Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Female Reproductive Disorders

Cancer of the Cervix

CANCER

OF THE CERVIX

Carcinoma

of the cervix is predominantly squamous cell cancer (10% are adenocarcinomas).

During the past 20 years, the inci-dence of invasive cervical cancer has

decreased from 14.2 cases per 100,000 women to 7.8 cases per 100,000 women. It

is less com-mon than it once was because of early detection of cell changes by

Pap smear. However, it is still the third most common female reproductive

cancer and affects about 13,000 women in the United States every year (American

Cancer Society, 2002). Cervical cancer occurs most commonly in women ages 30 to

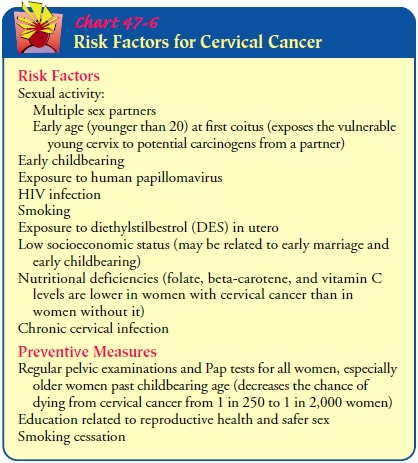

45, but it can occur as early as age 18. Risk factors include multiple sex

partners, early age at first coitus, short interval between menarche and first

coitus, sexual contact with men whose partners have had cervical cancer,

exposure to the HPV virus, and smoking (Chart 47-6).

Clinical Manifestations

There

are several different types of cervical cancer. Most cancers originate in

squamous cells, while the remainder are adenocarci-nomas or mixed adenosquamous

carcinomas. Adenocarcinomas begin in mucus-producing glands and are often due

to HPV in-fection. Most cervical cancers, if not detected and treated, spread

to regional pelvic lymph nodes, and local recurrence is not un-common. Early

cervical cancer rarely produces symptoms. If symptoms are present, they may go

unnoticed as a thin watery vaginal discharge often noticed after intercourse or

douching. When symptoms such as discharge, irregular bleeding, or bleed-ing

after sexual intercourse occur, the disease may be advanced. Advanced disease

should not occur if all women have access to gy-necologic care and avail

themselves of it. The nurse’s role in access and utilization is crucial and may

prevent the delay of detection of cervical cancer until the advanced stage.

In advanced cervical cancer, the vaginal discharge gradually increases and becomes watery and, finally, dark and foul-smelling from necrosis and infection of the tumor. The bleeding, which occurs at irregular intervals between periods (metrorrhagia) or after menopause, may be slight (just enough to spot the undergarments) and occurs usually after mild trauma or pressure (eg, intercourse, douching, or bearing down during defecation).

As the disease con-tinues, the bleeding may

persist and increase. Leg pain, dysuria, rec-tal bleeding, and edema of

extremities signal advanced disease.

As the

cancer advances, it may invade the tissues outside the cervix, including the

lymph glands anterior to the sacrum. In one third of patients with invasive

cervical cancer, the disease involves the fundus. The nerves in this region may

be affected, producing excruciating pain in the back and the legs that is

relieved only by large doses of opioid analgesic agents. If the disease progresses,

it often produces extreme emaciation and anemia, usually accom-panied by fever

due to secondary infection and abscesses in the ulcerating mass, and by fistula

formation. Because the survival rate for in situ cancer is 100% and the rate

for women with more advanced stages of cervical cancer decreases dramatically,

early de-tection is essential.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Diagnosis

may be made on the basis of abnormal Pap smear re-sults, followed by biopsy

results identifying severe dysplasia (cer-vical intraepithelial neoplasia type

III [CIN III], high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions [HGSIL] [also

referred to as HSIL], or carcinoma in situ; see below). HPV infections are

usu-ally implicated in these conditions. Biopsy results may indicate carcinoma

in situ. Carcinoma in situ is technically classified as se-vere dysplasia and

is defined as cancer that has extended through the full thickness of the

epithelium of the cervix, but not beyond. This is often referred to as

preinvasive cancer.

