Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Female Physiologic Processes

Assessment of Female Physiologic Processes: Physical Assessment

PHYSICAL

ASSESSMENT

Periodic

examinations and routine cancer screening are important for all women. An

annual breast and pelvic examination is im-portant for all women age 18 or

older and for those who are sex-ually active, regardless of age. The patient

deserves understanding and support because of the emotional and physical

considerations associated with gynecologic examinations. Women may be sensi-tive

or embarrassed by the usual questions asked by a gynecologist or women’s health

care provider. Because gynecologic conditions are of a personal and private

nature to most women, such infor-mation is shared only with those directly

involved in patient care (as is true with all patient information).

Throughout

the examination, the nurse explains the proce-dures to be performed. This not

only encourages the woman to relax but also provides an opportunity for her to

ask questions and minimizes the negative feelings that many women associate

with gynecologic examinations.

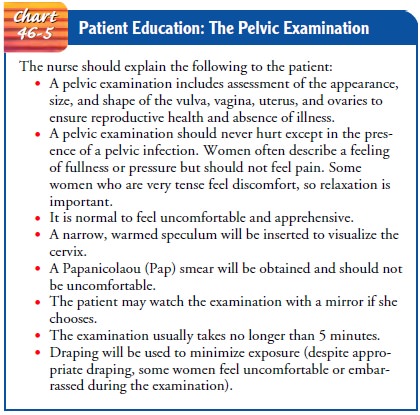

The

first pelvic examination is often anxiety-producing for women; the nurse can

alleviate many of these feelings with expla-nations and teaching (Chart 46-5).

Before the examination begins, the patient is asked to empty her bladder and to

provide a urine specimen if urine tests are part of the total assessment.

Voiding en-sures patient comfort and eases the examination because a full

bladder can make palpation of pelvic organs uncomfortable for the patient and

difficult for the examiner.

Positioning

Although

several positions may be used for the pelvic examination, the supine lithotomy

position is used most commonly, although the upright lithotomy position (in

which the woman assumes a semisitting posture) may also be used. This position

offers several advantages:

· It is more comfortable

for some women.

· It allows better eye

contact between patient and examiner.

· It may provide an easier

means for the examiner to carry out the bimanual examination.

· It enables the woman to use a mirror to see her anatomy (if she chooses) to visualize any conditions that require treatment or to learn about using certain types of contraceptive methods.

In the

supine lithotomy position, the patient lies on the table with her feet on foot

rests or stirrups. She is encouraged to relax so that her buttocks are

positioned at the edge of the examination table, and she is asked to relax and

spread her thighs as widely apart as possible.

If the patient is too ill, disabled, or neurologically impaired to lie safely on the examination table or cannot maintain the supine litho-tomy position, the Sims’ position may be used. In Sims’ position, the patient lies on her left side with her right leg bent at a 90-degree angle. The right labia may be retracted to gain adequate access to the vagina. Other positions for pelvic examination for disabled women make the examination easier for the woman and the clini-cian. The presence of a disability does not justify skipping any parts of the physical assessment, including the pelvic examination.

The

following equipment is obtained and readily available: a good light source; a

vaginal speculum; clean examination gloves; lubricant, spatula, cytobrush,

glass slides, fixative solution or spray; and diagnostic testing supplies for

screening for occult rectal blood if the woman is older than 40. Latex-free

gloves should be avail-able if the patient or clinician is allergic to latex.

This allergy is be-coming more prevalent in nurses and other health care

providers and patients and is potentially life-threatening. Patients should be

questioned about previous reactions to latex.

Inspection

After

the patient is prepared, the examiner inspects the labia ma-jora and minora,

noting the epidermal tissue of the labia majora; the skin fades to the pink

mucous membrane of the vaginal in-troitus. Lesions of any type (eg, venereal

warts, pigmented lesions [melanoma]) are evaluated. In the nulliparous woman,

the labia minora come together at the opening of the vagina. In women who have

delivered children vaginally, the labia minora may gape and vaginal tissue may

protrude.

