Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Childhood Disorders: The Autism Spectrum Disorders

Autism Spectrum Disorders: Assessment and Differential Diagnosis

Assessment and Differential

Diagnosis

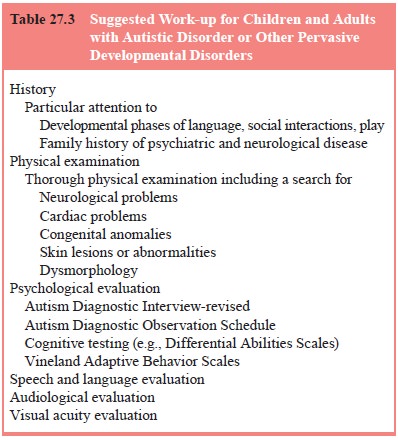

The diagnosis of ASD first involves completing a

comprehen-sive psychiatric examination (Table 27.3). The clinician should

obtain a full developmental history, including all information regarding

pregnancy and delivery. While questioning about neonatal development,

particular attention should be paid tosocial, communicative and motor

milestones. The clinician needs to understand fully the child’s adaptive

skills, includ-ing which tasks can be undertaken independently, including

grooming skills, feeding skills and the ability to self-initiate. There should

be a sense of the child’s vocabulary, receptive and expressive language skills,

articulation and pragmatic commu-nication. A full medical history should be

obtained, and should include queries regarding any hearing or vision problems, any

history of seizures and information regarding the use of any medications.

Because these children dislike novelty, the first

visit to the clinician’s office is sometimes an anxiety-provoking undertak-ing.

It is not unusual (and is in fact helpful diagnostically) to al-low a child

with ASD to extensively explore the clinician’s office, looking under desks or

opening drawers, in an attempt to become familiar with the surroundings. Some

children will appear shy and self-absorbed. It is ideal if the clinician can

arrange an op-portunity to see the child in another environment in addition to

the office. Observation of the child interacting with the parents and siblings

is helpful in understanding modes of interaction and social skills. If the

child is having difficulty, it is usually prefer-able, especially on the first

visit, to allow the parents to inter-vene. This will allow the clinician to see

how (effectively) the family responds to this distress, and how the child

responds to the efforts of caregivers to soothe the child. During observation,

the clinician needs to assess social interaction, communication, unusual

behaviors and all other information in the context of de-velopmental level.

A full physical examination should be undertaken

includ-ing observations for dysmorphic features and unusual dermato-logic

lesions. The clinician must maintain a high suspicion for seizures in this

population, both when taking the history and dur-ing the examination. A full

neurological examination should be made with an emphasis on motor impairments.

A Wood’s light examination for hypopigmented lesions consistent with tuberous

sclerosis should be made

There are no diagnostic laboratory tests for ASD.

If the child has not had routine tests (blood count, liver function tests,

thyroid, lead level, etc.), these should be completed, as with any child.

Patients with mental retardation or dysmorphology should have chromosomal

analysis performed. Fragile X testing and fluorescent in situ hybridization

(FISH) studies for possible in-terstitial duplication of 15q11–13 should be

suggested after con-sultation with the family. There should be a low threshold

for ordering an electroencephalogram (EEG), and one should always be ordered in

the context of unusual movements, regressive be-havior, regressive loss of

previously acquired sleep, or in the face of unusually poor sleep. Structural

brain imaging (i.e., MRI) should take place only if the physical examination or

history sug-gests that a treatable lesion is present. Carried out routinely,

these scans have a very low clinical yield, are quite expensive, and in this

population often require anesthesia, a seemingly unneces-sary risk.

Consultative services should be utilized as needed with pediatric neurologists

and geneticists. Difficulties with motor de-velopment will often mean a

referral to an occupational and/or physical therapist. Children with Rett’s

syndrome will often re-quire referral to neurologists and developmental

pediatricians.

All children with autism require a careful language

assess-ment that may include hearing testing and assessment of expres-sive and

receptive, verbal and nonverbal language. Speech and language therapists

trained to work with this population are an essential part of the assessment

team.

Children with ASD should have a neuropsychological

as-sessment at the time of initial assessment and at periodic intervals

thereafter. The initial evaluation helps establish the diagnosis and a baseline

level of functioning. Additionally, it can be utilized to make the appropriate

adjustments in the child’s educational plan. The later evaluations serve to

chart progress, evaluate the success of (pharmacological, behavioral and

academic) interven-tions, and to assess for possible regression in particular

areas.

While there are many rating scales and structured

interviews to assist in making the diagnosis of ASD, the current gold standard

in diagnostic assessment is the autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic

(ADOS-G) (Lord et al., 2000). This is

often given with the autism diagnostic inventory-revised (ADI-R) (Lord et al., 1994), which is a comprehensive,

clinician-administered interview of the patient’s primary caregiver and covers

most developmental and behavioral aspects of autism. The ADI/ADOS combination

is now established as a reliable and valid method for making the diagnosis of

ASD.

Related Topics