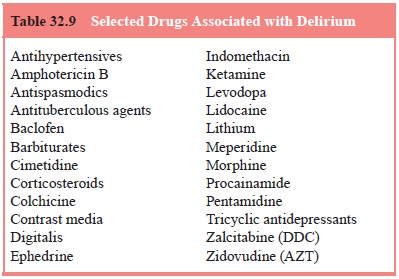

The list of medications that can produce the

delirious state is extensive (Table 32.9). The more common ones include such

antihypertensives as methyldopa and reserpine, histamine (H2)

receptor antagonists (cimetidine), corticosteroids, antide-pressants, narcotics

(especially opioid) and nonsteroidal anal-gesics, lithium carbonate, digitalis,

baclofen, anticonvulsants, antiarrhythmics, colchicine, bronchodilators,

benzodiazepines, sedative-hypnotics and anticholinergics. Of the narcotic

anal-gesics, meperidine can produce an agitated delirium with trem-ors,

seizures and myoclonus. These features are attributed to its active metabolite

normeperidine, which has potent stimulant and anticholingeric properties and

accumulates with repeated intravenous dosing. In general, adverse effects of

narcotics are more common in those who have never received such agents before

(the narcotically naive) or who have a history of a similar response to

narcotics.

Lithium-induced delirium occurs at blood levels

greater than 1.5 mEq/L and is associated with early features of lethargy,

stuttering and muscle fasciculations. The delirium may take as long as 2 weeks

to resolve even after lithium has been discon-tinued, and other neurological signs

such as stupor and seizures commonly occur. Maintenance of fluid and

electrolyte balance is essential in lithium-induced delirium. Facilitation of

excretion with such agents as aminophylline and acetazolamide helps, but

hemodialysis is often required.

Principles to remember in cases of drug-induced

delirium include the facts that 1) blood levels of possibly offending agents

are helpful and should be obtained, but many persons can be-come delirious at

therapeutic levels of the drug, 2) drug-induced delirium may be the result of

drug interactions and polypharmacy and not the result of a single agent, 3)

over-the-counter medica-tions and preparations (e.g., agents containing

caffeine or phenyl-propanolamine) should also be considered, and 4) delirium can

be caused by the combination of drugs of abuse and prescribed medications

(e.g., cocaine and dopaminergic antidepressants).

The list of drugs of abuse that can produce

delirium is ex-tensive. Some such agents have enjoyed a resurgence after years

of declining usage. These include lysergic acid diethylamide, psi-locybin

(hallucinogenic mushrooms), heroin and amphetamines. Other agents include

barbiturates, cannabis (especially depend-ent on setting, experience of the

user and whether it is laced with phencyclidine [“superweed”] or heroin),

jimsonweed (highly an-ticholingeric) and mescaline. In cases in which

intravenous use of drugs is suspected, HIV spectrum illness must be ruled out

as an etiological agent for delirium.

The physical examination of a patient with

suspected illicit drug-induced delirium may reveal sclerosed veins, “pop” scars

caused by subcutaneous injection of agents, pale and atrophic na-sal mucosa

resulting from intranasal use of cocaine, injected con-junctiva and pupillary

changes. Toxicological screens are helpful but may not be available on an

emergency basis.

Substance Withdrawal Delirium

Alcohol and certain sedating drugs can produce a

withdrawal delirium when their use is abruptly discontinued or signifi-cantly

reduced. Withdrawal delirium requires a history of use of a potentially

addicting agent for a sufficient amount of time to produce dependence. It is

associated with such typical physical findings as abnormal vital signs,

pupillary changes, tremor, dia-phoresis, nausea and vomiting, and diarrhea.