Trauma

to the anterior vaginal wall during childbirth may have resulted in

incompetency of the musculature, and a bulge caused by the bladder protruding

into the submucosa of the an-terior vaginal wall (cystocele) may be seen. Childbirth trauma may also have affected

the posterior vaginal wall, producing a bulge caused by rectal cavity

protrusion (rectocele). The cervix

may descend under pressure through the vaginal canal and be seen at the

introitus (uterine prolapse). To

identify such protrusions, the examiner asks the patient to “bear down.”

The

introitus should be free of superficial mucosal lesions. The labia minora may

be separated by the fingers of the gloved hand and the lower part of the vagina

palpated. In virgins, a hymen of

variable thickness may be felt circumferentially within 1 or 2 cm of the

vaginal opening. The hymenal ring usually permits the insertion of one finger.

Rarely, the hymen totally occludes the vaginal entrance (imperforate hymen).

In

women who are not virgins, a rim of scar tissue represent-ing the remnants of

the hymenal ring may be felt circumferen-tially around the vagina near its

opening. The greater vestibular glands (Bartholin’s glands) lie between the

labia minora and the remnants of the hymenal ring. An abscess of the

Bartholin’s gland can cause discomfort and requires incision and drainage.

Speculum Examination

The

bivalved speculum, either metal or plastic, is available in many sizes. Metal

specula are soaked, scrubbed, and sterilized be-tween patients. Some clinicians

and some patients prefer plastic specula, which permit one-time use. The

speculum should be warmed with a heating pad or warm water to make insertion

more comfortable for the patient. The speculum is not lubricated because

commercial lubricants interfere with cervical cytology (Papanicolaou [Pap]

smear) findings.

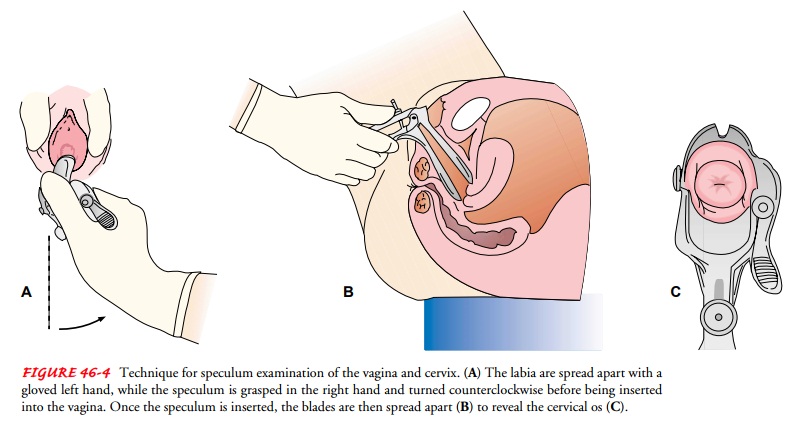

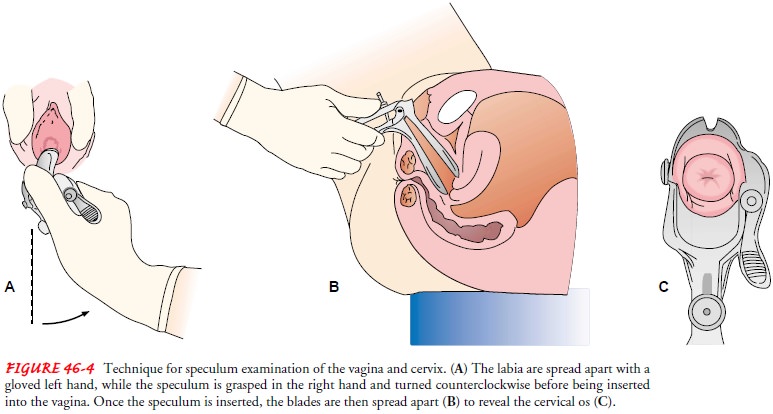

The metal

speculum has two set-screws. The one along the handle, holding the two valves

of the speculum together, is kept tightened. The screw that holds the thumb

rest in place is loos-ened. The speculum is grasped in the dominant hand, with

the thumb against the back of the thumb rest to keep the tips of the valves

closed. The speculum is rotated slightly counterclockwise, and the vaginal

orifice is held open by the thumb and the fore-finger of the gloved nondominant

hand by some examiners. Other examiners find that straight insertion of a

speculum with downward pressure on the vagina is more comfortable for the

pa-tient. The speculum is gently inserted into the posterior portion of the

introitus and slowly advanced to the top of the vagina; this should not be

painful or uncomfortable for the woman. The tip of the speculum may then be

elevated and the speculum rotated to a transverse position. The speculum is

then slowly opened and the set-screw of the thumb rest is tightened to hold the

speculum open (Fig. 46-4).

