Chapter: Plant Biology : Spore bearing vascular plants

Clubmosses and horsetails

CLUBMOSSES AND HORSETAILS

Key Notes

Vegetative structure of Lycopsida

There are three groups of living clubmosses and quillworts, comprising about 1000 herbaceous species distributed world-wide. Clubmosses are terrestrial or epiphytic, and the quillworts aquatic. The clubmosses have branched stems with microphyll leaves, roots and, in Selaginella, rhizophores; the quillworts have a basal corm and long microphylls.

Reproduction in Lycopsida

Sporangia are produced in leaf axils, often in separate strobili with small leaves. Lycopodium and its relatives are homosporous but Selaginella andIsoetes heterosporous. Microspores may be very numerous in the sporangia but only four or a small number of megaspores are present in Selaginella, and up to one hundred in Isoetes.

Gametophyte of Lycopsida

Homosporous species have green or subterranean gametophytes, sometimes long-lived. Heterosporous species have reduced gametophytes contained within the sporangial wall. Female gametophytes may be dispersed after fertilization.

Fossil Lycopsida

Fossils go back to Devonian times, similar to current living members, particularly Selaginella. Heterosporous trees occur in Carboniferous rocks and they were important constituents of coal.

Vegetative structure of Equisetopsida

There are about 20 species of horsetails, world-wide in distribution. All are herbaceous but can reach 10 m. They have a jointed, ribbed stem with microphylls and whorls of branches and extensive rhizome and root systems. Silica is deposited giving them their roughness.

Reproduction in Equisetopsida

Strobili are produced at the ends of shoots, with sporangia at the branch tips. All are homosporous, the spores with elaters.

Gametophyte of Equisetopsida

These are green structures on the soil surface that may bear only antheridia or only archegonia, but archegonial ones produce antheridia as they age.

Fossil Equisetopsida

The earliest fossils come from the Devonian period, and some Carboniferous fossils resemble Equisetum. Others are trees up to 20 m tall, some heterosporous.

Vegetative structure of Lycopsida

The Lycopsida or lycopods today consist of about 1000 species of small non-woody plants known as clubmosses and quillworts, occurring throughout the world. They are mainly terrestrial, and one of the two groups of clubmosses, Selaginella species, can be abundant on the floor of tropical forests. Some are epiphytic while others occur in temperate mountains extending into the Arctic. The Isoetales (quillworts) are mainly aquatic plants. They have no particular human uses.

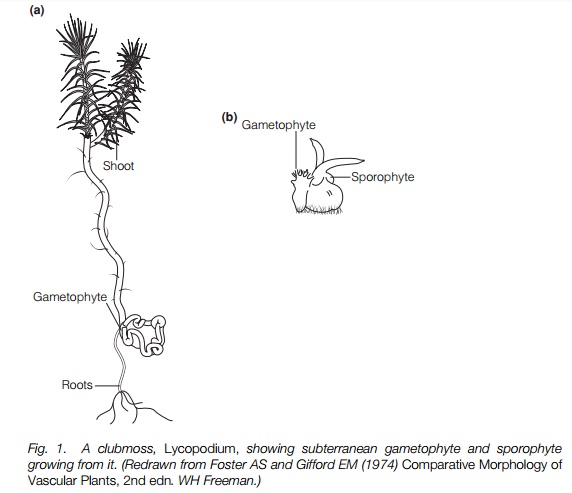

The living clubmosses (Fig. 1) have a shoot system that branches, often dichotomously, but sometimes with a main stem and side branches. These stems have a central vascular system with no pith and are covered with microphyll leaves. Microphylls (literally ‘small leaves’) are generally small, a few millimeters in length, and characterized by a single vascular strand through the middle. There is no gap in the conducting system of the stem where the leaf branches off. By contrast, the leaves of most other vascular plants, known as megaphylls, have a network of vascular strands and there is a gap in the stem vascular system where the leaf branches off.

Rhizomes may be present and roots branch from them. The roots branch dichotomously and regularly. In Selaginella, the roots branch from a curious structure intermediate between stems and roots, called a rhizophore.

These arise at angles in a stem and are unbranched, often aerial, but form roots when they touch the ground. They may represent a stage at which stems and roots were not fully differentiated.

The quillworts have only a basal corm, a short (about 1 cm) swollen stem or rootstock, which can show limited secondary growth and from which arises a rosette of remarkably long microphylls, often 10 cm or longer,and rhizoids, which, between them, completely conceal the corm. They closely resemble rosettes of aquatic flowering plants with which they often grow and do not resemble the clubmosses.

Reproduction in Lycopsida

One group of Lycopsida, including about 200 species of Lycopodium and its relatives, is homosporous; the other two groups, Selaginella (about 700 species) and Isoetes (about 70 species) are heterosporous . In all groups the sporangia are produced singly in the axils of leaves. In a few homosporous species there are fertile sections of the stem but in most there are separate strobili (singular strobilus). These consist of specialized scale-like microphylls with a different morphology from the vegetative leaves, often raised above the main stem. Nearly all Selaginella species have strobili and in Isoetes all leaves may bear sporangia.