In its

very early stages, invasive cervical cancer is found mi-croscopically by Pap

smear. In later stages, pelvic examination may reveal a large, reddish growth

or a deep, ulcerating lesion. The patient may report spotting or bloody

discharge.

When

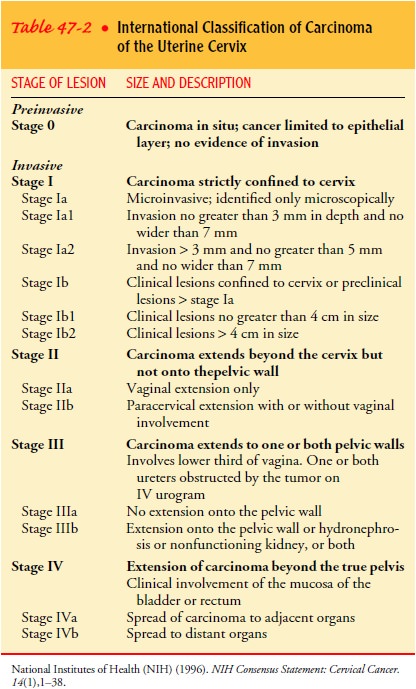

the patient has been diagnosed with invasive cervical cancer, clinical staging

estimates the extent of the disease so that treatment can be planned more

specifically and prognosis reasonably predicted. The International

Classification adopted by the International Federation of Gynecology and

Obstetrics and included in the NIH Consensus Conference on Cervical Cancer

(1996) (Table 47-2) is the most widely used staging system; the TNM (tumor,

nodes, and metastases) classification is also used in describing cancer stages.

In this system, T refers to the extent of the primary tumor, N to lymph node

involvement, and M to metastasis, or spread of the disease.

Signs

and symptoms are evaluated, and x-rays, laboratory tests, and special

examinations, such as punch biopsy and col-poscopy, are performed. Depending on

the stage of the cancer, other tests and procedures may be performed to

determine the ex-tent of disease and appropriate treatment. These tests include

dilation and curettage (D & C), computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI), intravenous urogra-phy, cystography, and barium x-ray

studies.

Medical Management

PRECURSOR OR PREINVASIVE LESIONS

When precursor lesions, such as low-grade squamous intra-epithelial lesion (LGSIL), which is also referred to as LSIL (CIN I and II or mild to moderate dysplasia), are found by colposcopy and biopsy, careful monitoring by frequent Pap smears or con-servative treatment is possible.

Conservative treatment may con-sist of monitoring, cryotherapy (freezing with nitrous

oxide), or laser therapy. A loop

electrocautery excision procedure (LEEP) may also be used to remove

abnormal cells. In this procedure, a thin wire loop with laser is used to cut

away a thin layer of cer-vical tissue. LEEP is an outpatient procedure usually

performed in a gynecologist’s office; it takes only a few minutes. Analgesia is

given before the procedure, and a local anesthetic agent is injected into the

area. This procedure allows the pathologist to examine the removed tissue

sample to determine if the borders of the tissue are disease-free. Another

procedure called a cone biopsy or conization

(removing a cone-shaped portion of the cervix) is per-formed when biopsy

findings demonstrate CIN III or HGSIL, equivalent to severe dysplasia and

carcinoma in situ.

If

preinvasive cervical cancer (carcinoma in situ) occurs when a woman has

completed childbearing, a hysterectomy is usually recommended. If a woman has

not completed childbearing and invasion is less than 1 mm, a cone biopsy may be

sufficient. Fre-quent re-examinations are necessary to monitor for recurrence.

