Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Coronary Vascular Disorders

Angina Pectoris - Coronary Artery Disease

ANGINA PECTORIS

Angina

pectoris is a clinical syndrome usually characterized by episodes or paroxysms

of pain or pressure in the anterior chest. The cause is usually insufficient

coronary blood flow. The insufficient flow results in a decreased oxygen supply

to meet an increased myocardial demand for oxygen in response to physical

exertion or emotional stress. In other words, the need for oxygen exceeds the

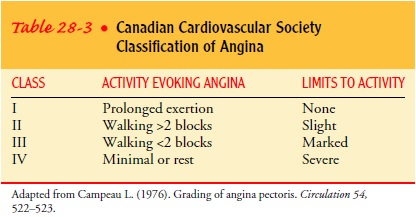

supply. The severity of angina is based on the precipitating activity and its

effect on the activities of daily living (Table 28-3).

Pathophysiology

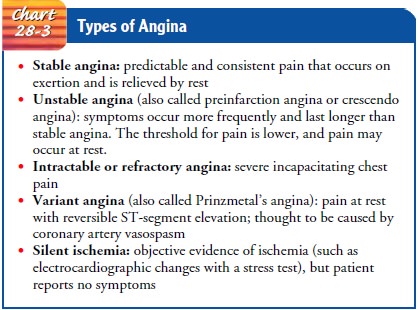

Angina is usually caused by atherosclerotic disease. Almost in-variably, angina is associated with a significant obstruction of a major coronary artery. The characteristics of the various types of angina are listed in Chart 28-3.

Identifying angina requires ob-taining a thorough history. Effective treatment

begins with re-ducing the demands placed on the heart and teaching the patient

about the condition. Several factors are associated with typical anginal pain:

·

Physical exertion, which can

precipitate an attack by in-creasing myocardial oxygen demand

·

Exposure to cold, which can cause

vasoconstriction and an elevated blood pressure, with increased oxygen demand

·

Eating a heavy meal, which increases

the blood flow to the mesenteric area for digestion, thereby reducing the blood

supply available to the heart muscle (In a severely com-promised heart,

shunting of blood for digestion can be suf-ficient to induce anginal pain.)

· Stress or any emotion-provoking situation, causing the re-lease of adrenaline and increasing blood pressure, which may accelerate the heart rate and increase the myocardial workload Atypical angina is not associated with the listed factors. It may occur at rest.

Clinical Manifestations

Ischemia

of the heart muscle may produce pain or other symp-toms, varying in severity

from a feeling of indigestion to a choking or heavy sensation in the upper

chest that ranges from discomfort to agonizing pain accompanied by severe

apprehension and a feeling of impending death. The pain is often felt deep in

the chest behind the upper or middle third of the sternum (retrosternal area). Typically,

the pain or discomfort is poorly localized and may radiate to the neck, jaw,

shoulders, and inner aspects of the upper arms, usually the left arm. The

patient often feels tight-ness or a heavy, choking, or strangling sensation

that has a vise-like, insistent quality. The patient with diabetes mellitus may

not have severe pain with angina because the neuropathy that ac-companies

diabetes can interfere with neuroreceptors, dulling the patient’s perception of

pain.

A

feeling of weakness or numbness in the arms, wrists, and hands may accompany

the pain, as may shortness of breath, pallor, diaphoresis, dizziness or

lightheadedness, and nausea and vomiting. These symptoms may also appear alone

and still rep-resent myocardial ischemia. When these symptoms appear alone,

they are called angina-like symptoms. Anxiety may accompany angina. An

important characteristic of angina is that it abates or subsides with rest or

nitroglycerin.

Gerontologic Considerations

The

elderly person with angina may not exhibit the typical pain profile because of

the diminished responses of neurotransmitters that occur in the aging process.

Often, the presenting symptom in the elderly is dyspnea. If they do have pain,

it is atypical pain that radiates to both arms rather than just the left arm.

Sometimes, there are no symptoms (“silent” CAD), making recognition and

diagnosis a clinical challenge. Elderly patients should be encour-aged to

recognize their chest pain–like symptom (eg, weakness) as an indication that

they should rest or take prescribed medica-tions. Noninvasive stress testing

used to diagnose CAD may not be as useful in elderly patients because of other

conditions (eg, peripheral vascular disease, arthritis, degenerative disk

disease, physical disability, foot problems) that limit the patient’s ability

to exercise.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

The

diagnosis of angina is often made by evaluating the clinical manifestations of

ischemia and the patient’s history. A 12-lead ECG and blood laboratory values

help in making the diagnosis. The patient may undergo an exercise or

pharmacologic stress test in which the heart is monitored by ECG,

echocardiogram, or both. The patient may also be referred for an

echocardiogram, nuclear scan, or invasive procedures (cardiac catheterization

and coronary artery angiography).

