Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Chest and Lower Respiratory Tract Disorders

Aspiration

Aspiration

Aspiration

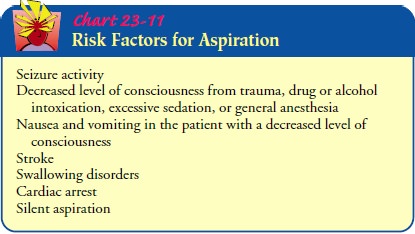

of stomach contents into the lungs is a serious com-plication that may cause

pneumonia and result in the following clinical picture: tachycardia, dyspnea,

central cyanosis, hyperten-sion, hypotension, and finally death. It can occur

when the pro-tective airway reflexes are decreased or absent from a variety of

factors (Chart 23-11).

Pathophysiology

The

primary factors responsible for death and complications after aspiration of

gastric contents are the volume and character of the aspirated gastric

contents. For example, a small, localized aspira-tion from regurgitation can

cause pneumonia and acute respira-tory distress; a massive aspiration is

usually fatal.

A full stomach contains solid particles of food. If these are as-pirated, the problem then becomes one of mechanical blockage of the airways and secondary infection. During periods of fasting, the stomach contains acidic gastric juice, which, if aspirated, may be very destructive to the alveoli and capillaries. Fecal contami-nation (more likely seen in intestinal obstruction) increases the likelihood of death because the endotoxins produced by intesti-nal organisms may be absorbed systemically, or the thick pro-teinaceous material found in the intestinal contents may obstruct the airway, leading to atelectasis and secondary bacterial invasion.

Aspiration

pneumonitis may develop from aspiration of sub-stances with a pH of less than

2.5 and a volume of gastric aspirate greater than 0.3 mL per kilogram of body

weight (20 to 25 mL in adults) (Marik, 2001). Aspiration of gastric contents causes

a chemical burn of the tracheobronchial tree and pulmonary parenchyma (Marik,

2001). An inflammatory response occurs. This results in the destruction of

alveolar–capillary endothelial cells, with a consequent outpouring of

protein-rich fluids into the interstitial and intra-alveolar spaces. As a

result, surfactant is lost, which in turn causes the airways to close and the

alveoli to col-lapse. Finally, the impaired exchange of oxygen and carbon

diox-ide causes respiratory failure.

Aspiration

pneumonia develops following inhalation of colo-nized oropharyngeal material.

The pathologic process involves an acute inflammatory response to bacteria and

bacterial products. Most commonly, the bacteriologic findings include

gram-positive cocci, gram-negative rods, and occasionally anaerobic bacteria

(Marik, 2001).

Prevention

Prevention

is the primary goal when caring for patients at risk for aspiration.

COMPENSATING FOR ABSENT REFLEXES

Aspiration

is likely to occur if the patient cannot adequately co-ordinate protective

glottic, laryngeal, and cough reflexes. This hazard is increased if the patient

has a distended abdomen, is in a supine position, has the upper extremities

immobilized by in-travenous infusions or hand restraints, receives local

anesthetics to the oropharyngeal or laryngeal area for diagnostic procedures,

has been sedated, or has had long-term intubation.

When

vomiting, a person can normally protect the airway by sitting up or turning on

the side and coordinating breathing, coughing, gag, and glottic reflexes. If

these reflexes are active, an oral airway should not be inserted. If an airway

is in place, it should be pulled out the moment the patient gags so as not to

stimulate the pharyngeal gag reflex and promote vomiting and as-piration.

Suctioning of oral secretions with a catheter should be performed with minimal

pharyngeal stimulation.

ASSESSING FEEDING TUBE PLACEMENT

Even when the patient is intubated, aspiration may occur even with a nasogastric tube in place. This aspiration may result in nosocomial pneumonia. Assessment of tube placement is key to prevent aspiration. The best method for determining tube place-ment is via an x-ray. There are other nonradiologic methods that have been studied. Observation of the aspirate and testing of its pH are the most reliable. Gastric fluid may be grassy green, brown, clear, or colorless. An aspirate from the lungs may be off-white or tan mucus. Pleural fluid is watery and usually straw-colored (Metheny & Titler, 2001). Gastric pH values are typically lower or more acidic that that of the intestinal or respiratory tract. Gastric pH is usually between 1 and 5, while intestinal or respi-ratory pH is 7 or higher (Metheny & Titler, 2001). There are dif-ferences in assessing tube placement with continuous versus intermittent feedings. For intermittent feedings with small-bore tubes, observation of aspirated contents and pH evaluation should be performed. For continuous feedings, the pH method is not clinically useful due to the infused formula (Metheny & Titler, 2001).

The

patient who is receiving continuous or timed-interval tube feedings must be

positioned properly. The patient receiving a con-tinuous infusion is given

small volumes under low pressure in an upright position, which helps to prevent

aspiration. Patients re-ceiving tube feedings at timed intervals are maintained

in an up-right position during the feeding and for a minimum of 30 minutes

afterward to allow the stomach to empty partially. Tube feedings must be given

only when it is certain that the feeding tube is posi-tioned correctly in the

stomach. Many patients today receive en-teral feeding directly into the

duodenum through a small-bore flexible feeding tube or surgically implanted

tube. Feedings are given slowly and regulated by a feeding pump. Correct

placement is confirmed by chest x-ray.

IDENTIFYING DELAYED STOMACH EMPTYING

A

full stomach may cause aspiration because of increased intra-gastric or

extragastric pressure. The following clinical situations cause a delayed

emptying time of the stomach and may con-tribute to aspiration: intestinal

obstruction; increased gastric secretions in gastroesophageal reflex disease;

increased gastric se-cretions during anxiety, stress, or pain; or abdominal distention

because of ileus, ascites, peritonitis, use of opioids and sedatives, severe

illness, or vaginal delivery.

When

a feeding tube is present, contents are aspirated, usually every 4 hours, to

determine the amount of the last feeding left in the stomach (residual volume).

If more than 50 mL is aspirated, there may be a problem with delayed emptying,

and the next feeding should be delayed or the continuous feeding stopped for a

period of time.

MANAGING EFFECTS OF PROLONGED INTUBATION

Prolonged

endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy can depress the laryngeal and glottic

reflexes because of disuse. Patients with prolonged tracheostomies are

encouraged to phonate and exer-cise their laryngeal muscles. For patients who

have had long-term intubation or tracheostomies, it may be helpful to have a

reha-bilitation therapist experienced in speech and swallowing disor-ders work

with the patient to assess the swallowing reflex.

Related Topics