Chapter: Psychology: Thinking

Decision Making: Reason-Based Choice

Reason-Based

Choice

How should we think about the

data we’ve reviewed? On the one side, our everyday experience suggests that we

often make good decisions—and so people are generally quite pleased with the

cell-phone model they selected, content with the car they bought, and happy

with the friends they spend time with. At the same time, we’ve considered

several obstacles to high-quality decision making: People can easily be tugged

one way or another by framing; they’re often inaccurate in predicting their own

likes and dislikes; and they seek out lots of choice and flexibility but end

up, as a result, less content with their own selections. How should we

reconcile all of these observations?

The answer may hinge on how we evaluate our decisions. If we’re

generally happy with our choices, this may in many cases reflect our

contentment with how we made thechoice rather

than what option we ended up with. In

fact, people seem to care a lot abouthaving a good decision-making process and

seem in many cases to insist on making a choice only if they can easily and

persuasively justify that choice.

Why should this be? Let’s start

with the fact that, for many of our decisions, our environment offers us a huge

number of options—different things we could eat, dif-ferent activities we could

engage in. If we wanted to find the best possible food, or the best possible

activity, we’d need to sift through all of these options and evaluate the

merits of each one. This would require an enormous amount of time—so we’d spend

too much of our lives making decisions, and we’d have no time left to enjoy the

fruits of those decisions. Perhaps, therefore, we shouldn’t aim our decisions

at the best possible outcome.

Instead, we can abbreviate the decision-making process if we simply aim at an

option that’s good enough for us,

even if it’s not the ideal. Said differently, it would take us too much time to

opti-mize (seeking the optimum

choice); doing so would involve exam-ining too many choices, and we’ve seen the

downside of that. Perhaps, therefore, we’re better advised to satisfice—by seeking a satisfactory

choice, even if it’s not the ideal, and ending our quest for a good option as

soon as we locate that satisfactory choice (Simon, 1983).

But how should we seek outcomes

that are “satisfactory”? One possibility is to make sure our decisions are

always justified by good reasons, so

that we could defend each decision if we ever needed to. A process like this

will often fail to bring us the best possible out-come, but at least it will

lead us to decisions that are reasonable— likely to be adequate to our needs.

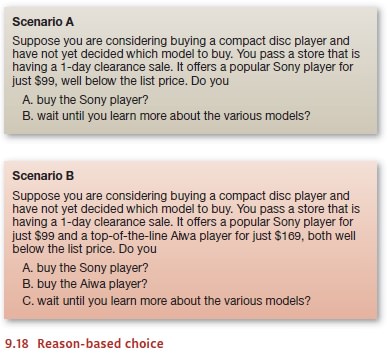

To see how this plays out,

consider a study in which half of the participants were asked to consider

Scenario A in Figure 9.18 (after Shafir, Simonson, & Tversky, 1993). In

this scenario, 66% of the participants said they would buy the Sony CD player;

only 34% said

they would instead wait until

they had learned about other models. Other participants, though, were presented

with Scenario B. In this situation, 27% chose the Aiwa, 27% chose the Sony, and

a much larger number—46%—chose to wait until they’d learned about other models.

In some ways, this pattern is

peculiar. The results from Scenario A tell us that the participants perceived

buying the Sony to be a better choice than continuing to shop; this is clear in

the fact that, by a margin of 2 to 1, people choose to buy. But in Scenario B,

participants show the reverse preference—choosing more shopping over buying the

Sony, again by almost 2 to 1. It seems, then, that participants are

flip-flopping; they pre-ferred the Sony to more shopping in one case and

indicated the reverse preference in the other.

This result makes sense, though,

when we consider that people usually seek a jus-tification

for their decisions and make a choice only when they find persuasive

rea-sons. When just the Sony is available, there are good arguments for buying

it. (It’s a popular model, available at a good price for just one day.) But

when both the Sony and the Aiwa are available, it’s harder to find compelling

arguments for buying one rather than the other. Both options are attractive

and, as a result, it’s hard to justify why you would choose one of these models

and reject the alternative. Thus, with no easy justification for a choice,

people end up buying neither. (Also see Redelmeier & Shafir, 1995, for a

parallel result involving medical doctors choosing treatments for their

patients.)

Related Topics