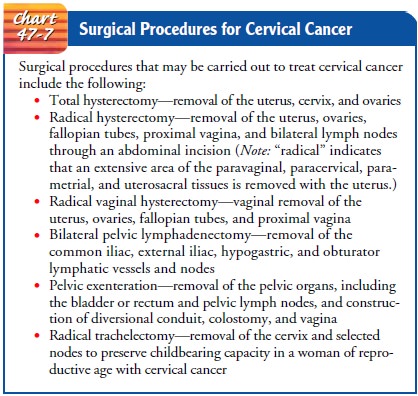

A

newly developed procedure called a radical trachelectomy is an alternative to

hysterectomy in women with cervical cancer who are young and want to have

children (Dargent, Martin, Sacchetoni & Mathevet, 2000). In this procedure

the cervix is gripped with retractors and pulled into the vagina until it is

visi-ble. The affected tissue is excised while the rest of the cervix and

uterus remain intact. A drawstring suture is placed to close the cervix.

Patients

who have precursor or premalignant lesions need re-assurance that they do not

have invasive cancer. However, the im-portance of close follow-up is emphasized

because the condition, if untreated for a long time, may progress to cancer.

Patients with cervical cancer in situ also need to know that this is usually a

slow-growing and nonaggressive type of cancer that is not expected to recur

after appropriate treatment.

INVASIVE CANCER

Treatment

of invasive cervical cancer depends on the stage of the lesion, the patient’s

age and general health, and the judgment and experience of the physician.

Surgery and radiation treatment (intra-cavitary and external) are most often

used. When tumor invasion is less than 3 mm, a hysterectomy is often

sufficient. Invasion ex-ceeding 3 mm usually requires a radical hysterectomy

with pelvic node dissection and aortic node assessment. Stage 1B1 tumors are

treated with radical hysterectomy and radiation. Stage 1B2 tu-mors are treated

individually because no single correct course has been determined, and many

variable options may be seen clini-cally (Chart 47-7). Frequent follow-up after

surgery by a gyne-cologic oncologist is imperative because the risk of

recurrence is 35% after treatment for invasive cervical cancer. Recurrence

usu-ally occurs within the first 2 years. Recurrences are often in the upper

quarter of the vagina, and ureteral obstruction may be a sign. Weight loss, leg

edema, and pelvic pain may be signs of lym-phatic obstruction and metastasis.

Radiation, which is often part of treatment to reduce recurrent disease, may be delivered by an external beam or by brachyther-apy (method by which the radiation source is placed near thetumor) or both. The field to be irradiated and dose of radiation are determined by stage, volume of tumor, and lymph node in-volvement. Treatment can be administered daily for 4 to 6 weeks followed by one or two treatments of intracavitary radiation. Inter-stitial therapy may be used when vaginal placement has become impossible due to tumor or stricture.

Platinum-based

agents are being used to treat advanced cervi-cal cancer. They are often used

in combination with radiation therapy, surgery, or both. Studies are ongoing to

find the best ap-proach to treat advanced cervical cancer. Vaginal stenosis is

a fre-quent side effect of radiation. Sexual activity with lubrication is

preventive, as is use of a vaginal dilator to avoid severe permanent vaginal

stenosis.

Some

patients with recurrences of cervical cancer are consid-ered for pelvic exenteration, in which a large

portion of the pelvic contents is removed. Unilateral leg edema, sciatica, and

ureteral obstruction indicate likely disease progression. Patients with these

symptoms have advanced disease and are not consid-ered candidates for this

major surgical procedure. Surgery is often complex because it is performed

close to the bowel, blad-der, ureters, and great vessels. Complications can be

considerable and include pulmonary emboli, pulmonary edema, myocardial

infarction, cerebrovascular accident, hemorrhage, sepsis, small bowel

obstruction, fistula formation, urinary obstruction of ileal conduit, bladder

dysfunction, and pyelonephritis, most often in the first 18 months. Vein

constriction must be avoided post-operatively. Patients with varicose veins or

a history of throm-boembolic disease may be treated prophylactically with

heparin. Pneumatic compression stockings are prescribed to reduce the risk for deep

vein thrombosis. Nursing care of these patients is complex and requires

coordination and care by experienced health care professionals. This is a

complex, extensive surgical procedure that is reserved for those with a high

likelihood of cure.

Related Topics