Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Anesthesia for Otorhinolaryngologic Surgery

Anesthesia for Maxillofacial Reconstruction & Orthognathic Surgery

MAXILLOFACIAL RECONSTRUCTION & ORTHOGNATHIC SURGERY

Maxillofacial reconstruction is often required to correct the effects of

trauma (eg, LeFort fractures) or developmental malformations, for radical

cancer surgeries (eg, maxillectomy or mandibulectomy), or for obstructive sleep

apnea. Orthognathic pro-cedures (eg, LeFort osteotomies, mandibular

oste-otomies) for skeletal malocclusion share many of the same surgical and

anesthetic techniques.

Preoperative Considerations

Patients undergoing maxillofacial

reconstruc-tion or orthognathic surgical procedures oftenpose airway

challenges. Particular attention should be focused on jaw opening, mask fit,

neck mobility, micrognathia, retrognathia, maxillary protrusion (overbite),

macroglossia, dental pathology, nasal patency, and the existence of any

intraoral lesions or debris. If there are any anticipated signs of prob-lems

with mask ventilation or tracheal intubation, the airway should be secured

prior to induction of general anesthesia. This may involve fiberoptic nasal

intubation, fiberoptic oral intubation, or tracheos-tomy with local anesthesia

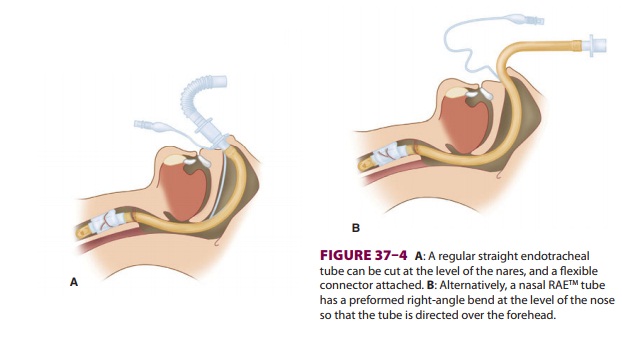

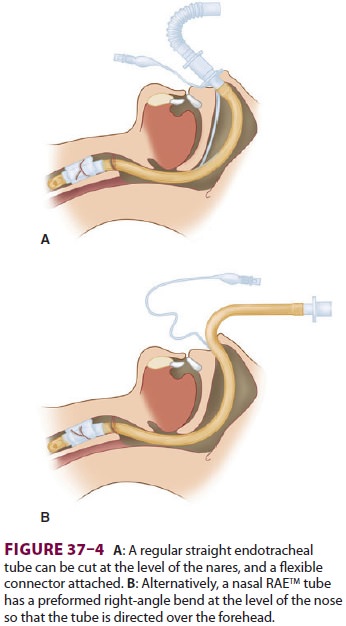

facilitated with cautious sedation. Nasal intubation with a straight tube with

a flexible angle connector (Figure 37–4A)

or a pre-formed nasal RAE® ( Figure 37–4B)

tube is usually preferred in dental and oral surgery. The endotra-cheal tube

can then be directed cephalad over the patient’s forehead. With any nasal

intubation, care should be taken to prevent the endotracheal tube from putting

pressure on the tissues of the nasal opening, as this situation may result in

local tissue pressure necrosis in the setting of a lengthy surgical procedure.

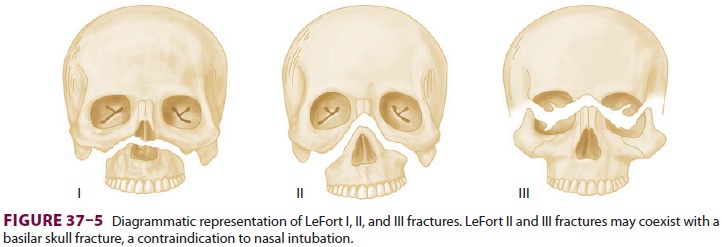

Nasal intubation should be considered with caution in LeFort II and III

fractures because of the possibility of a coexisting basilar skull fracture (Figure

37–5).

Intraoperative Management

Maxillofacial reconstructive and orthognathic sur-geries can be lengthy and associated with substantial blood loss. An oropharyngeal (“throat”) pack is often placed to minimize the amount of blood and other debris reaching the larynx and trachea. Strategies to minimize bleeding include a slight head-up posi-tion, controlled hypotension, and local infiltration with epinephrine solutions. Because the patient’s arms are typically tucked at the side, two intrave-nous lines may be established prior to surgery. An arterial line may be placed. If head-up tilt is utilized, it is important that the arterial blood pressure trans-ducer be zeroed at the level of the brain (external auditory meatus) in order to most accurately deter-mine cerebral perfusion pressure. In addition, the anesthesia provider must be alert to the increased risk of venous air embolism in the setting of head-up tilt.

Because of the proximity of the airway to the surgical field, the anesthesiologist’s location is more remote than usual. This increases the likelihood of serious intraoperative airway problems, such as endotracheal tube kinking, disconnection, or perfo-ration by a surgical instrument. Monitoring of end-tidal CO2, peak inspiratory pressures, and breath sounds via an esophageal stethoscope assume greater importance in such cases. If the operative procedure is near the airway, the use of electocau-tery or laser increases the risk of fire. At the end of surgery, the oropharyngeal pack must be removed and the pharynx suctioned. Bloody debris is typi-cally found during initial suctioning, but shoulddiminish with repeat efforts. If there is a pos-sibility of postoperative tissue edema involving structures that could potentially obstruct the airway (eg, tongue, pharynx), the patient should be carefully observed or left intubated. In such uncer-tain situations, extubation may be performed over an endotracheal tube exchanger (Cook Airway Exchange Catheter with Rapi-Fit® Adapter, Cook Medical), which can facilitate reintubation and pro-vide oxygenation in the setting of immediate postextubation respiratory obstruction. In addition, the operating team should be prepared for emer-gent tracheotomy or cricothyrotomy. Otherwise, extubation can be attempted once the patient is fully awake and there are no signs of continued bleeding. Patients with intermaxillary fixation (eg, maxillomandibular wiring) must have suction and appropriate wire cutting tools continuously at the bedside in case of vomiting or other airway emergencies. Extubating a patient whose jaws are wired shut and whose oropharyngeal pack has not been removed can lead to life threatening airway obstruction.

Related Topics