CERVIX

The

cervix is inspected. In nulliparous women, the cervix usually is 2 to 3 cm wide

and smooth. Women who have borne children may have a laceration, usually

transverse, giving the cervical os a “fishmouth” appearance. Epithelium from

the endocervical canal may have grown onto the surface of the cervix, appearing

as beefy-red surface epithelium circumferentially around the os. Occasion-ally,

the cervix of a woman whose mother took DES has a hooded appearance (a peaked

aspect superiorly or a ridge of tissue sur-rounding it); this is evaluated by

colposcopy when identified.

ABNORMAL GROWTH

Malignant changes may not be obviously

differentiated from the rest of the cervical mucosa. Small, benign cysts may

appear on the cervical surface. These are usually bluish or white and are

called nabothian cysts. A polyp of

endocervical mucosa may protrude through the os and usually is dark red. Polyps

can cause irregular bleeding; they are rarely malignant and usually are removed

eas-ily in an office or clinic setting. A carcinoma may appear as a

cauliflower-like growth that bleeds easily when touched. Bluish col-oration of

the cervix is a sign of early pregnancy (Chadwick’s sign).

PAP SMEAR

During the pelvic examination, a Pap smear is

obtained by rotat-ing a small spatula at the os, followed by a cervical brush

rotated in the os. The tissue obtained is spread on a glass slide and sprayed

or fixed immediately, or inserted into a liquid. A small broom-like device can

also be used to obtain specimens for the Pap smear.

A specimen of any purulent material appearing at the cervical os is obtained for culture. A sterile applicator is used to obtain the specimen, which is immediately placed in an appropriate medium for transfer to a laboratory. In patients at high risk for infection, routine cultures for gonococcal and chlamydial organisms are rec-ommended because of the high incidence of both diseases and the high risk for pelvic infection, fallopian tube damage, and sub-sequent infertility.

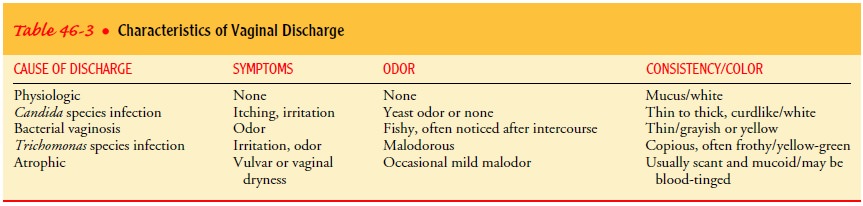

Vaginal

discharge, which may be normal or may result from vaginitis, may be present.

Discharge caused by bacteria (bacterial vaginosis) usually appears gray and

purulent. Discharge caused by Trichomonas

species infection is usually frothy, copious, and mal-odorous. Discharge

caused by Candida species infection

is usu-ally thick and white-yellow and has a cottage-cheese appearance. Table

46-3 summarizes the characteristics of vaginal discharge found in different

conditions.

The

vagina is inspected as the examiner withdraws the specu-lum. It is smooth in

young girls and thickens after puberty, with many rugae (folds) and redundancy

in the epithelium. In meno-pausal women, the vagina thins and has fewer rugae

because of decreased estrogen.

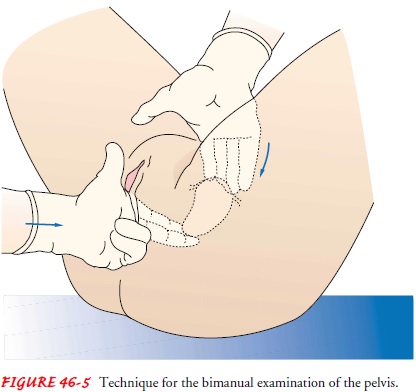

Bimanual Palpation

To

complete the pelvic examination, the examiner performs a bi-manual examination

from a standing position. The examination is performed with the forefinger and

middle finger of the gloved and lubricated hand. These fingers are placed in

the vaginal ori-fice, while the other fingers are held tightly out of the way,

with the thumb completely adducted. The fingers are advanced verti-cally along

the vaginal canal, and the vaginal wall is palpated. Any firm part of the

vaginal wall may represent old scar tissue from childbirth trauma but may also

require further evaluation.