The sporangium is normally 1–2 mm across, though larger in Isoetes. The sporangium consists of a wall, initially of several cell layers, though the inner layers break down as the spores mature. It dehisces along a line of thin-walled cells. In the heterosporous groups, strobili may contain a mixture of male sporangia and female sporangia, often with female at the base, or bear them in separate strobili. In the male sporangia, or microsporangia, there are numerous microspores, in Isoetes possibly as many as one million. In megasporangia of Selaginella there is usually one spore mother cell undergoing meiosis to produce four megaspores, though a few species may produce eight or more. In Isoetes more than 100 megaspores are produced in each sporangium.

Gametophyte of Lycopsida

In homosporous forms two types of gametophyte are known, both independent multicellular structures (Fig. 1). One type is cylindrical to 3 mm long and grows near the soil surface, becoming green and branched in the light, with sex organs, usually mixed, at the base of the branches. It lives for up to 1 year. The second type is subterranean or epiphytic and may live for 10 years before reaching 2 cm in length. It is oblong, disc-like or branched and antheridia are produced first in the center, while archegonia are produced later towards the edge. All areinfected with fungi that occupy a defined place and are essential for nutrition of the gametophyte and act as mycorrhizae do in angiosperms .

In heterosporous groups the gametophyte is much reduced and develops entirely within the spore wall, beginning development before leaving the sporangium. In microspores the first cell division leads to one vegetative cell known as the prothallus cell, and a second cell which divides to form the antheridium. The antheridium consists of a sterile jacket, but this and the prothallus cell disintegrate at maturity. In Selaginella biflagellate sperms, usually 128 or 256, all contained within the spore, are produced; in Isoetes just four multiflagellate sperms are produced. By this time the microspore has dispersed. The spore wall ruptures to release the sperms. In the megaspore, a gametophyte of many cells grows and the spore wall ruptures. Archegonia similar to those of bryophytes grow by the break. Dispersal of the female gametophyte occurs at different times in different species but in a few species it is retained until after fertilization and the embryo is growing.

Fossil Lycopsida

The clubmosses and quillworts are living remnants of a once much larger group with a rich fossil record including trees in late Devonian and Carboniferous times. Fossil lycopods are known from the early Devonian period onwards.

Devonian lycopods mostly resembled living homosporous clubmosses like Lycopodium, being herbaceous and most with dichotomous branching. Sporangia were sometimes stalked and borne on the leaves. By the Carboniferous period, herbaceous plants clearly seen to be heterosporous appear, and so closely resemble Selaginella that they are placed in the same genus.

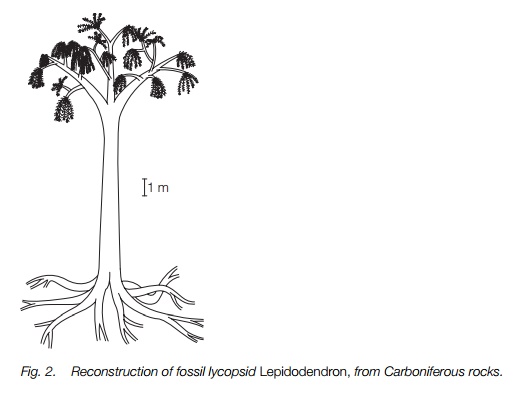

The best known fossil lycopods were trees, measuring ≥30 m. They are common fossils, beautifully preserved from the Carboniferous period in Britain and North America, and are important constituents of coal. They can be ascribed to the genus Lepidodendron which had a long unbranched trunk with dichotomous branching at its tip (Fig. 2). Strobili were produced at the branch ends and these were heterosporous. Microsporangia and megasporangia were similar to those of living heterosporous lycopods and the gametophytes were enclosed within the spore wall. In at least one species only one megaspore was produced within the sporangium and the whole structure was enclosed by a leaf-like outgrowth, to be dispersed together.

Vegetative structure of Equisetopsida

There is only one living genus and about 20 species in the Equisetopsida, known as horsetails, Equisetum. They are herbaceous perennial plants, mostly up to 1m in height, world-wide in distribution, but mostly in the northern temperate region where they are quite common. South and Central American species are taller, reaching 10 m, and in these the shoots are perennial. In the smaller northern plants, only the below-ground parts survive the winter.