Patients generally

complain of abdominal and leg cramps, insomnia,

nightmares, chills, hallucinations (especially visual) and a general feeling of

“wanting to jump out of my skin”. Some varieties of drug with-drawal, although

uncomfortable, are not life threatening (e.g., opioid withdrawal). Others such

as alcohol withdrawal delirium are potentially fatal. Withdrawal delirium is

much more common in hospitalized patients than in patients living in the

community. The incidence of delirium tremens, for example, is found in 1% of

all alcoholics, but in 5% of hospitalized alcohol abusers. Im-provement of the

delirium occurs when the offending agent is reintroduced or a cross-sensitive

drug (e.g., a benzodiazepine for alcohol withdrawal) is employed. The causes of

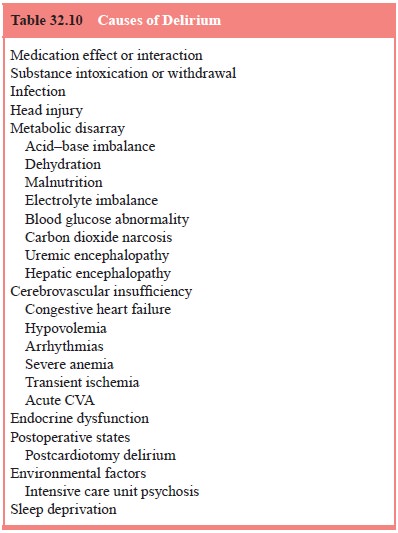

delirium are summarized in Table 32.10).

Diagnosis

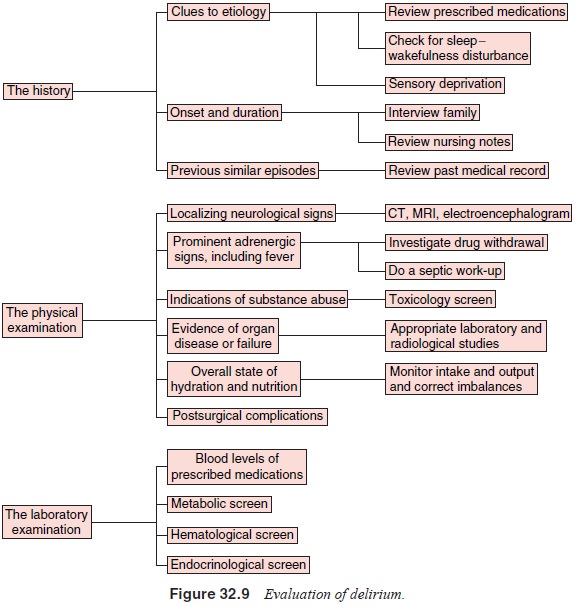

Appropriate workup of delirious patients includes a

complete physical status, mental status and neurological examination.

History taking from the patient, any available

family, pre-vious physicians, the old chart and the patient’s current nurse is

essential. Previous delirious states, etiologies identified in the past and

interventions that proved effective should be elucidated. The appropriate

evaluation of the delirious patient is reviewed in Figure 32.9

Differential Diagnosis

Delirium must be differentiated from dementia

because the two conditions may have different prognoses. In contrast to the

changes in dementia, those in delirium have an acute onset. The symptoms in

dementia tend to be relatively stable over time, whereas clinical features of

delirium display wide fluctuation with periods of relative lucidity. Clouding

of consciousness is an essential feature of delirium, but demented patients are

usu-ally alert. Attention and orientation are more commonly dis-turbed in

delirium, although the latter can become impaired in advanced dementia.

Perception abnormalities, alterations in the sleep–wakefulness cycle, and

abnormalities of speech are more common in delirium. Most important, a delirium

is more likely to be reversible than is a dementia.

Delirium and dementia can occur simultaneously; in

fact, the presence of dementia is a risk factor for delirium. Some stud-ies

suggest that about 30% of hospitalized patients with dementia have a

superimposed delirium.

Delirium must often be differentiated from

psychotic states related to such conditions as schizophrenia or mania and

factitious disorders with psychological symptoms or malinger-ing. Generally,

the psychotic features of schizophrenia are more constant and better organized

than are those in delirium, and pa-tients with schizophrenia seldom have the

clouding of conscious-ness seen in delirium. The “psychosis” of patients with

factitious disorder or malingering is inconsistent, and these persons do not

exhibit many of the associated features of delirium. Apathetic and lethargic

patients with delirium may occasionally resemble depressed individuals, but

tests such as EEG distinguish between the two. The EEG demonstrates diffuse

slowing in most delirious states, except for the low-amplitude, fast activity

EEG pattern seen in alcohol withdrawal. The EEG in a functional depression or

psychosis is normal.

