Chapter: Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases: Clostridium, Peptostreptococcus, Bacteroides, and Other Anaerobes

Anaerobic Infections

ANAEROBIC INFECTIONS

EPIDEMIOLOGY

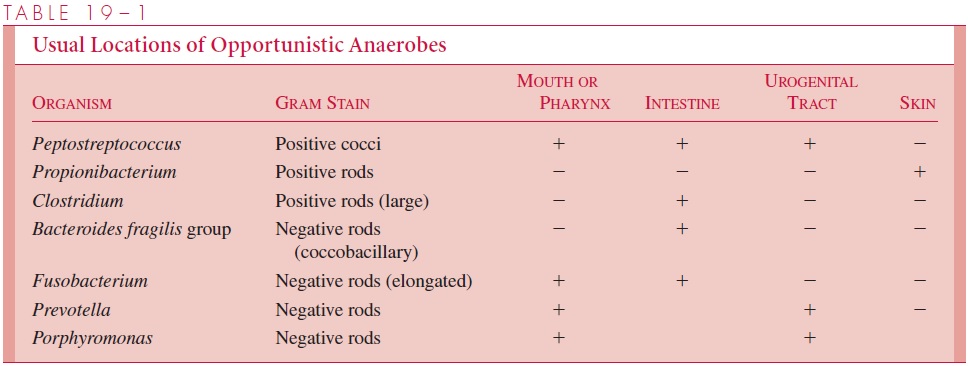

Despite our constant immersion in air, anaerobes are able to colonize the many oxygen-deficient or oxygen-free microenvironments of the body. Often these are created by the presence of facultative organisms whose growth reduces oxygen and decreases the local oxidation-reduction potential. Such sites include the sebaceous glands of the skin, the gingival crevices of the gums, the lymphoid tissue of the throat, and the lumina of the in-testinal and urogenital tracts. Except for infections with some environmental clostridia, anaerobic infections are almost always endogenous with the infective agent(s) derived from the patient’s normal flora. The specific anaerobes involved are linked to their preva-lence in the flora of the relevant sites as shown in Table 19 – 1. In addition to the presence of clostridia in the lower intestinal tract of humans and animals, their spores are widely distributed in the environment, particularly in soil exposed to animal excreta. The spores may contaminate any wound caused by a nonsterile object (eg, splinter, nail) or exposed directly to soil.

PATHOGENESIS

The anaerobic flora normally live in a harmless commensal relationship with the host. However, when displaced from their niche on the mucosal surface into normally sterile tissues these organisms may cause life-threatening infections. This can occur as the result of trauma (eg, gunshot, surgery), disease (eg, diverticulosis), or isolated events (eg, aspi-ration). Host factors such as malignancy or impaired blood supply increase the probabil-ity that the dislodged flora eventually produce an infection. The organisms involved are anaerobes normally found at the mucosal site adjacent to the infection. For example, B.fragilis, which is one of the most common species in the colonic flora, is the organismmost frequently isolated from intra-abdominal abscesses.

The relationship between normal flora and site of infection may be indirect. For ex-ample, aspiration pneumonia, lung abscess, and empyema typically involve anaerobes found in the oropharyngeal flora. The brain is not a particularly anaerobic environment, but brain abscess is most often caused by these same oropharyngeal anaerobes. This pre-sumably occurs by extension across the cribriform plate to the temporal lobe, the typical location of brain abscess. In contaminated open wounds, clostridia can come from the in-testinal flora or from spores surviving in the environment.

While gaining access to tissue sites provides the opportunity, additional virulence factors are needed for anaerobes to produce infection. Some anaerobic pathogens pro-duce disease even when present as a minor part of the displaced resident flora, and other common members of the normal flora rarely cause disease. Classical virulence factors such as toxins and capsules are known only for the toxigenic clostridia and B. fragilis, but a feature such as the ability to survive brief exposures to oxygenated en-vironments can also be viewed as a virulence factor. Anaerobes found in human infec-tions are far more likely to produce catalase and superoxide dismutase than their more docile counterparts of the normal flora. Exquisitely oxygen-sensitive anaerobes are seldom involved, probably because they are injured by even the small amounts of oxy-gen dissolved in tissue fluids.

A related feature is the ability of the bacteria to create and control a reduced microen-vironment, often with the apparent help of other bacteria. The great majority of anaerobic infections are mixed; that is, two or more anaerobes are present, often in combination with facultative bacteria such as Escherichia coli (Fig 19 – 1). In some cases the compo-nents of these mixtures are believed to synergize each other’s growth either by providing growth factors or by lowering the oxidation-reduction potential. These conditions may have other advantages such as the inhibition of oxygen-dependent leukocyte bactericidal functions under the anaerobic conditions in the lesion. Anaerobes that produce specific toxins have a pathogenesis all their own, which will be discussed in the sections devoted to individual species.

Related Topics