Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: The Cultural Context of Clinical Assessment

Cultural Competence

Cultural Competence

Recent years have seen the development of

professional stand-ards for training and quality assurance in cultural

compe-tence (Lopez, 1997; Sue, 1998). This term stands for a range of

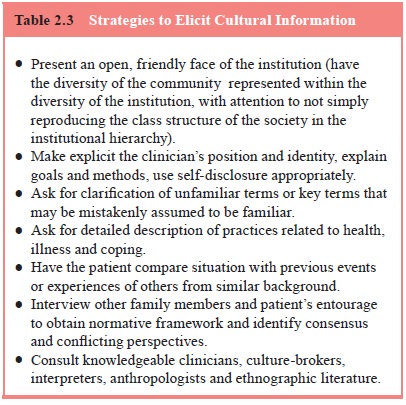

Table

2.3 Strategies to Elicit Cultural

Information

┬À

Present an open, friendly face of the institution (have the

diversity of the community represented within the diversity of the institution,

with attention to not simply reproducing the class structure of the society in

the institutional hierarchy).

┬À

Make explicit the clinicianÔÇÖs position and identity, explain

goals and methods, use self-disclosure appropriately.

┬À

Ask for clarification of unfamiliar terms or key terms that

may be mistakenly assumed to be familiar.

┬À

Ask for detailed description of practices related to health,

illness and coping.

┬À

Have the patient compare situation with previous events or

experiences of others from similar background.

┬À

Interview other family members and patientÔÇÖs entourage to

obtain normative framework and identify consensus and conflicting perspectives.

┬À

Consult knowledgeable clinicians, culture-brokers,

interpreters, anthropologists and ethnographic literature.

approaches aimed at improving the delivery of

appropriate serv-ices to a culturally diverse population. Cultural competence may

involve both culture-specific and generic strategies to address a range of

practical issues in intercultural work (Okpaku, 1998). This includes the

clinicianÔÇÖs ability to elicit cultural informa-tion during the clinical

encounter (Table 2.3), to understand how different cultural worlds of patients

and their families influence the course of the illness, and to develop a

treatment plan that empowers the patient by acknowledging cultural knowledge

and resources while allowing appropriate psychiatric intervention.

Specific cultural competence has to do with

knowledge and skills pertaining to a single cultural group, which may in-clude

history, language, etiquette, styles of child-rearing, emo-tional expression

and interpersonal interaction as well as cultural explanations of illness and

specific modalities of healing. Often, it is assumed that specific cultural

competence is assured when there is an ethnic match between clinician and

patient (e.g., aHispanic clinician treating a client from the same background).

However, ethnic matching without explicit training in models of culture and

intercultural interaction may not be sufficient to ensure that clinicians

become aware of their tacit cultural knowl-edge or biases and apply their

cultural skills in a clinically effec-tive manner.

Ethnic matching can occur at the level of the

individual, the technique, the institution, or any combination of these levels

(Weinfeld, 1999). At the level of the individual, it may be easier to establish

rapport when clinician and patient share a common background. However, there is

a risk that some issues may be left unexplored because they are taken for

granted, or are taboo and awkward to approach. There is also difficulty when

the pa-tientÔÇÖs expectations of a fellow community member are not met because

the clinician applies the rules and limits dictated by pro-fessional training.

This may include expectations of receiving special treatment, of being cured

quickly, of becoming friends, or intervening inappropriately on behalf of other

family or com-munity members.

In many cases, however, ethnic matching is only

crude or approximate. For example, the term Hispanic covers a broad ter-ritory with many cultural, educational

and social class differences that transcend language. Indeed, there is enormous

intracultural variation and no one person carries comprehensive knowledge of

his or her own cultural background, so there is always the need to explore

local meanings with patients.

In the course of professional training, clinicians

may dis-tance themselves from their own culture of origin and become reluctant

or unable to use (or understand the impact of) their tacit cultural knowledge

in their clinical work. Clinicians from ethnic minority backgrounds may resent

being pigeon-holed and expected to work predominately with a specific

ethnocultural group. Patients may have complex reactions to meeting a

clini-cian from the same background. These issues require attention and

sensitive exploration just as much as the feelings evoked by meeting someone

from a different background.

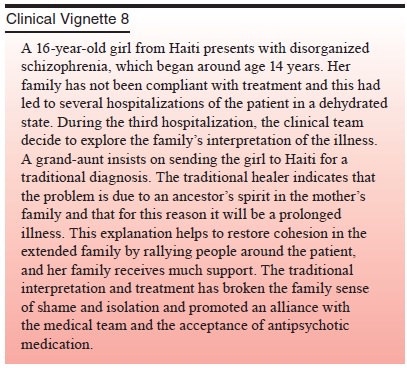

At the level of technique, the clinician familiar

with a spe-cific ethnocultural group learns to modify his or her approach to

take advantage of culturally supported coping strategies. For example, religious

practices, family and community supports, and appeals to specific cultural

values may all provide useful strategies for symptom management and improved

functioning. Traditional diagnostic and treatment methods may be used in

concert with conventional psychiatric treatments. The clinician may use his or

her own person differently in recognition of cul-tural notions of healing

relationships, adopting a more authorita-tive stance, making selective use

self-disclosure, or participating in symbolic social exchanges with patients

and their extended families to establish trust and credibility.

At the level of institutions, ethnic match is

represented in the organization of the clinical service, which should reflect

the composition of the communities it serves (Kareem and Littlewood, 1992).

This is not merely a matter of hiring prac-tices but also involves creating

structures that allow a measure of community feedback and control of the

service institution. When people feel a sense of ownership in an institution,

they will evince a higher level of trust and utilization. It is important,

therefore, for clinicians to understand how the institutional set-ting in which

they are working is seen by specific ethnocultural communities.

Increasingly, clinicians work in settings where

there is great cultural diversity that precludes reaching a high level of

specific competence for any one group. Changes in migration patterns and new

waves of immigrants and refugees lead to cor-responding changes in patient

populations. For all of these rea-sons, it is crucial to supplement specific

cultural competence with more generic competence that is based on a broad

theoreti-cal understanding of culture and ethnicity. Generic cultural

com-petence abstracts general principles from specific examples of cultural

differences. The core of generic competence resides in cliniciansÔÇÖ

understanding of their own cultural background and assumptions, some of which

are related to ethnicity and religion and many of which derive from

professional training and the con-text of practice. Appreciating the wide range

of cultural variation in gender roles, family structures, developmental

trajectories, explanations of health and illness, and responses to adversity

allows the clinician to ask appropriate questions about areas that would

otherwise be taken for granted. The culturally competent clinician has a keen

sense of what he or she does not know and a solid respect for difference. While

empathy and respectful in-terest allow the clinician gradually to come to know

anotherÔÇÖs world, the clinician must tolerate the ambiguity and uncertainty that

comes with not knowing. In the end, patients are the experts on their own

experiential worlds and cultural context must be reconstructed simultaneously

from the inside out (through the patientÔÇÖs experience) and from the outside in

(through an appre-ciation of the social matrix in which the patient is

embedded).

The wide range of specific and generic skills

needed for competent intercultural work means that most clinicians will find it

helpful to work in multidisciplinary teams that contain cultural diversity that

reflects the patient population. A variety of models for such teamwork have

been developed (Kareem and Littlewood, 1992; Kirmayer et al., 2003).

Related Topics