Management

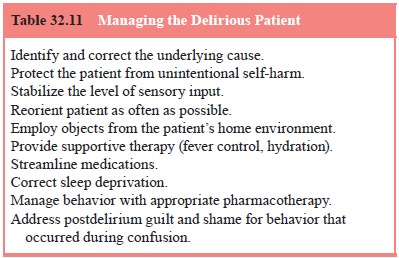

Once delirium has been diagnosed, the etiological

agent must be identified and treated. For the elderly, the first step generally

involves discontinuing or reducing the dosage of potentially of-fending

medications. Some delirious states can be reversed with medication, as in the

case of physostigmine administration for anticholinergic delirium. However,

most responses are not as immediate, and attention must be directed toward

protecting the patient from unintentional self-harm, managing agitated and

psy-chotic behavior, and manipulating the environment to minimize additional

impairment. Supportive therapy should include fluid and electrolyte maintenance

and provision of adequate nutrition. Reorienting the patient is essential and

is best accomplished in a well-lit room with a window, clock and visible wall

calendar. Familiar objects from home such as a stuffed animal, favorite

blanket, or photographs are helpful. Patients who respond incor-rectly to

questions of orientation should be provided with the correct answers. Because

these individuals often see many con-sultants, physicians should introduce

themselves and state their purpose for coming at every visit. Physicians must

take into ac-count that impairments of vision and hearing can produce

confu-sional states, and the provision of appropriate prosthetic devices may be

beneficial. Around-the-clock accompaniment by hospi-tal-provided “sitters” or

family members may be required (see Table 32.11).

these conservative interventions, the delirious pa-tient often requires pharmacological intervention. The liaison psy-chiatrist is the most appropriate person to recommend such treat-ment. The drug of choice for the agitated delirious patients has traditionally been haloperidol. It is particularly beneficial when given by the intravenous route and some authors have reported using dosages as high as 260 mg/day without adverse effect. Ex-trapyramidal symptoms may be less common with haloperidol administered intravenously as opposed to orally and intramuscu-larly. In general, doses in the range of 0.5 to 5 mg intravenously are used, with the frequency of administration depending on a variety of factors including the patient’s age. An electrocardio-gram should be obtained before administering haloperidol. If the QT interval is greater than 450, use of intravenous haloperidol can precipitate an abnormal cardiac rhythm known as Torsades de pointes. Lorazepam has also been proven effective in doses of 0.5 to 2 mg intravenously. Some authors have suggested that haloperidol and lorazepam act synergistically when given to the agitated delirious patient. If the delirium is secondary to drug or alcohol abuse, benzodiazepines or clonidine should be used

For patients who are mildly agitated or amenable to

taking medi-cations by mouth, oral haloperidol or lorazepam is appropriate.

Recent studies have advocated the use of newer atypical antipsy-chotics for

management of behavior and psychotic features in de-lirium. Such agents as

quetiapine, olanzapine, and risperdal and ziprasidone have been used

successfully to treat delirium. Newer agents may have lower incidences of

dystonias and dyskinesias, but still carry the risk of QT interval

prolongation, particularly in patients with electrolyte abnormalities.

Quetiapine and olanzap-ine are quite sedating, and occasionally a combination

of bedtime olanzapine and “as needed” haloperidol is utilized. Olanzapine may

raise blood glucose levels and precipitate weight gain, but is available as a

Zydis preparation, which is absorbed through the oral mucosa and can therefore

be given to patients who are unable to take medications by mouth. A parenteral

form of ziprasidone is also available. Whatever antipsychotic is chosen, the

patient should be carefully monitored for muscle rigidity, unexplained fever,

tremor and other warning signs of neuroleptic side effects.

Outcome of Delirium

After elimination of the cause of the delirium, the

symptoms gradually recede within 3 to 7 days. Some symptoms in certain

populations may take weeks to resolve. The age of the patient and the period of

time during which the patient was delirious affect the symptom resolution time.

In general, the patient has a spotty memory for events that occurred during

delirium. These remem- brances are reinforced by comments from the staff (“You’re

not as confused today”), or the presence of a sitter, or use of wrist

restraints. Patient should be reassured that they were not respon-sible for

their behavior while delirious, and that no one hates or resents them for the

behavior they may have exhibited. As men-tioned earlier, delirious patients

have an increased risk of mortal-ity in the year following their first episode.

Patients with underly-ing dementia show residual cognitive impairment after

resolution of delirium, and it has been suggested that a delirium may merge

into a dementia (Kaplan et al.,

1994).

Related Topics