CERVICAL PALPATION

The

cervix is palpated and assessed for its consistency, mobility, size, and

position. The normal cervix is uniformly firm but not hard. Softening of the

cervix is a finding in early pregnancy. Hardness and immobility of the cervix

may reflect invasion by a neoplasm. Pain on gentle movement of the cervix is

called a pos-itive chandelier sign

or positive cervical motion tenderness (recorded as +CMT)

and usually indicates a pelvic infection.

UTERINE PALPATION

To

palpate the uterus, the examiner places the opposite hand on the abdominal wall

halfway between the umbilicus and the pubis and presses firmly toward the

vagina (Fig. 46-5). Movement of the abdominal wall causes the body of the

uterus to descend, and the pear-shaped organ becomes freely movable between the

ab-dominal examining hand and the fingers of the pelvic examining hand. Uterine

size, mobility, and contour can be estimated through palpation. Fixation of the

uterus in the pelvis may be a sign of endometriosis

or malignancy.

The body of the uterus is normally twice the diameter and twice the length of the cervix, curving anteriorly toward the abdominal wall. Some women have a retroverted or retroflexed uterus, which tips posteriorly toward the sacrum, whereas others have a uterus that is neither anterior nor posterior but is midline.

ADNEXAL PALPATION

Next,

the right and left adnexal areas are palpated to evaluate the fallopian tubes

and ovaries. The fingers of the hand examining the pelvis are moved first to

one side, then to the other, while the hand palpating the abdominal area is

moved correspondingly to either side of the abdomen and downward. The adnexa

(ovaries and fallopian tubes) are trapped between the two hands and pal-pated

for an obvious mass, tenderness, and mobility. Commonly, the ovaries are

slightly tender, and the patient is informed that slight discomfort on

palpation is normal.

VAGINAL AND RECTAL PALPATION

Bimanual palpation of the vagina and cul-de-sac is accomplished by placing the index finger in the vagina and the middle finger in the rectum. To prevent cross-contamination between the vaginal and rectal orifices, the examiner puts on new gloves. A gentle movement of these fingers toward each other compresses the pos-terior vaginal wall and the anterior rectal wall and assists the ex-aminer in identifying the integrity of these structures. During this procedure, the patient may sense an urge to defecate. The nurse assures the patient that this is unlikely to occur. Ongoing expla-nations are provided to reassure and educate the patient about the procedure.

Gerontologic Considerations

Yearly

examinations can help prevent problems of the repro-ductive tract in aging

women. Some older women do not have regular gynecologic examinations. If a

woman delivered her chil-dren at home, she may never have had a pelvic

examination. Some regard it as an embarrassing and unpleasant procedure. An

im-portant role of the nurse is to encourage an annual gynecologic examination

for all women. The nurse can make the examina-tion a time for education and

reassurance rather than a time of embarrassment.

Perineal

pruritus is common in elderly women and should be evaluated because it may

indicate a disease process (diabetes or malignancy). It may also indicate

vulvar dystrophy, a thickened or whitish discoloration of tissue that needs

biopsy to rule out ab-normal cells. Topical cortisone and hormone creams may be

pre-scribed for symptomatic relief.

With

relaxing pelvic musculature, uterine prolapse and re-laxation of the vaginal

walls can occur. Appropriate evaluation and surgical repair can provide relief

if the patient is a candidate for surgery. After surgery, the patient needs to

know that tissue repair and healing may require additional time. Pessaries

(latex devices that provide support) are often used if surgery is

con-traindicated or before surgery to see if surgery can be avoided. They are

fitted by a health care provider and may reduce dis-comfort and pressure. Use

of a pessary requires the patient to have routine gynecologic examinations to

monitor for irritation or infection.

Related Topics