CAD

is believed to result from inflammation of the arterial endothelium. C-reactive

protein (CRP) is a marker for inflam-mation of vascular endothelium. High blood

levels of CRP have been associated with increased coronary artery calcification

and risk of an acute cardiovascular event (eg, MI) in seemingly healthy

in-dividuals (Ridker et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2002). There is inter-est in

using CRP blood levels as an additional risk factor for cardiovascular disease

in clinical use and research, but the clini-cal value of CRP levels has not

been fully established. The ability of CRP to predict cardiovascular disease

when adjusted for other risk factors, how CRP levels can guide patient

management, and if patient outcomes improve when using CRP levels must be

es-tablished before CRP levels are used routinely for patient care (Mosca,

2002).

An

elevated blood level of homocysteine, an amino acid, has also been proposed as

an independent risk factor for cardio-vascular disease. However, studies have

not supported the relation-ship between mild to moderate elevations of

homocysteine and atherosclerosis (Homocysteine Studies Collaboration, 2002). No

study has yet shown that reducing homocysteine levels reduces the risk of CAD.

Medical Management

The

objectives of the medical management of angina are to de-crease the oxygen

demand of the myocardium and to increase the oxygen supply. Medically, these

objectives are met through phar-macologic therapy and control of risk factors.

Revascularization

procedures to restore the blood supply to the myocardium include percutaneous coronary interventional(PCI) procedures

(eg, percutaneous transluminal coronary

angioplasty [PTCA], intracoronary stents, and atherectomy),CABG, and

percutaneous transluminal myocardial revascular-ization (PTMR).

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Among

medications used to control angina are nitroglycerin, beta-adrenergic blocking

agents, calcium channel blockers, and antiplatelet agents.

Nitroglycerin.

Nitrates

remain the mainstay for treatment ofangina pectoris. A vasoactive agent,

nitroglycerin (Nitrostat, Nitrol, Nitrobid IV) is administered to reduce

myocardial oxygen consumption, which decreases ischemia and relieves pain.

Nitro-glycerin dilates primarily the veins and, in higher doses, also dilates

the arteries. It helps to increase coronary blood flow by preventing

vasospasm and increasing perfusion through the col-lateral vessels.

Dilation

of the veins causes venous pooling of blood through-out the body. As a result,

less blood returns to the heart, and fill-ing pressure (preload) is reduced. If

the patient is hypovolemic (does not have adequate circulating blood volume),

the decrease in filling pressure can cause a significant decrease in cardiac

out-put and blood pressure.

Nitrates

in higher doses also relax the systemic arteriolar bed and lower blood pressure

(decreased afterload). Nitrates may in-crease blood flow to diseased coronary

arteries and through col-lateral coronary arteries, arteries that have been

underused until the body recognizes poorly perfused areas. These effects

decrease myo-cardial oxygen requirements and increase oxygen supply, bringing

about a more favorable balance between supply and demand.

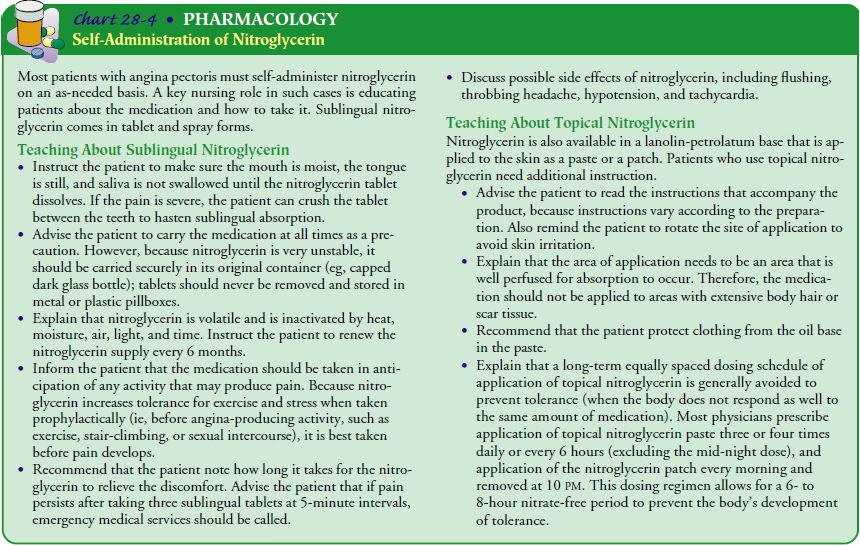

Nitroglycerin

may be given by several routes: sublingual tablet or spray, topical agent, and

intravenous administration. Sublingual nitroglycerin is generally placed under

the tongue or in the cheek (buccal pouch) and alleviates the pain of ischemia

within 3 min-utes. Topical nitroglycerin is also fast acting and is a

convenient way to administer the medication. Both routes are suitable for

pa-tients who self-administer the medication. Chart 28-4 provides more

information.

