Chapter: Medicine and surgery: Gastrointestinal system

Abdominal hernias - Disorders of the abdominal wall

Disorders of the abdominal wall

Abdominal hernias

Definition

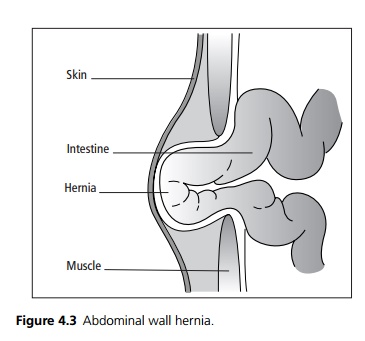

A hernia is the abnormal protrusion of an organ or tissue outside its normal body cavity or constraining sheath (see Fig. 4.3).

Incidence

85% occur in males, with a lifetime risk of 1 in 4 males, but less than 1 in 20 females. They increase with age.

Aetiology/pathophysiology

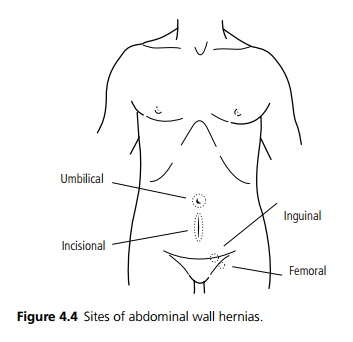

Congenital hernias exploit natural openings and weak-nesses. They may not become obvious until later in life and may be predisposed to by coughing straining, lifting, trauma or weak musculature. Examples of hernias include inguinal (direct and indirect), femoral, paraumbilical, umbilical and ventral hernias (see Fig. 4.4).

Of groin hernias, 60% are indirect inguinal, 25% are direct inguinal and 15% are femoral.

· Indirect inguinal hernias are a result of failure of obliteration of the processus vaginalis, a tube of peri toneum dragged down into the testes during the embryonic descent of the testes from the posterior abdominal wall. It is usually obliterated leaving the tunica vaginalis as a covering of the testes.

· Direct inguinal hernias occur as a result of weakness in the floor of the inguinal canal (through Hesselbach’s triangle which is formed inferiorly by the inguinal ligament, the inferior epigastric vessels laterally and the internal oblique muscle superiorly).

· Femoral hernias are due to a weakness of the femoral sheath, the top of which is the femoral ring bounded by the inguinal ligament anteriorly, the femoral vein laterally, the lacunar ligament medially and the superior ramus of the pubis posteriorly. Femoral hernias are particularly prone to incarceration or strangulation, as the angle of the canal makes the hernia difficult to reduce. Females have femoral hernias more often than males, but inguinal hernias are still the most common hernia in females (by 4 to 1).

· Incisional hernias occur at weakened areas caused by surgical incisions and muscle splitting. They occur in approximately 5% of postoperative patients, risk factors include infection, poor wound healing, coughing and surgical techniques.

Clinical features

Hernias may be completely asymptomatic, or present with a painless swelling, sudden pain at the moment of herniation and thereafter a dragging discomfort made worse by coughing, lifting, straining and defecation (which increase intra-abdominal pressure). Persistent or severe pain may be a sign of one of the complications of hernias, i.e. incarceration or strangulation. In most cases the hernia is not visible when the patient is lying supine. They are best examined standing and when the patient is coughing or straining. A bulge may be visible and a cough impulse is normally palpable. It can be difficult to distinguish the groin hernias.

· Indirect hernias once reduced can be controlled by pressure applied to the internal ring. This distinguishes indirect from direct hernias, which cannot be controlled, and where on reduction the edges of the defect may be palpable.

· An inguinal hernia passes above and medial to the pubic tubercle whereas a femoral hernia passes below and lateral.

Complications

Hernias are irreducible when the contents cannot be manipulated back into the abdomen. Irreducibility (incarceration) is more likely if the neck of the sac is narrow (e.g. femoral and paraumbilical hernias) or if the contents become distended. Obstruction of the intestine may occur causing abdominal pain, vomiting and distension.

Strangulation denotes compromise of the blood supply of the contents and significantly increases morbidity and mortality. The low-pressure venous system obstructs first, the resultant back pressure results in arterial insufficiency, ischaemia and ultimately infarction.

Investigations

These are rarely necessary to make the diagnosis, although imaging such as ultrasound is sometimes used.

Management

Surgical treatment is usually advised electively to reduce the risk of complications. However, longstanding, large hernias which are relatively asymptomatic may be treated conservatively, as they have a low risk of incarceration and strangulation. Treatment can be by open or laparoscopic repair. Direct hernias are reduced and the defect closed by suture or synthetic mesh. Indirect hernias are repaired by surgical removal of the herniation sac from the spermatic cord. If the internal ring is enlarged it is reduced surgically. For other hernias, the principle is to excise the sac and obliterate the opening either by suturing or mesh.

Prognosis

The recurrence rate of direct inguinal hernias is approximately 10%, but less with mesh techniques.

Related Topics