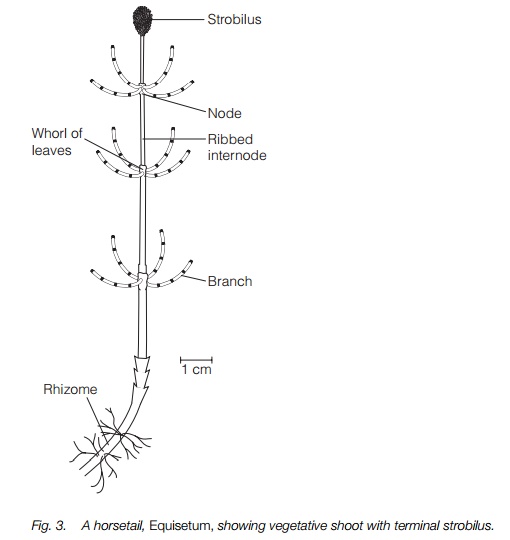

The living horsetails have a characteristic rough jointed stem (Fig. 3). This is ribbed, with scale-like microphyll leaves at the joints where they readily come apart. Most species have whorls of side branches from the main stem. They have an extensive rhizome system, the rhizomes being similar to the above-ground stem with nodes from which roots arise. This allows horsetails to colonize large patches, and their ability to regrow from a fragment of rhizome means they can be pernicious weeds. The stems have extensive deposits of silica along their length which gives them their rough texture, and their alternative name, ‘scouring rushes’, refers to the use of some as scourers. Growth abnormalities, such as no internodes or no side branches or dichotomous branching, are frequent in horsetails and this suggests that their growth regulation is poor.

Reproduction in Equisetopsida

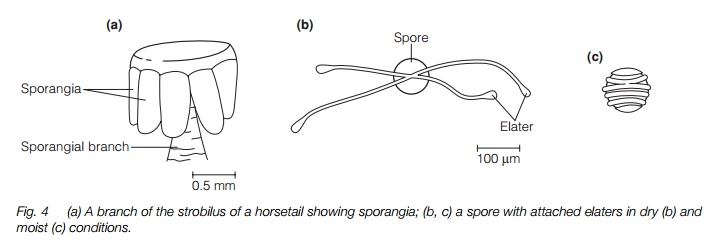

Sporangia are produced in strobili at the tip of either a vegetative shoot or a distinct, brownish fertile shoot (Fig. 3). The strobilus has short side branches each with an umbrella-shaped tip bearing 5–10 sporangia on the underside (Fig. 4), similar in structure to those of Lycopsida. The spores are unusual in that they contain chloroplasts and, at maturity, have four elaters (Fig. 4). These are short band-like structures with a spoon-shaped tip that coil around the spore at high humidity and uncoil as they dry, aiding dispersal. All horsetails are homosporous.

Gametophyte of Equisetopsida

Although the spores are apparently all identical in horsetails, gametophytes show a partial division of the sexes. They are green structures on a damp soil surface, with a colorless base and a much branched upper part, though they remain < 1 cm long. Gametophytes may produce antheridia or archegonia or both, any archegonial plants usually producing antheridia as they get older. The determination of sex seems to be at least partly environmental, and is flexible. The antheridia have a two-layered jacket and produce multi-flagellate sperm; the archegonia are similar to those of bryophytes .

Fossil Equisetopsida

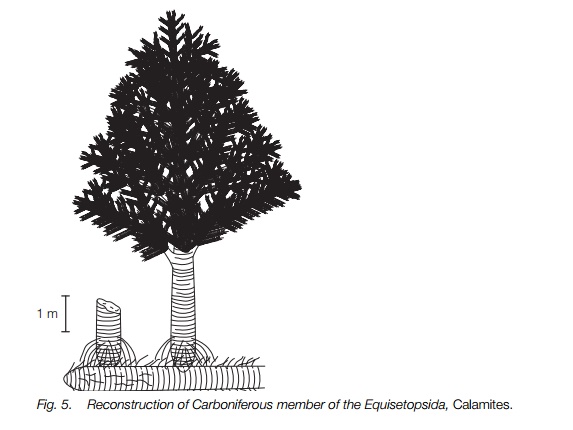

The fossil history of the group is rich, with the earliest fossils dating from the Devonian period where rhizomatous herbaceous plants with forked leaves and divided sporangial branches are known. In the Carboniferous other fossils appear, varied in the structure of their strobili, including climbing plants and a fossil closely resembling Equisetum itself, so this may be an ancient genus. The best known fossil Equisetopsids, also from the Carboniferous period, were large trees forming an important constituent of coal, Calamites and its relatives.

Calamites (Fig. 5) grew to approximately 20 m in height but had many featuresmsimilar to those of living horsetails. They had jointed ribbed stems, extensive branching and scale-like leaves, though these were often bigger than those of living horsetails. There was an underground rhizome system from which trunks grew and it is likely that these trees formed large patches. The stems had a large central pith but secondary thickening was extensive outside this. Strobili were borne on the side branches rather than at the tips but varied in structure, some having leaf-like bracts by each sporangium, and some clearly showing true heterospory with two different sizes of sporangium. Some species retained the megaspores in their sporangia on the parent plant to be dispersed as a unit.

Related Topics