A

continuous or intermittent intravenous infusion of nitro-glycerin may be

administered to the hospitalized patient with re-curring signs and symptoms of

ischemia or after a revascularization procedure. The amount of nitroglycerin

administered is based on the patient’s symptoms while avoiding side effects

such as hy-potension. It usually is not given if the systolic blood pressure is

90 mm Hg or less. Generally, after the patient is symptom free, the

nitroglycerin may be switched to a topical preparation within 24 hours.

Beta-Adrenergic Blocking Agents.

Beta-blockers such as propran-olol (Inderal), metoprolol

(Lopressor, Toprol), and atenolol (Tenormin) appear to reduce myocardial oxygen

consumption by blocking the beta-adrenergic sympathetic stimulation to the

heart. The result is a reduction in heart rate, slowed conduction of an impulse

through the heart, decreased blood pressure, and reduced myocardial contractility (force of contraction)

that es-tablishes a more favorable balance between myocardial oxygen needs

(demands) and the amount of oxygen available (supply). This helps to control

chest pain and delays the onset of ischemia during work or exercise.

Beta-blockers reduce the incidence of recurrent angina, infarction, and cardiac

mortality. The dose can be titrated to achieve a resting heart rate of 50 to 60

beats per minute.

Cardiac side effects and possible contraindications include hy-potension, bradycardia, advanced atrioventricular block, and de-compensated heart failure. If a beta-blocker is given intravenously for an acute cardiac event, the ECG, blood pressure, and heart rate are monitored closely after the medication has been administered. Because some beta-blockers also affect the beta-adrenergic recep-tors in the bronchioles, causing bronchoconstriction, they are con-traindicated in patients with significant pulmonary constrictive diseases, such as asthma. Other side effects include worsening of hyperlipidemia, depression, fatigue, decreased libido, and mask-ing of symptoms of hypoglycemia. Patients taking beta-blockers are cautioned not to stop taking them abruptly, because angina may worsen and MI may develop. Beta-blocker therapy needs to be decreased gradually over several days before discontinuing it. Patients with diabetes who take beta-blockers are instructed to as-sess their blood glucose levels more often and to observe for signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia.

Calcium Channel Blocking Agents.

Calcium channel blockers(calcium ion antagonists) have different

effects. Some decrease sinoatrial node automaticity and atrioventricular node

conduc-tion, resulting in a slower heart rate and a decrease in the strength of

the heart muscle contraction (negative inotropic effect). These effects

decrease the workload of the heart. Calcium channel block-ers also relax the

blood vessels, causing a decrease in blood pres-sure and an increase in

coronary artery perfusion. Calcium channel blockers increase myocardial oxygen

supply by dilating the smooth muscle wall of the coronary arterioles; they

decrease myocardial oxygen demand by reducing systemic arterial pressure and

the workload of the left ventricle.

The

calcium channel blockers most commonly used are am-lodipine (Norvasc),

verapamil (Calan, Isoptin, Verelan), and dilti-azem (Cardizem, Dilacor,

Tiazac). They may be used by patients who cannot take beta-blockers, who

develop significant side effects from beta-blockers or nitrates, or who still

have pain despite beta-blocker and nitroglycerin therapy. Calcium channel

blockers are used to prevent and treat vasospasm, which commonly occurs after

an invasive interventional procedure. Use of short-acting nifedi-pine

(Procardia) was found to be poorly tolerated and to increase the risk of MI in

patients with hypertension and the risk of death in patients with acute coronary syndrome (Braunwald et

al., 2000; Furberg et al., 1996; Ryan et al., 1999).

First-generation

calcium channel blockers should be avoided or used with great caution in people

with heart failure, because they decrease myocardial contractility. Amlodipine

(Norvasc) and felodipine (Plendil) are the calcium channel blockers of choice

for patients with heart failure. Hypotension may occur after the intra-venous

administration of any of the calcium channel blockers. Other side effects that

may occur include atrioventricular blocks, bradycardia, constipation, and

gastric distress.

Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Medications.

Antiplatelet med-ications are administered to prevent platelet

aggregation, which impedes blood flow.

Aspirin.

