Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Anesthesia for Genitourinary Surgery

Anesthesia for Cystoscopy

CYSTOSCOPY

Preoperative Considerations

Cystoscopy is the most commonly performed uro-logical procedure,

and indications for this investi-gative or therapeutic operation include

hematuria, recurrent urinary infections, renal calculi, and urinary

obstruction. Bladder biopsies, retrograde pyelograms, transurethral resection

of bladder tumors, extraction or laser lithotripsy of renal stones, and

placement or manipulation of ureteral catheters (stents) are also commonly

performed through the cystoscope.

Anesthetic management varies with the age and gender of the

patient and the purpose of the procedure. General anesthesia is usually

necessary for children. Viscous lidocaine topical anesthesia with or without

sedation is satisfactory for diag-nostic studies in most women because of the

short urethra. Operative cystoscopies involving biopsies, cauterization, or

manipulation of ureteral catheters require regional or general anesthesia. Many

men prefer regional or general anesthesia even for diag-nostic cystoscopy.

Intraoperative Considerations

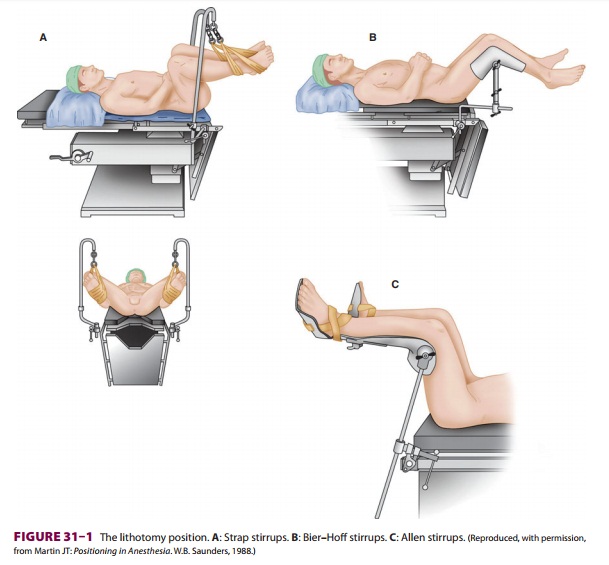

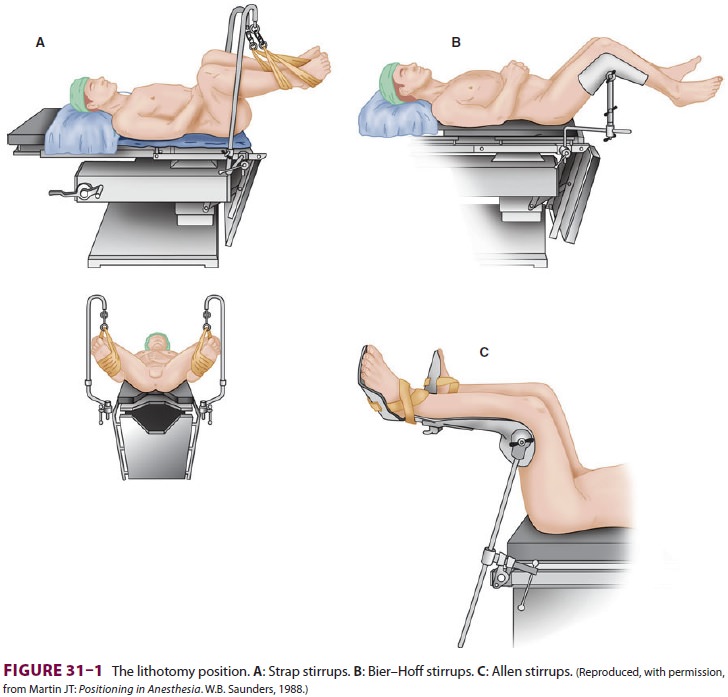

A. Lithotomy Position

Next to the supine position, the

lithotomy position is the most commonly used positionfor patients undergoing

urological and gynecologi-cal procedures. Failure to properly position and pad

the patient can result in pressure sores, nerve inju-ries, or compartment

syndromes. Two people are needed to safely move the patient’s legs simultane-ously

up into, or down from, the lithotomy position. Straps around the ankles or

special holders support the legs in lithotomy position ( Figure 31–1).

The leg supports should be padded wherever there is leg or foot contact, and

straps must not impede circula-tion. When the patient’s arms are tucked to the

side, caution must be exercised to prevent the fingers from being caught

between the mid and lower sec-tions of the operating room table when the lower

section is lowered and raised—many clinicians com-pletely encase the patient’s

hands and fingers with

protective padding to minimize this

risk. Injury to the tibial (common peroneal) nerve, resulting in loss of

dorsiflexion of the foot, may result if the lateral knee rests against the

strap support. If the legs are allowed to rest on medially placed strap

supports, compression of the saphenous nerve can result in numbness along the

medial calf. Excessive flexion of the thigh against the groin can injure the

obturator and, less commonly, the femoral nerves. Extreme flexion at the thigh

can also stretch the sciatic nerve. The most common nerve injuries directly

associated with the lithotomy position involve the lumbosacral plexus. Brachial

plexus injuries can likewise occur if the upper extremities are inappropriately

positioned (eg, hyperextension at the axilla). Compartment syndrome of the

lower extremities with rhabdomy-olysis has been reported with prolonged time in

the lithotomy position, after which lower extremity nerve damage is also more

likely.

The lithotomy position is associated

with major physiological alterations. Functionalresidual capacity decreases, predisposing patientsto

atelectasis and hypoxia. This effect is amplified by steep Trendelenburg

positioning (>30°), which is commonly utilized in

combination with the lithot-omy position. Elevation of the legs drains blood

into the central circulation acutely and may thereby exacerbate congestive

heart failure (or treat a rela-tive hypovolemia). Mean blood pressure and

cardiac output may increase. Conversely, rapid lowering of the legs from the

lithotomy or Trendelenburg posi-tion acutely decreases venous return and can

result in hypotension. Vasodilation from either general or regional anesthesia

potentiates the hypotension in this situation, and for this reason, blood

pressure measurement should be taken immediately after the legs are lowered.

B. Choice of Anesthesia

General

anesthesia—Many patients

are appre-hensive about the procedure and prefer to be asleep. However, any

anesthetic technique suitable for out patients may be utilized. Because of the

short duration (15–20 min) and outpatient settingof

most cystoscopies, general anesthesia is often chosen, commonly employing a

laryngeal mask air-way. Oxygen saturation should be closely monitored when

obese or elderly patients, or those with mar-ginal pulmonary reserve, are

placed in the lithotomy or Trendelenburg position.

2.

Regional anesthesia—Both

epidural andspinal blockade provide satisfactory anesthesia for cystoscopy. However, when regional

anesthesia is chosen most anesthesiologists prefer spinal anesthesia because

onset of satisfactory sen-sory blockade may require 15–20 min for epidural

anesthesia compared with 5 min or less for spinal anesthesia. Some clinicians

believe that the sen-sory level following injection of a hyperbaric spi-nal

anesthetic solution should be well established (“fixed”) before the patient is

moved into the lithot-omy position; however, studies fail to demonstrate that

immediate elevation of the legs into lithotomy position following

administration of hyperbaric spinal anesthesia either increases the dermatomal

extent of anesthesia to a clinically significant de-gree or increases the

likelihood of severe hypoten-sion. A sensory level to T10 provides excellent

an-esthesia for essentially all cystoscopic procedures.

Related Topics