Aspirin

prevents platelet activation and reduces the in-cidence of MI and death in

patients with CAD. A 160- to 325-mg dose of aspirin should be given to the

patient with angina as soon as the diagnosis is made (eg, in the emergency room

or physician’s office) and then continued with 81 to 325 mg daily. Although it

may be one of the most important medications in the treatment of CAD, aspirin

may be overlooked because of its low cost and common use. Patients should be

advised to continue aspirin even if concurrently taking nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or other analgesics. Because aspirin may cause

gastro-intestinal upset and bleeding, treatment of Helicobacter pylori and the use of H2-blockers (eg, cimetidine

[Tagamet], famotidine [My-lanta AR, Pepcid], ranitidine [Zantac]) or misoprostol

(Cytotec) should be considered to allow continued aspirin therapy.

Clopidogrel and Ticlopidine.

Clopidogrel (Plavix) or ticlopidine(Ticlid) is given to patients

who are allergic to aspirin or given in addition to aspirin in patients at high

risk for MI. Unlike aspirin, these medications take a few days to achieve their

antiplatelet effect. They also cause gastrointestinal upset, including nausea,

vomiting, and diarrhea, and they decrease the neutrophil level.

Heparin.

Unfractionated

heparin prevents the formation of newblood clots. Use of heparin alone in

treating patients with unstable angina reduces the occurrence of MI. If the

patient’s signs and symptoms indicate a significant risk for a cardiac event,

the patient is hospitalized and may be given an intravenous bolus of heparin

and started on a continuous infusion or given an intravenous bolus every 4 to 6

hours. The amount of heparin administered is based on the results of the

activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT). Heparin therapy is usually considered

therapeutic when the aPTT is 1.5 to 2 times the normal aPTT value.

A

subcutaneous injection of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH; enoxaparin

[Lovenox] or dalteparin [Fragmin]) may be used instead of intravenous

unfractionated heparin to treat patients with unstable angina or non–ST-segment

elevation MIs. LMWH provides more effective and stable anticoagulation,

potentially reducing the risk of rebound ischemic events, and it eliminates the

need to monitor aPTT results (Cohen, 2001). LMWH may be beneficial before and

during PCIs and for ST-segment elevation MIs.

Because

unfractionated heparin and LMWH increase the risk of bleeding, the patient is

monitored for signs and symptoms of external and internal bleeding, such as low

blood pressure, an in-creased heart rate, and a decrease in serum hemoglobin

and hematocrit values. The patient receiving heparin is placed on bleeding

precautions, which include:

·

Applying pressure to the site of any

needle puncture for a longer time than usual

·

Avoiding intramuscular injections

·

Avoiding tissue injury and bruising

from trauma or use of constrictive devices (eg, continuous use of an automatic

blood pressure cuff)

A

decrease in platelet count or skin lesions at heparin injection sites may

indicate heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), an antibody-mediated reaction

to heparin that may result in throm-bosis (Hirsh et al., 2001). Patients who

have received heparin within the past 3 months and those who have been

receiving un-fractionated heparin for 5 to 15 days are at high risk for HIT.

GPIIb/IIIa Agents.

Intravenous

GPIIb/IIIa agents (abciximab[ReoPro], tirofiban [Aggrastat], eptifibatide

[Integrelin]) are indi-cated for hospitalized patients with unstable angina and

as adjunct therapy for PCI. These agents prevent platelet aggregation by

blocking the GPIIb/IIIa receptors on the platelet, preventing adhesion of

fibrinogen and other factors that crosslink platelets to each other and thereby

allow platelets to form a thrombus (clot). As with heparin, bleeding is the

major side effect, and bleeding pre-cautions should be initiated.

Oxygen Administration.

Oxygen therapy is usually initiated atthe onset of chest pain in

an attempt to increase the amount of oxygen delivered to the myocardium and to

decrease pain. Oxy-gen inhaled directly increases the amount of oxygen in the

blood. The therapeutic effectiveness of oxygen is determined by observ-ing the

rate and rhythm of respirations. Blood oxygen saturation is monitored by pulse

oximetry; the normal oxygen saturation (SpO2) level is greater than 93%. Studies are being conducted to assess

the use of oxygen in patients without respiratory distress and its effect on

outcome.

ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES

Researchers

have reported significant improvement in the exer-cise endurance of patients

with angina who were treated with acupuncture as well as with an intravenous

infusion of a combina-tion of ginseng (Panax

quinquefolium), astragalus (Astragalus

mem-branaceus), and angelica (Angelica

sinensis) (Ballegaard et al., 1991;Reichter et al., 1991). Coenzyme Q10 was

advocated for prevent-ing the occurrence and progression of heart failure

(Khatta et al., 2000). However, there have not been large, randomized,

placebo-controlled studies that identify the direct beneficial effect from these

therapies.

Related Topics